By Henry Jacob

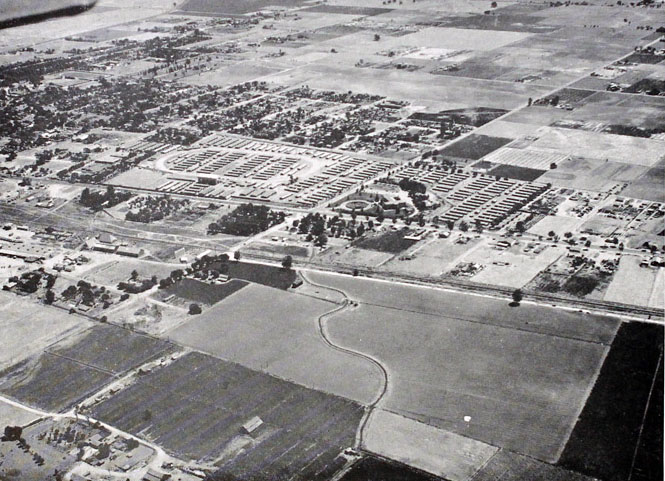

It is always hard to miss the chance to offer a farewell in person. Leftist organizer Walter Millsap faced this scenario on May 12, 1942. That night, Millsap arrived at the home of his best friend Keikichi Imamura in Pasadena, California. Even after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Millsap remained close to Keikichi, his wife Toshiko, and their child Keichi, all Japanese-Americans. Because their relationship transcended racial tensions, Millsap wanted to speak to the Imamuras before they traveled to Tulare Assembly Center, a temporary detention camp. But a broken stove had forced the family to eat out for dinner and miss Millsap. It is ironic that a faulty kitchen appliance denied the companions their proper adieus because the issue of food soon brought Millsap and Toshiko together. Indeed, writing missives became a source of sustenance for Toshiko in a carceral space of deprivation. Despite the paucity of nutritious rations, correspondence with Millsap – and his nurturing of her literary endeavors – helped her endure hardship.

Toshiko fell into a depression after her arrival in Tulare, primarily because of the unhealthy food dispensed in the cafeteria. Toshiko previously tended to a home garden and considered access to fresh produce a basic human right. For this reason, when she recalled the last time she passed by a seed store in California, her words evoke melancholy rather than nostalgia. She detailed seeing an array of “many plants – celery, tomatoe [sic], eggplant, radishes, cucumber, lettus [sic].” She also described the rainbow of the foods and flowers now unavailable to her. In a defeated tone, she questioned even the use of reminiscing: “what’s the use now… these are beyond me!” The exclamation point signals Toshiko’s despair that she no longer had a “freedom of choice.”[1] While free Americans planted Victory Gardens, Toshiko could not indulge her love of cultivation and wholesome crops. Surrounded by processed food – drained of all nutrition and color – Toshiko felt trapped within a culinary “cage.”[2] The excess of carbohydrates – “hominy. rice pudding. white bread.” – and dearth of freshness –fruits are “stewed” and vegetables “canned”– depleted her mind and body. [3] In fact, her prose adopted a similar degree of blandness. In one note, she simply copied menu items, too disheartened to complain further about the drab offerings. Other than her appositive phrase “cut just few inches square” to describe the beef, Toshiko left her language unprepared and undercooked, as it were.[4]

Notably, Millsap helped Toshiko emerge from her psychological nadir by cultivating her literary talents. Over months, he counseled Toshiko to channel her sorrow into fiction, doubling as a confidante and artistic agent. Allaying her fears about not yet mastering English, he assured Toshiko that the power of her sentiments would still surface. Millsap blended kindness with commands, challenging her to compose a piece “entirely by herself and without help.”[5] This suggestion prompted Toshiko to author her first short story, Heroic Japanese Mother, an autobiographical tale on the trials Japanese-American women faced during WWII. Although she may not have owned a garden in the internment camp, she did possess a vision. Rather than just copying menus, Toshiko crafted a piece of fiction. In doing so, she conquered her dispirited feelings over the grim surroundings through intellectual engagement.

Soon after finishing the first draft, Toshiko thanked Millsap for his encouragement. She even admitted that “I shall be the happiest woman in the world… if I ever be able to make a living with pen [sic.]”[6] After weeks of editing, Toshiko neared that dream, publishing Heroic Japanese Mother in Desert Magazine. Upon learning of this achievement, Millsap suggested to Toshiko that this news “should raise your morale considerably” and banish any lingering doubts.[7] This achievement represented Toshiko’s transcendence of the despair that plagued her early days of internment. Thus, it seems fitting that Toshiko joked to Millsap that “your help and encouragement was not altogether fruitless.”[8] Perhaps only a careless turn of phrase, the word “fruitless” implies that the actual fruit her body had craved transformed into a metaphorical fruit, borne of creative labor.A couple of years after releasing Heroic Japanese Mother, Toshiko and her family were finally released from their imprisonment. Although Toshiko certainly welcomed the freedom, she “had no time to write” and live by her pen.[9] Tasked to “‘keep the pot boiling’” for her household, she could not reflect on her condition as a Japanese-American woman.[10] Unfortunately, the surviving correspondence between the Imamuras and Millsap ended on January 5, 1946, providing no indication whether they reunited or if Toshiko pursued her literary ambitions. One can only hope that their abrupt 1942 parting was not the last and that Toshiko could, as she expressed soon before leaving Arizona, “come back to California and to work with you” – Millsap, her editor and friend, the man who nourished her imagination when her body starved.[11]

Author Bio: Henry Jacob is a recent Yale graduate and a current Henry Fellow at Cambridge pursuing an M.Phil. in World History. His scholarship focuses on Anglo-American designs for interoceanic transit in the tropic and arctic regions from the 19th century to the present.

Bibliography

Millsap, Walter, Keikichi Akana Imamura Family Papers. Western Americana Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut.

Imamura, Toshiko. “Heroic Japanese Mother” The Desert Magazine, November 1942.

Endnotes

[1] Toshiko Imamura to Marie Garth, May 5, 1942, box 1, Walter Millsap and Keikichi Akana Imamura Family Papers. Page 1.

[2] Toshiko Imamura to Marie Garth, May 27, 1942, box 1, Walter Millsap and Keikichi Akana Imamura Family Papers. Page 3.

[3] Ibid. Page 1.

[4] Ibid. Page 1.

[5] K. A. Imamura to Walter Millsap, July 22, 1942, box 1, Walter Millsap and Keikichi Akana Imamura Family Papers. Page 1.

[6] Toshiko Imamura to Walter Millsap, August 7, 1942, box 1, Walter Millsap and Keikichi Akana Imamura Family Papers. Page 2.

[7] Walter Millsap to Toshiko Imamura, October 10, 1942, box 1, Walter Millsap and Keikichi Akana Imamura Family Papers. Page 1.

[8] Ibid. Page 1.

[9] Ibid. Page 1.

[10] K. A. Imamura to Walter Millsap, December 16, 1945, box 1, Walter Millsap and Keikichi Akana Imamura Family Papers. Page 1.

[11] K. A. Imamura to Walter Millsap, April 27, 1944, box 1, Walter Millsap and Keikichi Akana Imamura Family Papers. Page 1.

Image credit: File:TulareCountyFairgrounds.jpg – Wikimedia Commons