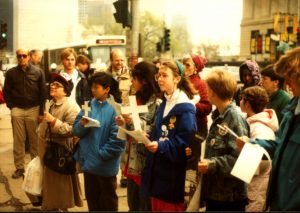

Feature Image: Soweto Day Walkathon in Chicago, June 16, 1988. Link: https://africanactivist.msu.edu/image.php?objectid=210-809-1121 (permission granted by Joan Gerig)

By Zeb Larson

Studies of the anti-apartheid movement have proliferated over the past few years, owed in no small part to greater archival access as well as the legacy of the movement today.[1] The anti-apartheid movement in the United States holds a continuing fascination with activists today because of its scope. Foreign policy and human rights issues can be fickle when it comes to sustaining public attention, but by 1986, support for sanctions was strong enough to pass legislation over Reagan’s veto. Today, activists such as Bill McKibben explicitly cite the anti-apartheid movement as a model for fighting climate change.[2]

Understanding how this movement came together is vital, but trying to understand it from the top-down is not necessarily useful. Prior histories of the anti-apartheid movement in the United States have tended to focus on the national picture taken as a whole, but that is only one part of the picture.[3] National groups like the American Committee for Africa (ACOA) or TransAfrica steered lobbying and publicized the issues around apartheid, but they relied on local support movements and divestment groups in order to generate action. Local movements came together through a combination of church, union, student, and race-based activism.

Moreover, apartheid was not a monolithic issue: it drew in people for numerous different reasons. Anti-racism was an obvious one given the nature of the apartheid government, but there were other factors. As early as 1965, Victor Reuther of the United Auto Workers explained that his opposition to apartheid came from a fear that labor exploitation in South Africa would normalize lower pay and weak unions in the United States.[4] Members of the American Friends Service Committee focused on South Africa’s nuclear proliferation and the threat it posed to regional peace.[5] Pacifists were drawn in who opposed South African violence at home and with its neighbors, as well as the U.S. role in the Cold War. Apartheid also became a way to have conversations about issues in the United States as well by noting their global connections.

A monolithic focus on the anti-apartheid movement and South Africa also obscures the broader struggle for liberation in southern Africa. The struggle against apartheid did not exist in isolation, as activists themselves have emphasized in their own recollections.[6] The struggle against Portuguese imperialism, against the South African occupation of Namibia, and to bring an end to the UDI government in Zimbabwe. These struggles were interconnected: South Africa immersed itself in the Angolan and Mozambican Civil Wars.

The best way to understand this movement may be from a local perspective. Chicago provides an interesting example of how this grassroots movement coalesced amidst diverse interests. It was a city that was targeted by activists at the national level as early as the 1960s. Home to a large African American population that was socially active, it was chosen as a “field office” by ACOA in 1970. ACOA sent Chicago native Prexy Nesbitt to run it.[7] It was home to a relatively large number of South African exiles and expatriates, who brought with them interest in fighting against apartheid.

This attempt to create a national network for anti-apartheid activism quickly foundered. ACOA’s experiment in running a satellite office came to a relatively quick end, partly because of the expense and also because ACOA was known as a “white liberal” group, which made outreach difficult. Nesbitt however remained in Chicago and helped organize a new group, the Chicago Committee for the Liberation of Angola, Mozambique, and Guinea-Bissau (CCLAMG). CCLAMG focused on the Portuguese colonies in part because they appeared to be closer to liberation, but they regarded the two fights as interconnected because of South African support for Portugal. Moreover, the fight against apartheid was for them part of a global struggle against imperialism and capitalism that ultimately came back to the United States.[8]

CCLAMG’s work is a good example of the kinds of work done by grassroots support groups: documentary showings for the public, outreach to sympathetic groups, and fundraising for donations to the liberation movements. It provided a point of entry for many people into solidarity activism. This work continued even after the independence of Angola, Mozambique, and Guinea-Bissau. There were smaller groups such as the Citizen’s Coalition for Southern Africa, which targeted Continental Illinois Bank because of a rumor that it loaned $48 million to the South African government to purchase locomotives, with a guarantee from the Export-Import Bank. They staged picket lines outside of the bank.[9]

Churches were also a significant part of the organizing that went on in Chicago. By 1974, the southern Africa task force of the United Church of Christ in Chicago was organizing “Southern Africa Day,” which included speaking exhibitions by prominent exiled South Africans such as Dennis Brutus.[10] In 1977, Wellington Avenue UCC in Chicago announced that a third of its budget would go to liberation activism. Chicago was also home to a short-lived national group, the Coalition for the Liberation of Southern Africa. Student groups at Northwestern, University of Chicago, and University of Illinois Champaign-Urbana agitated for their campus endowments to divest,

By 1977, these disparate Chicago entities eventually began cooperating in broader anti-apartheid struggles around banking through the Chicago Coalition on Southern Africa (CCSA). CCSA brought together many of the activists in Chicago: CCLAMG, the Wellington Avenue UCC, the U.S. out of Angola Committee (an offshoot of CCLAMG), and other groups such as the Amilcar Cabral Collective and New World Resource Center.

At the time of their establishment in February 1977, their chief issues in opposition to apartheid specifically were supporting an end to bank loans to the South African government and ending the sale of Krugerrands, the South African gold coins. They also began establishing connections with other liberation and liberal groups in the city: disarmament coalitions, civil rights groups such as CALC, white churches, and Puerto Rican liberation groups. Most significantly, CCSA could also reach out to the well-developed civil rights network in Chicago, and groups such as Operation PUSH gave the campaign a great deal more power.

CCSA marked a stronger switch to protests and pickets in front of First National Bank in Chicago while affiliated groups carried out shareholder resolutions to force debate about bank connections to South Africa. This activity led to growing involvement at the local political level as well. In April 1978, one Chicago alderman introduced legislation to prohibit the city from placing funds in institutions doing business with South Africa.[11]

But anti-apartheid activism often happened in cycles, and by 1980, CCSA’s activities wound down for a time. Some of the group’s leadership, like Nesbitt, went abroad; South Africa also receded from the news cycle in the United States. However, much of the group’s membership was reconstituted in 1983 as a new group, the Coalition for Illinois’ Divestment from South Africa (CIDSA). Recognizing that it also could not hope to win a statewide divestment solely through a Chicago constituency, CIDSA began making inroads in other parts of the states, setting up affiliated chapters in Champaign-Urbana, Peoria, Rockford, and Carbondale. Members began organizing statewide conferences to draw activists together: the first such meeting drew approximately 75 people in early 1984, and a conference was held for downstate organizers in 1985 that drew another 75 people. These statewide lobbying networks were judged to be effective in terms of forcing bills out of committee in 1985.[12]

CIDSA made inroads with labor unions as well, drawing them more closely into the anti-apartheid movement. White-collar unions such as AFSCME or the Chicago Teachers’ Union were vital allies because their pension funds were the ones affected by divestment, but blue-collar unions were equally important. One of the arguments against divestment was that it would hard the economy at a time when Illinois was deindustrializing: CIDSA found creative ways to argue against that, noting for example the importation of South African steel even as Illinois’ steel industry collapsed.[13] To win over unsympathetic legislators in more rural parts of the state, those legislators were lobbied through their churches. Finally, in 1986 CIDSA and their sympathetic legislators decided to weaken some of the bill’s provisions to prohibit future investments by the pension fund in South Africa-affiliated companies, and which passed in 1987.[14]

While its focus had been on the state, CIDSA members had participated in letter-writing, phone calls, and demands to Congress for federal sanctions to be passed over Reagan’s veto, the high-water mark of the anti-apartheid movement. This is one of the critical pieces in understanding how a national anti-apartheid movement ultimately came together: it happened through these local campaigns. Activism waxed and waned, and many of the issues were ultimately symbolic: blocking krugerrand sales did not harm South Africa’s economy, but it did raise awareness about apartheid.

Insights

Examining the local raises both insights and questions about the anti-apartheid movement in the United States. Chicago highlights some of the interplay between different factions: leftists, African American groups, churches, unions, and students. A close look at the local nature of it reveals how some of these paradoxical connections were maintained. Chicago’s activism was driven by leftist groups and churches, which might seem counter-intuitive except for certain local connections that made it possible. Nesbitt, who was present in Chicago for so much of this movement, had been raised in a UCC church and knew many of the active groups. Similarly, he worked as a teacher, and used his own union connections as much as possible to win over their support.

Similarly, the focus on Chicago’s local movements highlights the interconnectedness of these liberation movements. Using Nesbitt as an example, he began by focusing closely on the Portuguese colonies. Moreover, that was an issue he returned to: he founded the Mozambique Support Network and worked as a consultant for the Mozambican government directly from Chicago. While he drove much of this, he also relied on a network of cooperantes (volunteers who had gone abroad to work in Mozambique after the Portuguese left) in Chicago and elsewhere.

Cassinga Day, 1989. Cassinga Day commemorated the massacre of Namibian refugees in Angola in 1978 by the South African Defense Forces. Link: https://africanactivist.msu.edu/image.php?objectid=210-809-1152 (permission granted by Joan Gerig)

Examining these local movements also makes clear how Republicans and moderates were won over to support sanctions against South Africa. Even in Chicago, the city was paralyzed by the so-called Council Wars during the 1980s, and the city was dominated by powerful business interests that opposed divestment. Rural Illinois remains politically conservative, but Chicago-based activists were able to help develop a statewide network pushing for divestment and sanctions. More work needs to be done to explore this issue.

Finally, attention to the local nature of these movements will provide greater insight into why apartheid resonated with such a diverse constituency. As I mentioned in the above paragraph, the battle to force Chicago’s divestment happened at the same time as the Council Wars, which pitted more moderate Democrats and Republicans against a more progressive wing of the party. Opponents of apartheid often criticized capitalistic forces that drew money away from local communities and toward oppressive governments. How much was the anti-apartheid movement rooted in an anti-globalist sentiment, as an example? These are all questions worth considering.

Author’s Bio: Zeb Larson received his PhD in history from The Ohio State University in 2019. His dissertation, “The Transnational Dimensions of the U.S. Anti-Apartheid Movement” is currently being adapted into a monograph. In 2020, he published an article in Diplomatic History, “The Sullivan Principles: South Africa, Apartheid, and Globalization.” He’s also working on an article expanding on Chicago’s role in the anti-apartheid movement.

Further Reading:

Nicholas Grant, Winning Our Freedoms Together.

Robert Massie, Loosing the Bonds.

Francis Nesbitt, Race for Sanctions.

Simon Stevens, Boycotts and Sanctions Against South Africa.

Joe Parrott, Struggle for Solidarity.

Zeb Larson, The Transnational Dimensions of the U.S. Anti-Apartheid Movement.

Endnotes

[1] Examples include Nicholas Grant’s Winning Our Freedoms Together, Robert Massie’s Loosing the Bonds, and Francis Nesbitt’s Race for Sanctions, but also dissertations such as Simon Stevens’ Boycotts and Sanctions Against South Africa, Joe Parrott’s Struggle for Solidarity, my own dissertation The Transnational Dimensions of the U.S. Anti-Apartheid Movement, and forthcoming scholarship by Amanda Joyce Hall and Mattie Webb.

[2] Bill Moyers, “Bill McKibben on Divesting from Fossil Fuels,” April 24, 2014. Accessed February 1, 2021: https://billmoyers.com/2014/04/24/bill-mckibben-on-divesting-from-fossil-fuels/.

[3] One of the best-known examples is Robert Massie’s Loosing the Bonds: The United States and South Africa in the Apartheid Years.

[4] Letter from Victor Reuther, April 28, 1965, MSU, MSS 294, Box 1, Folder 2.

[5] Nationwide Peace Education Division Committee Meeting January 7-9, 1983, AFSC, AFSC Minutes 1983, BDE to PE, 1983 Minutes Peace Education.

[6] See No Easy Victories by Bill Minter, Gail Hovey, and Charles Cobb, Jr.

[7] Prexy Nesbitt Report to ACOA, April 16, 1970, ACOA.

[8] Chicago Committee for the Liberation of Angola, Mozambique, and Guinea-Bissau Statement of Philosophy, Accessed February 20, 2021: https://projects.kora.matrix.msu.edu/files/210-808-8657/african_activist_archive-a0b3e6-a_12419.pdf.

[9] Interview with Prexy Nesbitt, July 1, 2009; “Pickets Assail Bank Here on South Africa,” The Chicago Defender, March 28, 1972.

[10] Southern Africa Day leaflet, Accessed February 26, 2017: http://kora.matrix.msu.edu/files/50/304/32-130-726-84-african_activist_archive-a0b5o9-a_12419.pdf.

[11] “Continental’s Loan Policy Hit,” Chicago Tribune, April 25, 1978.

[12] Final Report from CIDSA, December 1987, Madison Historical Society, Prexy Nesbitt Papers, Box 5, CIDSA 1 of 2; CIDSA Update No. 2, Accessed April 3, 2017: http://kora.matrix.msu.edu/files/50/304/32-130-4B4-84-african_activist_archive-a0b2e7-a_12419.pdf; CIDSA Update No. 11, Accessed February 4, 2019: http://kora.matrix.msu.edu/files/50/304/32-130-4CA-84-african_activist_archive-a0b2h3-a_12419.pdf; CIDSA Update No. 14, Accessed February 4, 2019: http://kora.matrix.msu.edu/files/50/304/32-130-4CE-84-african_activist_archive-a0b2h8-a_12419.pdf.

[13] April 9, 1985 Press Release, Madison State Historical Society, Prexy Nesbitt Papers, Box 6, State-wide Tour April ’85; May 1, 1985 CIDSA Press Release, Madison State Historical Society, Prexy Nesbitt Papers, Box 6, CIDSA Press Releases ’85.

[14] Interview with Basil Clunie, Spring 2009, https://digitalcommons.colum.edu/cadc_caam_oralhistories/7/.