By Mattie Webb

Following the 1976 Soweto uprising, the international press derided the ongoing episodes of South African police violence against youth protestors, compelling some multinationals to reconsider their operations in a country that denied human rights to the majority of its population. The United States has a history of investment with South Africa. Dating back to the early twentieth century, American multinationals took advantage of South Africa’s abundance of minerals and later relied on the brutal apartheid laws, the legalized state-sponsored segregation on the basis of race (1948-1994), to maximize capitalist extraction. By the 1970s, American corporations could no longer appear compliant with racist apartheid law, nor could they continue business as usual in South Africa. Rev. Leon Sullivan, a Black American civil rights leader and member of the General Motors Board of Directors, would use his platform to reform American business operations in apartheid South Africa.

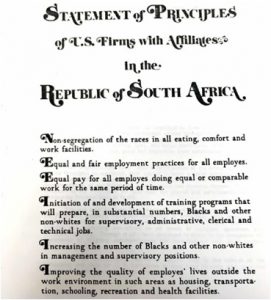

The Sullivan Principles, unveiled in 1977, were Sullivan’s solution. Stipulating desegregation of the workplace and equal pay for equal work, the Sullivan Principles were a code of conduct for U.S. multinationals operating in South Africa. Although voluntary, the Principles were adopted by multinationals that sought to rebrand their image. While much scholarship on the Principles highlights both their shortcomings and successes, in this article I consider the ways internal South African “reforms” to the apartheid workplace enabled Sullivan to modify his code to keep pace with already existent changes within South Africa.[1] I place the Sullivan Principles in conversation with the Wiehahn Commission, an internal South African labor reform.[2] Although both top-down initiatives claimed to center the interests of Black South African workers, they only did so when politically expedient, and the initiatives did little to threaten the most entrenched and violent forms of apartheid.

Image One: Principles.

Reference: The six original Sullivan Principles. Ronald Reagan Presidential Library: CO141 South Africa, Box 166, Folder 318966 (1).

In 1979, two years after the launch of the Sullivan Principles, the South African government issued the Wiehahn Commission, recommending that the labor relations system registers and recognizes multiracial independent trade unions.[3] Together, the Sullivan Principles and the Wiehahn reforms responded to the decolonization of southern Africa, yet both reforms sought to patiently target apartheid in a way that did not agitate the South African government or push multinational corporations too far. This approach did not sit well with the anti-apartheid movement, which was pressing for a total corporate exodus from South Africa.

Many activists were leery of the Principles, drawing attention to the absence of reforms allowing for union representation of Black workers.[4] In 1978, the Statement of Principles Industry Steering Committee, the evaluation committee for the Sullivan Principles, held a series of meetings in South Africa. Their report posited how many of the changes in the laws and customs of South Africa being considered by the Wiehahn Commission began with the Sullivan Principles.[5] While the Principles did not initially outline support for multiracial trade union recognition, the 1979 modification of the code, implemented just four months after the Wiehahn reforms, called on firms to recognize and negotiate with registered trade unions that represented Black workers.

By 1981, the South African government had implemented the Wiehahn recommendations, and for the first time in the history of South Africa, all Black workers gained the right to join trade unions. In 1979, Kellogg became the first U.S. company in South Africa to sign a recognition agreement with one of the new independent unions.[6] Borg-Warner followed Kellogg in 1980 and agreed to plant-level negotiations. Since agreeing to negotiations, the National Automobile and Allied Workers Union at Borg-Warner promptly agreed to wage increases that more than doubled the monthly minimum wage.[7] This progress should be met with skepticism. Though Sullivan signatory evaluations were non-mandatory, both Kellogg and Borg-Warner completed them, with Borg-Warner submitting its first evaluation in time for the October 1980 report. While Kellogg scored a passing, “Category I” score in the Sullivan evaluation, Borg-Warner received a “Category III” score, meaning it “needed to become more active” and “did not meet basic requirements.”[8]

Both Sullivan signatories and non-signatories dismissed workers for strike actions in the years following the Wiehahn Commission report, revealing the ineptitude of the voluntary Sullivan evaluations.[9] In fact, three years after Wiehahn, only nine U.S. companies had signed formal recognition agreements with unions representing Black workers. However, the number of companies receiving top Sullivan ratings far exceeds this number. Consequently, the companies that refused to recognize Black unions received no tangible punishment from the Sullivan evaluation team.[10]

In the context of the late 1970s, however, even members of the apartheid government’s ruling National Party agreed that “petty apartheid” was on its last leg, and the Principles and Wiehahn recommendations merely targeted cosmetic forms of apartheid, such as workplace segregation. Professor Wiehahn, the architect of the Wiehahn Report, supported the Sullivan Principles and urged robust enactment efforts by corporations, even if doing so meant breaking “the petty and outdated apartheid laws.”[11] South Africa’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, Pik Botha, accepted the Sullivan Principles and publicly campaigned for a seat in Parliament on the basis of abolishing petty apartheid, all the while upholding the continued imprisonment of the Black population.[12] Many Black Africans highlighted how Wiehahn did not address the most urgent needs of the Black community, and merely placated investors.[13]

Thus, U.S. multinational companies could yield passing Sullivan scores without actually adhering to the Wiehahn Commission recommendations, such as union recognition and negotiation. The Sullivan clause calling for the “rights of blacks to form or belong to government registered or unregistered unions” lacked an enforcement mechanism. There was no mention of any obligation to bargain in good faith, or to acknowledge full trade union rights. However, the Wiehahn Commission, though intended to stymie political instability, ultimately did provide some space for worker militancy. Such militancy, in the form of work stoppages and strikes, undercut the Sullivan Principles from within. By the mid-1980s, major U.S. multinationals faced a recession and increased labor strife, pressuring them to sell their operations, or at least their majority interest. While both reforms abolished some of the racial characteristics of trade union legislation, such unraveling of petty apartheid operated in the interests of business and foreign investment, and less so in the interests of workers.

Author’s Bio:

Mattie Webb is a Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of History at the University of California, Santa Barbara, where she studies 20th century U.S. foreign relations and African history. Her dissertation, tentatively titled “Diplomacy at Work: The South African Worker and the Sullivan Principles on the Shop Floor,” draws on archival sources and oral histories from the United States and South Africa.

Twitter: https://twitter.com/MattieCWebb

Further Reading

Biko, S. I Write What I Like. Oxford, Heinemann, 1987.

Brown, J. The Road to Soweto: Resistance and the Uprising of June 16, 1976. Woodbridge: James Currey, 2016.

Dudziak, M. Cold War Civil Rights: Race and the Image of American Diplomacy. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000.

Lichtenstein, A. “‘We Do Not Think That the Bantu Is Ready for Labour Unions’: Remaking South Africa’s Apartheid Workplace in the 1970s.” South African Historical Journal 69, 2 (2017).

Lichtenstein, A. “‘We Feel Our Strength is on the Factory Floor’: Dualism, Shop-Floor Power, and Labor Law Reform in Late Apartheid South Africa.” Labor History (2019).

Nesbitt, F.N. Race for Sanctions: African Americans against Apartheid, 1946-1994. Blacks in the Diaspora. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2004.

Noer, Thomas J., Cold War and Black Liberation: The United States and White Rule in Africa, 1948-1968. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1985.

Massie, R. Loosing the Bonds: The United States and South Africa in the Apartheid Years. New York; London: Doubleday, 1997.

Morgan, E.J. “His Voice Must Be Heard: Dennis Brutus, the Anti-Apartheid Movement, and the Struggle for Political Asylum in the United States.” Peace and Change 40, no. 3 (2015).

Plummer, B.G. Rising Wind: Black Americans and U.S. Foreign Affairs, 1935-1960. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996.

Stevens, Simon. “‘From the Viewpoint of a Southern Governor’: The Carter Administration and Apartheid, 1977-81,” Diplomatic History 36, no. 5 (2012).

Stewart, J.B. “Amandla! The Sullivan Principles and the Battle to End Apartheid in South Africa, 1975-1987.” Journal of African American History 96, no. 1 (2011).

Endnotes

[1] Elizabeth Schmidt, Decoding Corporate Camouflage: U.S. Business Support for Apartheid. Washington, DC: Institute for Policy Studies, 1980.; Jessica Ann Levy, “Black Power in the Boardroom: Corporate America, the Sullivan Principles, and the Anti-Apartheid Struggle,” Enterprise & Society 21:1 (March 2020): 170-209.; Zeb Larson, “The Sullivan Principles: South Africa, Apartheid, and Globalization,” Diplomatic History 44:3 (2020): 479-503.

[2] A. Rycroft and B. Jordaan, A Guide to South African Labour Law (Cape Town: Juta, 1992).; S. Bendix, Industrial Relations in South Africa. 3rd ed. (Cape Town: Juta, 1996).; A. Lichtenstein, “‘We Do Not Think That the Bantu Is Ready for Labour Unions’: Remaking South Africa’s Apartheid Workplace in the 1970s,” South African Historical Journal 69:2 (2017).; A. Lichtenstein, “‘We Feel Our Strength is on the Factory Floor’: Dualism, Shop-Floor Power, and Labor Law Reform in Late Apartheid South Africa,” Labor History (2019).; Steven Friedman, Building Tomorrow Today: African Workers in Trade Unions, 1970-1984 (Johannesburg: Ravan Press, 1987), 153.

[3] Prior to Wiehahn, these multiracial unions could not legally register and were not recognized on the shop floor. “Labor and South Africa,” Economy Notes: Labor Research Association, Inc., 53:7-8, UCT African Library Pamphlet Collection, Box 327, Folder 73, University of Cape Town Special Collections (UCT), Jaggar Library, Rondebosch, South Africa, p. 6.

[4] Dorcas Good and Michael Williams, “South Africa: The Crisis in Britain and the Apartheid Economy,” Foreign Investment in South Africa: A Discussion Series, 1 (1976), Box 72, ANC-London, Mayibuye UWC, p. 9.

[5] Report, Statement of Principles Industry Steering Committee, “Visit to the Republic of South Africa,” August 20-26 1978, Box 63, Folder 6, Leon Howard Sullivan papers, Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University, p. 3.

[6] “Labor and South Africa,” Economy Notes: Labor Research Association, Inc., June 1987, 53:7-8, UCT African Library Pamphlet Collection, Box 327, Folder 73, p. 6.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Arthur D. Little, Inc., “Fourth Report on the Signatory Companies to the Sullivan Principles,” October 1980.

[9] The companies included: Chrysler (non-signatory), Coca-Cola, Columbus-McKinnon (non-signatory), Firestone (category II), Standard Oil of Ohio (non-signatory) and City Investing (non-signatory).; See “Labor and South Africa,” Economy Notes: Labor Research Association, Inc., June 1987, Vol. 53:7-8, UCT African Library Pamphlet Collection, Box 327, Folder 73, 6.

[10] See Report, “Church Investors Concerned About US Investment in South Africa: Symposium on Current Issues Facing American Corporations in South Africa,” September 28, 1981, Box 332, Special Collections, UCT Jaggar Library.

[11] Report, Statement of Principles Industry Steering Committee, “Visit to the Republic of South Africa,” August 20-26 1978, Box 63, Folder 6, Leon Sullivan papers.

[12] Report, Harold R. Sims, “South Africa Report #2,” July 1979, Box 64, Folder 7, Leon Sullivan Papers.

[13] Report, Harold R. Sims, “South Africa Report #2,” July 1979, Box 64, Folder 7, Leon Sullivan Papers.

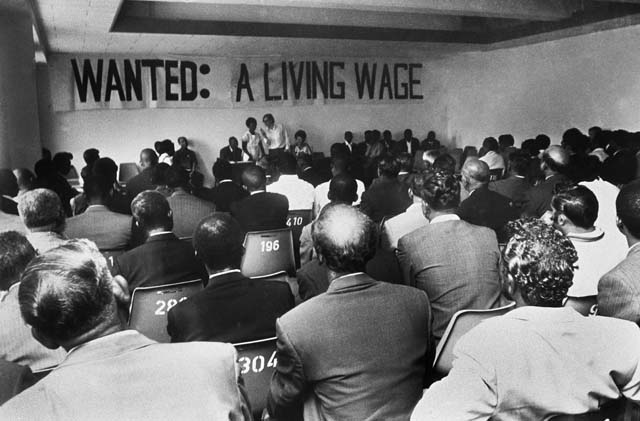

Feature Image: Hemson, David. Strike meeting, 1973, Bolton Hall, Durban. 1973. UCT Libraries Digital Collections, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa. Accessed November 30, 2020. https://digitalcollections.lib.uct.ac.za/islandora/object/islandora%3A18481