By Oliver Wilson-Nunn

The ways in which we understand prisons are filtered through the lens, quite literally, of cinema and television. As criminologists have long remarked, the distance separating many of us, both socially and spatially, from these often-secretive institutions is such that moving images have come to be privileged windows—albeit dirty and cracked—onto this unknown reality.

There is little doubt that films distort prison realities. From a historiographical perspective, however, the comparison of mass-cultural images with lived prison realities in a scholarly ‘spot the difference’ is precluded by the scarcity of sources providing a perspective of prison ‘from below’. In the available documents, the voice of prisoners has been invariably filtered, Argentine historian Lila Caimari reminds us, through those of journalists, criminologists and prison authorities.[1]

A more fruitful way to approach moving images of prisons as primary sources is to examine how, circulating in specific social and cultural contexts, they make us feel about our own relationship to incarcerated people. What do films show us about our place in the social, economic and racial inequalities on which the selectivity of imprisonment is founded? Ultimately, how do images structure our understanding of the enticing, evasive concept of justice? The focus changes from what images show us about prisons as distant and inaccessible spaces, to what they make us feel about imprisonment as a wide-reaching phenomenon from which no-one is truly external.

This change in perspective takes on particular importance in Argentina, where the feelings of those outside prison affect the lives of those entangled in the criminal justice system. Since the sunset years of Carlos Menem’s neoliberal presidency in the late 1990s, rising incarceration rates, calls for a lower age of criminal responsibility and extended prison sentences have been partly grounded in the widespread desire that prisoners ‘rot, not learn’,[2] in the imagined moral chasm between ‘us’, the honest, decent, hardworking citizens and ‘them’, the deviant criminals.[3] The intensity of such feelings and identities often come close to breaking point. For example, the emotional memory of the kidnapping and murder of engineering student Axel Blumberg in 2004 and the outrage (particularly among the middle classes) that ensued still influences widely held beliefs regarding the supposed ‘leniency’ of Argentine criminal justice and the ‘barbarism’ of all people in prison.

The historical challenge is to understand which emotions prop up the legitimacy of incarceration, how these feelings have come about and what role moving images have had in producing, intensifying or indeed challenging them. Whereas there is a rich body of literature on the history of incarceration in North American film and television, the corresponding historiography for Argentina and Latin America is sparse. This is unsurprising given that there have been over three-hundred Hollywood prison films,[4] but only around twenty Argentine fiction films that are set predominantly in prisons. By changing our focus from prisons to imprisonment, however, we can move beyond the ‘prison-film’ genre. Rather than focussing solely on representation of life inside prison, we might trace how the compassion or hatred felt towards prisoners and the fear of or indifference towards punishment experienced by those outside prison structure many filmic narratives, irrespective of genre.

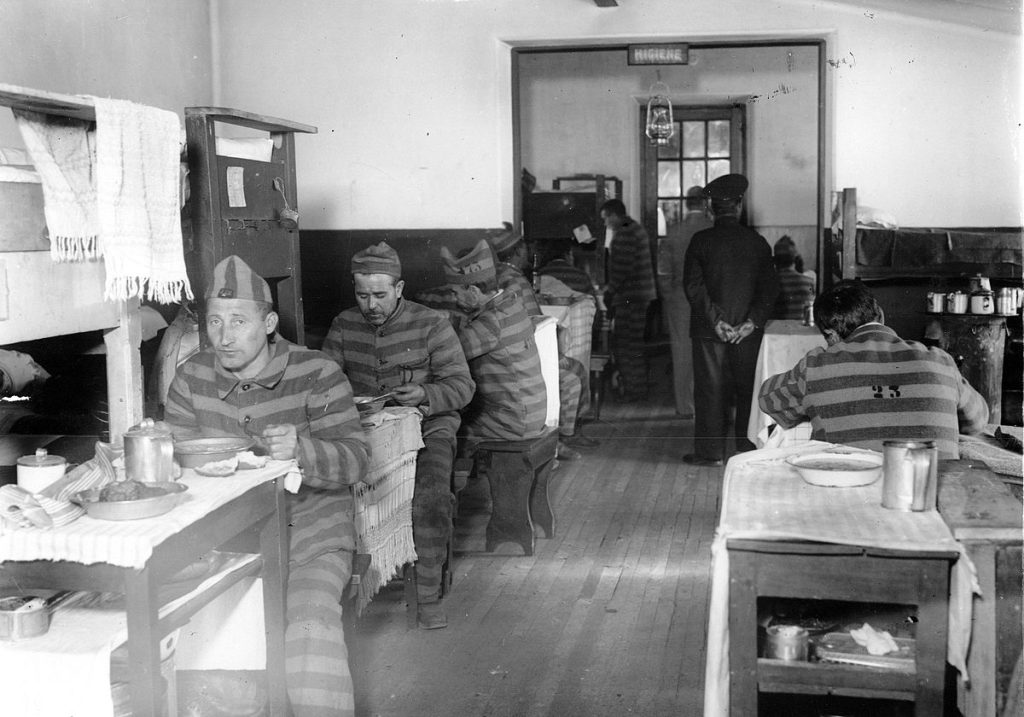

While there is no consistent ‘prison film’ in Argentina, there is continuity—between at least the 1930s and the present day—in the pervasive influence that moving images exert on popular imaginaries of imprisonment. A 1933 report of Ushuaia prison—Argentina’s ‘Siberia’—by popular journalist and author Juan José de Soiza Reilly has the subtitle, ‘Cinematic parade of human beings warped by endless passions’ [Desfile cinematográfico de seres humanos retorcidos por todas las pasiones]. Here, a cinematic imaginary is invoked to generate intrigue and compassion. Even beyond the cinema screen, film is mobilised as a way of developing a deep understanding of the inner feelings and life stories of those imprisoned within institutions that were generally considered ‘premodern’ and inhumane.

Report on Ushuaia. Juan José de Soiza Reilly, ‘Almas y sombras del presidio de Ushuaia’, Caras y Caretas, 6 May 1933. (Accessed from Hemeroteca Nacional de España: http://hemerotecadigital.bne.es/issue.vm?id=0004718674&search=&lang=en)

Fast-forward to 2020 and, although widespread fraternity with prisoners has transformed into hatred, and while despair about the harshness of prisons has given way to disappointment that they are not cruel enough, the influence of moving images continues to spill over into other media, other forms of looking at and feeling about imprisonment. In March 2020, incarcerated people in several Argentine prisons staged riots in response to the danger posed by COVID-19, overcrowding, and poor sanitary conditions. Within hours, photos of Devoto prison in Buenos Aires went viral on Twitter. Many humorous memes framed the riots in relation to characters and episodes from Sebastián Ortega and Adrián Caetano’s immensely popular prison-drama series El marginal. These comparisons lay bare the emotional and political consequences of prison images. The supposedly uncanny connections between fiction and reality not only obscured but delegitimised the prisoners’ calls for safety. Riots in El marginal are motivated by individuals hungry for money, power, and sex even when they are expressed, as in the final episode of Season 2, in the political language of rights, safety and opportunities. El marginal makes people feel mistrusting of the ‘legitimacy’ and ‘authenticity’ of the fears and desires of the incarcerated. It is thus unsurprising that the later, limited transferral of some prisoners to house arrest provoked fear and intense anger towards the government, more so than in other countries—such as Brazil—in which similar measures were taken.

Cultural and journalistic representations of imprisonment in both 1930s and present-day Argentina are inseparable from filmic and/or televisual imaginaries. At both moments, popular attitudes towards imprisonment are deeply pessimistic. In the 1930s, mass-cultural accounts of prisons typically elicited empathy for the imprisoned while encouraging negative feelings towards a repressive state in a period of political repression and corruption known as the ‘Infamous Decade’. Passing from 1930s melodramas, through filmic eulogies of prison reform in the 1950s, to women-in-prison sexploitation films in the 1980s, right up to contemporary Netflix series, solidarity has faded while fear and rage have grown. Studying incarceration in moving images allows us to understand these changes and take stock of our own stakes in the perpetuation of social and criminal injustices.

Author’s Bio: Oliver Wilson-Nunn is a PhD candidate in the Centre of Latin American Studies at the University of Cambridge. His main fields of interest are Latin American cinema and cultural representations of crime, imprisonment and criminal justice. More information here.

Further Reading

Aguilar, Gonzalo, ‘Culpable es el destino: el melodrama y la prisión en las películas’, Nueva Sociedad 208 (2007), 162–78.

Caimari, Lila, Apenas un delincuente. Crimen, castigo y cultura en la Argentina, 1880-1955 (Buenos Aires: Siglo XXI Editores, 2004).

Cecil, Dawn, Prison Life in Popular Culture: From The Big House to Orange is the New Black (Boulder, Colorado: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2015).

Ferrini, Ayelén, ‘Representaciones políticas de la Argentina en las series televisivas Tumberos (Adrián Caetano, 2002) y El marginal (Luis Ortega, 2016)’, Toma Uno 7 (2019), 33–45.

Griffiths, Alison, Carceral Fantasies: Cinema and prison in Early Twentieth-Century America (New York: Columbia University Press, 2016).

Mason, Paul, ‘Relocating Hollywood’s Prison Film Discourse’, in Captured by the Media: Prison Discourse in Popular Culture, ed. Paul Mason (Uffculme: Willan Publishing, 2005).

Rodríguez, Rodolfo, and Ricardo Rodríguez, ‘Deshonra o la trama enrejada del cine y la política’, Nuevo Mundo Mundos Nuevos 8 (2008). https://doi.org/10.4000/nuevomundo.25902.

Rodríguez Alzueta, Esteban, ‘Circuitos carcelarios: el encarcelamiento masivo-selecto, preventivo y rotativo en Argentina’, in Circuitos carcelarios: estudios sobre la cárcel argentina (La Plata: Ediciones EPC, 2015).

Setton, Román, ‘Tumberos: crímenes entre hombres. Engaños y lealtades, confinamientos y libertades’, Badebec 4.8 (2015), 384–406.

Sozzo, Máximo, ‘Populismo punitivo, proyecto normalizador y “prisión-depósito” en Argentina’, Sistema Penal & Violência 1, no. 1 (2009): 33–65.

Wilson-Nunn, Oliver, ‘Pedagogy Behind and Beyond Bars: Critical Perspectives on Prison Education in Contemporary Documentary Film from Argentina’, Latin American Research Review, (Forthcoming 2022).

Endnotes

[1] Lila Caimari, Apenas un delincuente. Crimen, castigo y cultura en la Argentina, 1880-1955 (Buenos Aires: Siglo XXI Editores, 2004), 23.

[2] Esteban Rodríguez Alzueta, ‘Circuitos carcelarios: el encarcelamiento masivo-selecto, preventivo y rotativo en Argentina’, in Circuitos carcelarios: estudios sobre la cárcel argentina (La Plata: Ediciones EPC, 2015), 22.

[3] Máximo Sozzo, ‘Populismo punitivo, proyecto normalizador y “prisión-depósito” en Argentina’, Sistema Penal & Violência 1, no. 1 (2009): 33–65.

[4] Paul Mason, ‘Relocating Hollywood’s Prison Film Discourse’, in Captured by the Media: Prison Discourse in Popular Culture, ed. Paul Mason (Uffculme: Willan Publishing, 2005), 191.

Feature Image: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tierra_del_Fuego_-_C%C3%A1rcel_del_fin_del_mundo_de_Ushuaia.jpg