By Bondita Baruah

The catastrophic Partition of India in 1947 directed the trajectory of modern Indian history, dividing the country on religious lines, Hindus and Sikhs being assigned India while Muslims were granted Pakistan and East Pakistan (now Bangladesh). The exodus of twelve million people that moved in between the newly built borders led to about a million deaths. The rift between religions indulged a violent fanaticism that may be termed as what Samuel Huntington calls a “clash of civilizations” in South Asia. David Gilmartin classifies in “The Historiography of India’s Partition: Between Civilization and Modernity” that Partition had more to do with what came into the package of modernity: “partition’s root causes lay precisely in the very forms of ‘modern’ knowledge that gave license to the large-scale, ‘essentializing’ cultural values that led to the imagining of religion as historical actors at the core of bounded “civilizations.” (24) Rejecting the long prevalent civilizational relations between Hindus and Muslims in the subcontinent, this view defined those relations on colonial European structure of thought projecting them as separate and opposing elements, “visions of self contained, bounded religions” (24) that led to the partition of India into India and Pakistan and later Bangladesh amidst mass violence and atrocities.

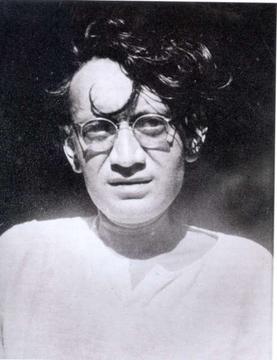

Saadat Hasan Manto is a popular short story writer born in Ludhiana of undivided India who was compelled to leave what he called his second home, Bombay, for Pakistan at the outbreak of the communal frenzy. Against the grand narrative of a nation in the making after the departure of the British Raj, in his stories, Manto strategically made representations of the brutalities of Partition resulting from religious fanaticism, without ever mentioning the name of any religion. Manto’s stories have shown how atrocities were conducted not only against different groups but also upon the people of one’s own religion, whether deliberately or not. This piece will make an analysis of two such short stories in light of the argument that there is little difference between being a protective rescuer and a victimizer who inflicts violence upon one’s own race.

In the story “Mishtake”, Manto writes,

Ripping the belly cleanly, the knife moved in a straight line down the midriff, in the process slashing the cord, which held the man’s pyjama in place. The one with the knife took one look and exclaimed regretfully, ‘Tut tut tut! …Mishtake.’ (Manto 409)

The story presents two sets of characters, caught in the act of murder to forge their allegiance and loyalties towards their religion. Considering the other person as belonging to another religion, the murderer slits his stomach open and cuts across the string of his pyjamas, letting it loose. When he catches sight of the man’s penis, he realizes he had killed his own brethren. What happens when the sword that was raised to kill one another happens to kill one’s own? The murder did not seem to lead to a loss of identity for the murderer as he labeled the act only as a ‘mistake’.

Amaratya Sen delineates identity as a plural construct, an individual being made up of the various cultural compositions he is associated with. Often times an individual preferring one of his identities over the other leads to what Sen calls “identity disregard”, a deduction demanding “singular affiliation” when it is assumed that “any person preeminently belongs, for all practical purposes, to one collectivity only—no more and no less.” (Sen 20)

The weapon of singular affiliation as Sen calls it, was used by sectarians and separatists during the division of the country to identify their religious identity as the only mode of affiliation. The religious fanaticism was a result of this assertion leading to innumerable and callous killings.

Manto’s story “Open It” is another expression of how people of the same religion who were providing protection became poachers. In the course of the dreadful migration that followed the Partition of 1947, people who owned land on either side of the borders of India and Pakistan were rendered homeless and branded refugees. Sakina was the only family her father had, after having lost his wife. While both father and daughter were fleeing to catch a train to cross the border, along with hundreds of others, Sakina’s dupatta (scarf) fell down on the ground. The dupatta is an adornment to the salwar- kameez and since the female body is often sexualized, the scarf is worn on top of the kameez to hide the breasts from male gaze. Wearing the dupatta is a calibrated act to determine how honourable or modest a woman is. As women belong to a gender that is considered subordinated, lesser, and inferior to the male counterpart, a dupatta is symbolically regarded as a patriarchal tool to assert control and hierarchy so that women remain in a demarcated boundary within the society. So her father searches for the dupatta amidst the crowd despite her pleas to stop doing so and once he finds it, Sakina is gone, nowhere to be found. The desperate father arrives at a refugee camp and approaches a group of young men who were rescuing people of their religion– saving lives, searching for lost ones. These so-called protectors of their religion assure the father to find Sakina, and bring her back to him. Days pass by without any news, and one day four men carry a corpse-like body to the refugee camp– it was Sakina. On noticing the dull and drab room, the doctor who had come to examine her instructed the window to ‘open it’ to let in some light. The unconscious Sakina loosens the knot of her salwar at the instruction. Her father, on observing movement in his daughter’s body, is elated that she is alive; meanwhile a fresh stroke of sweat runs down the doctor, who understands why Sakina unfolded her pyjamas at the instruction ‘open it’.

The Pavlovian response to the command ‘open it’ that made Sakina oblige to loosen her salwar strings portends towards the repeated number of times she has heard the two words before being raped. When the father approaches the rescuers, conventional orientation of ‘the male as the protector’ compels us to an awareness that the girl would be rescued by the chivalrous young men. Sakina’s rescuers were fanatics who bore their religious identity to save the people of their own religion.

With Sakina, her rescuers turned out to be her victimizers; these men kept her alive so that they could repeatedly rape her. In the midst of the fear, while she succumbed to the horror of their threats, perhaps her only hope was to stay alive.

Manto’s stories blur the boundaries between us and them, which he has achieved in these two stories. Gyanendra Pandey states that in the act of violence, nations, communities and states draw boundaries by demarcating between ‘us’ and ‘them’. They employ this stratagem “pronouncing the act of violence an act of the other or an act necessitated by the threat to the self” (177). As a nationalist discourse, such a stratagem of violence may sound rhetorical to be sanctioned to maintain ‘national’ uniqueness and glory, at the individual level, however, there is no consecration in such an act for in Manto’s stories, “Mishtake” and “Open it”, the ‘them’ becomes the ‘us’. Manto in his most effective description subverts paternalism through narratives of rescue and protection thereby projecting that the threshold between boundaries, between the ‘us’ and ‘them’, is rather fluid and liminal.

Author’s Bio: Bondita Baruah is presently pursuing her Ph.D research on the stories of Saadat Hasan Manto from the Department of English, North Eastern Hill University, Shillong. She has obtained her M.Phil on Milan Kundera from Gauhati University, Guwahati. Besides having worked as an Assistant Professor in Dispur College (Guwahati, Assam) for almost seven years, Baruah is also a freelance writer and translator. Apart from her academic work, she has worked on translation projects for authors in Assam and also for papers like The New York Times and Stories Asia. She has a recent journalistic piece published in The Third Pole.

Email: baruah3107@gmail.com

Her twitter handle is @BaruahBondita

Bibliography

Gilmartin, David. “The Historiography of India’s Partition: Between Civilization and Modernity”. The Journal of South Asian Studies 74.1 (2015): 23-41.

—. “Partition, Pakistan, and South Asian History: In Search of a Narrative.” The Journal of Asian Studies 57.4 (1998): 1068-1095.

Hardgrove, Anne. “South Asian Women’s Communal Identities.” Economic and Political Weekly 30.39 (1995): 2427-2430.

Huntington, Samuel P. The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of the World Order. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1996. Print.

Jalal, Ayesha. The Pity of Partition: Manto’s Life, Times, and Work Across the India- Pakistan Divide. Noida: Harper Collins, 2013. Print.

Manto, Saadat Hasan. Bitter Fruit. Ed and Trans. Khalid Hasan. Gurgaon: Penguin Books, 2008. Print.

—. Manto: Selected Stories. Trans. Aatish Taseer. Noida: Random House India, 2008. Print.

Pandey, Gyanendra. Remembering Partition: Violence, Nationalism and History in India. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001. Print.

Shapiro, Michael J. “Partition Blues.” Alternatives: Global, Local, Political 27.2 (2002): 249-271.

Sen, Amaratya. Identity and Violence: The Illusion of Destiny. London: Penguin Books, 2006. Print.