By Tom Shillam

As Christopher Lee has written, decolonisation in the mid-twentieth century constituted ‘a complex dialectical intersection of competing views and claims over colonial pasts, transitional presents, and inchoate futures’ as much as ‘a linear, diplomatic transfer of power’.[1] This is also an observation which scholars of the transnational cultural and intellectual histories of different regions of Africa and Asia have made. Many activists in these regions beyond the familiar pantheon of political leaders – the so-called ‘Bandung Generation’ – fleshed out and exchanged eclectic visions of world futures in the global 1950s and 1960s in league with far-flung communities of friends and contacts.[2]

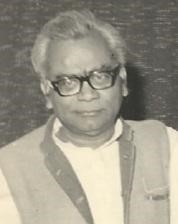

One concept whose currency was significant in the networked Afro-Asian internationalisms of this period was ‘socialism’. For many activists, ‘socialism’ invoked a democratic and egalitarian imagined future which bookended imperialism. At the turn of the 1950s, a number of anti-imperialists from India, Burma, and Indonesia – all countries which achieved independence in the late 1940s – came together around the idea of formulating a socialist internationalism which realised broad aspirations towards a global future free of exploitation, poverty, and inequality. They hoped to engage with sympathetic parties around Asia and Africa who had similar ambitions. Meeting Lebanese socialists in 1951 for ‘a series of discussions and intimate conversations’, Indian socialists including Ram Manohar Lohia, pictured below, professed ‘faith in a new socialism…which alone will be capable of becoming even among the least organised groups, a massive victorious instrument of the liberation of man and masses’.[3]

Figure 1[4]

Copious similarly intimate meetings took place over the early 1950s in South and Southeast Asia as well as further afield. Organisations such as the Asian Socialist Conference (ASC) were founded, which enabled members to share ideas at seminars, in publications, and through shared transnational excursions where they observed industrial and agricultural experiments underway in locations such as Yugoslavia. These initiatives were threaded through mobile intermediaries who flitted from one city or country to another forging friendships and padding out contact books. The intermediaries were often not majestic personalities such as Lohia, but characters at the periphery of domestic politics who had more time for internationalist strategising.

Collectively, Asian socialists and African freedom fighters nurtured the idea of constituting a ‘Third Force’ in world politics which challenged imperialism, and evolved what contributors to the first ASC congress in Rangoon in 1953 termed ‘a system whereby the entire mass of the people could be associated with economic and political activity’.[5] This differed considerably from what one Asian socialist termed ‘white socialism’, or ‘Western European socialism’, which showed itself to be ‘an imperialist ideology’ in its indifference towards ongoing freedom struggles.[6] ‘People’s Socialism’, as one Indonesian columnist called it, would channel the energies of African and Asian peoples who had just achieved independence themselves – rather than limiting itself to parliamentary activity.[7] It also envisioned usurping the other blocs in the Cold War by popular appeal – people in parts of the world wracked by ideological conflict would see that only Asian socialism, concerned with ideals rather than ideas, could achieve world peace.

This vision became harder to sustain into the mid-1950s as socialists lost political sway in key countries in Asia.[8] A rival non-aligned internationalism emerged with the Bandung Conference – many of whose spokespersons professed faith in ‘a socialistic pattern of society’ themselves, to quote Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. This pushed Asian socialists who disdained the technocratic and developmentalist tone of these leaders further afield – sometimes into the ‘Western European’ social-democratic circles they had earlier eschewed – where they attempted to change the discourse away from the supposed confrontation between ‘democracy’ and ‘totalitarianism’ towards the confrontation between imperialism and independence struggles. Even so, they continued to try and fashion the links that might foster an anti-imperial socialism on their international excursions; in 1957, one Burmese socialist made it to the Ghanaian independence celebrations, succeeding in renewing ‘old acquaintances and making new friends too’.[9]

Again, manifest in these meetings was an affective internationalism more than an ideological one. It imbibed the energies of anti-imperial activists who aspired to construct a socialist society after independence around the emotional connections they drew with far-flung comrades rather than around a concrete philosophy. With this in mind, it is worth pluralising our understandings of the global intellectual history of socialism(s) in the mid-twentieth century. Decolonisation produced a host of new and different socialisms and internationalisms. These entangled with state-building projects at home as well as contending socialist or non-aligned internationalisms but also spoke to the worldmaking aspirations of countless little-known actors. These socialisms can be approached through a biographical method which pieces together the movements, arguments, and interactions of key intermediaries in the global 1950s and 1960s.

Author’s Bio: Tom Shillam is a 3rd year PhD student at the University of York, currently researching socialist internationalisms in South and Southeast Asia during decolonisation. He previously studied at the University of Leicester and Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin.

Endnotes

[1] Christopher Lee, introduction to Making a World After Empire: The Bandung Moment and its Political Afterlives, edited by Christopher Lee (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2010).

[2] Su Lin Lewis, and Carolien Stolte, eds. “Other Bandungs: Afro-Asian Internationalisms In the Early Cold War.” Special issue, Journal of World History 30, nos. 1-2 (June 2019).

[3] A Reviewer, “The Right of The Way,” Socialist Asia 2, no. 10 (Anniversary Number, 1954): 10.

[4] Viksb, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

[5] Report of the First Asian Socialist Conference (Rangoon: An Asian Socialist Publication, 1953), 99.

[6] “Asian Socialist,” “European Socialism and Asia,” Janata, Mar 11, 1948, 12.

[7] Sitorus, “Asian Socialist Today,” Socialist Asia VI, no. 1 (May 1957): 6-7.

[8] Su Lin Lewis, “Asian Socialism and the Forgotten Architects of Post-Colonial Freedom, 1952-1956,” Journal of World History 30, nos. 1-2 (June 2019): 81-82.

[9] “Report of the Secretary to the Second Bureau Meeting of the Second Term held in Kathmandu,” Prem Bhasin Papers (Socialist Party), fol. 32, NMML, 86-87.

Feature Image: Viksb, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons