By Niels Boender

The sudden ubiquitousness of debates about historical memory, driven by important awakenings regarding systematic injustices, have thrust historians to the centre of what is now popularly called ‘the culture wars’. This offers an opportunity for historians to share their findings in ways that palpably impact understandings of global and national histories, as well as the risk of not reaching out to those that may think differently. This article will argue that engaging with twentieth-century British colonialism, and specific incidents like the Mau Mau Uprising in Colonial Kenya (1952-60), whether in museums, curricula or popular publications, is an important place to start transforming historical understandings.

On this blog, Dr Bhattacharya put forward the case for ‘confronting our national pasts in their entirety’, an opinion with which I wholeheartedly agree, but this needs to be given concrete form by curators, educators and historians. British historical discourse must seek to take the public with it, not alienate it by glibly targeting national icons, and thereby rise above the outrage-stoking discourse of Ministers and Spectator columnists. If one believes in the duty of the historian to mould popular attitudes to the past then we need to speak to people who disagree with, or don’t care about, colonial history.

https://yougov.co.uk/topics/international/articles-reports/2020/03/11/how-unique-are-british-attitudes-empire

People do not consider national histories, ‘in their entirety’, but memorialise specific moments. I would argue that Dutch views are the most positive because, rather than ‘police actions’ against Indonesian nationalists or ‘punitive expeditions’ against indigenous kingdoms, the public remember a ‘Golden Century’ of economic mastery and commercial adventurism. My own childhood in the Netherlands was filled with cultural references to this period, from the spectacular 18th-Century cargo ship in Amsterdam harbour, the ‘East India Company-mentality’ that Prime Minister Balkenende praised in 2006, or the faux-Indonesian decor in Chinese restaurants. By contrast, the violence that undergirded this period was universally absent. In turn, much of the British public envisions the India of Kipling, of memsahibs and hill stations, and not Amritsar, Partition and grinding exploitation. British memory is also influenced by the revitalised rhetoric of ‘kith and kin’, re-dubbing the ‘White Dominions ‘as CANZUK, presenting Empire as a consensual spreading of British ‘values’. Selective remembering is far harder for Belgians, who only have the Congo, or Italians, whose Empire only really got going under Mussolini.

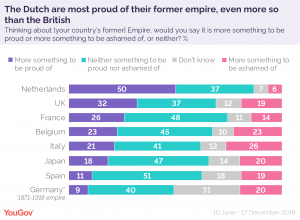

And what does the public think about the Empire? A recent YouGov survey found Britons are the second most likely of former imperial nationalities to be proud of their Empire, second only to the Dutch. Of all these statistics, the unsure or equivocating majorities present a palpable objective for historian’s activism.

Historians have already turned their attention to dismantling Britain’s selective remembering, for instance with an open letter condemning Home Office literature for the citizenship exam, which ignored the brutalities of slavery and presented decolonisation as a consensual process. With slavery now receiving more (needed) attention, for instance in the much-maligned National Trust project, I would posit that late-colonialism and it’s ‘Emergencies’ are a key subject for popular historical production.

The image of decolonisation as consensual, managed and the teleological outcome of colonialism was an attitude cultivated explicitly by British officials in the late-1950s and 60s. These attitudes have remained sticky and reflect the legacies of the very attitudes that underpinned late-colonialism. The racial ideology of colonial administrators in twentieth-century British Africa was not, on the whole, eliminationist or totally dehumanising towards indigenous Africans, as they were in earlier periods, but infantilising, capable of excessive force and viewed non-whites as inherently underdeveloped. This late-colonial ideology, which justified, for instance, the detention camps of the Mau Mau Uprising, is the direct antecedent to the forms of racism that POC face today, and thus requires greater understanding.

The unconscious biases that allow for police brutality in America bear crucial ideological similarities with the actions of camp guards in Kenya during the 1950s, justified in terms of stability, or ‘law and order’. While black resistance was dubbed ‘terrorism’, white settlers were listened to and advantaged in policy. British administrators were incapable of accepting that African Nationalism was a product of genuine racial or economic grievances, instead seeing it as something bestial, tribal and characteristic of an essential African ‘character’. Essentialising discourses regarding POC, as well as double standards over political activism, of course remain potent till this day.

Opponents of contemporary revisionism often argue that one cannot judge colonialism by present standards, but, critically, the pacification of the Mau Mau was faced with significant press, public and parliamentary criticism even when it was happening. Moreover, brutal tactics such as the so-called ‘dilution technique’, which consisted of the punitive beating of detainees (who had not faced any trial), was sanctioned by members of the British Cabinet itself. Historians must inculcate that decolonisation was not a singular moment, when official racism ended by the process of hauling down the Union Jack, but an incomplete and fraught process.

Salman Rushdie once said: ‘the trouble with the English is that their history happened overseas, so they don’t know what it means’. Late-colonial incidents like Mau Mau, are a good place to continue correcting this error, and begin moving towards a reflective assessment of the British past. Incidents such as these can form a powerful reminder of how close colonial violence is to our own lifetimes, with survivors still telling their stories in their twilight years. It is not enough to simply condemn colonial atrocities; there is a serious need for understanding that ideas of a ‘civilising mission’, the very arguments about railroads and Sati that contemporary defenders of Empire raise, allowed for the brutalities like the Kenyan detention camps. Post-colonial states continue to live with the legacies of colonial counterinsurgency, and it is difficult to understand Britain’s place in the world without examining them.

Author’s Bio:

Niels Boender is currently a PhD Student at the University of Warwick, working collaboratively with the Imperial War Museum. His current project studies the legacies of the Mau Mau Uprising in Kenya, with specific focus on the abiding role of ex-detainees and ex-fighters in the local politics of independence.

@NielsBoender

Image: https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205191326.