By Kate Rivington

Scholars have long recognised the importance of religious ties to the formation and maintenance of reform networks. Most notably, for transatlantic abolitionism, scholars have recognised the importance of long-standing Quaker connections, like those dating back to the late eighteenth century between the London-based Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade and the Pennsylvania Abolition Society. However, the historiographical dominance of Quaker networks means that less attention has been paid to other religious networks and their relationship to reform, such as Congregationalism.

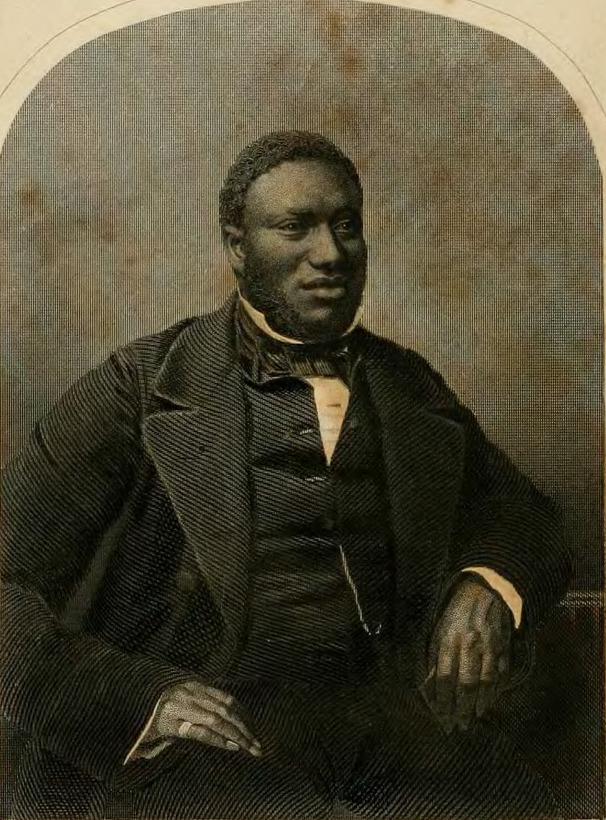

An analysis of the transatlantic trajectory of Black abolitionist Samuel Ringgold Ward highlights the importance of his religious network to his antislavery activism. A Congregational minister, Ward was born into slavery in eastern Maryland on October 17, 1817. At a young age he escaped slavery with his family. Ward settled in New York where he attended the African Free School alongside his second cousin Henry Highland Garnet. A powerhouse orator, Ward spent a few years living in Canada before travelling to Britain in 1853 to begin a years-long speaking tour to raise funds for the Anti-Slavery Society of Canada.

Ward’s religious network dictated his antislavery activism in Britain as his Congregational links influenced which abolitionists he sought out and interacted with. Most importantly, Ward’s Congregational connections meant that he sought to align himself with the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society (BFASS) while in Britain. Transatlantic abolitionism could be loosely split into two camps – the Garrisonians – those who aligned themselves with American abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison – and those who were not aligned with/opposed the Garrisonians. The BFASS, formed in 1839, fell into the latter category. While many American antislavery lecturers visiting Britain sought out key Garrisonian allies like Elizabeth Pease and Richard D. Webb to assist them, Ward focused his attention on drawing assistance from the BFASS and its contacts.

As soon as he arrived in London, Ward headed to the offices of the BFASS at 27 New Broad Street. One of the main reasons that Ward chose to seek out the BFASS was because of his close connection to the pastor of his Congregational church Canada – John Roaf. Ward travelled to Britain with a letter of introduction from English-born Roaf, addressed to Congregationalist minister and BFASS member Thomas Binney. As Ward recalled in his autobiography, upon his arrival in rainy London, “the Rev. Thomas Binney… received me most kindly.”[1] On the advice of Roaf, Ward also sought out Thomas James of the Colonial Missionary Society, of which Roaf was a member. James helped Ward organise a meeting to publicise his antislavery cause at Freemasons’ Tavern on Great-Queen Street on the 21st of June. This meeting would prove vital for the success of Ward’s tour, which raised a total of $7,000.[2] Following his address at the meeting, a committee was formed to assist Ward’s fundraising, comprising the Earl of Shaftesbury, as well as leading members of the BFASS George W. Alexander and Louis A. Chamerovzow.”[3]

Also present at the meeting and joining the committee was James Sherman, who would become one of the most important members of Ward’s Congregationalist network. Sherman was an abolitionist and minister of the Surrey Chapel in Southwark, London. He welcomed Ward as a guest into his home for months during his lecture tour, and introduced him to other abolitionists, most notably Harriet Beecher Stowe, who also stayed with Sherman during the time of Ward’s residence.[4]

Ward’s Congregational links also enmeshed him in a network that was deeply involved in missionary activity, which drew the ire of many Garrisonians. Through his connection to the Earl of Shaftesbury, Ward endorsed the Turkish Mission Aid Society (TMAS). The TMAS was associated with the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM), which many abolitionists denounced due to its links to slaveowners. Writing to a fellow abolitionist, one Garrisonian wrote of his “deep disgust and indignation which I feel at the conduct of Samuel R. Ward” for “endorsing the Christianity of an organization that has done more than any other in the world to prevent the escape of the slave.”[5] Such backlash from abolitionists led to Ward withdrawing his support for the TMAS. Thus, while Ward’s transatlantic Congregational ties proved helpful for his fundraising mission, they also led to unwanted backlash from fellow abolitionists, reminding us that abolitionism was never a cohesive movement – rather, it was plagued by conflicting ideologies and factionalism.

In 1855 Ward relocated to Jamaica, where he worked as a minister in Kingston before his death in 1866. Though little detail exists of his later life and the location of his tombstone is unknown, Ward should be remembered as a dedicated abolitionist whose oratory drew upmost praise from his contemporaries like Frederick Douglass. For historians, Ward’s antislavery career provides fascinating insight into underexplored intersections of religion and race in transatlantic reform networks.

Author’s Bio: Kate Rivington is a PhD candidate in the School of Philosophical, Historical, and International Studies at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia. She completed her MA in history at the University of Melbourne in 2019.

Endnotes

[1] Samuel Ringgold Ward, Autobiography of a Fugitive Negro (London: John Snow, 1855), 245.

[2] Richard J. M. Blackett, Building an Anti-Slavery Wall: Black Americans in the Transatlantic Abolitionist Movement, 1830-1860 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1983), 141.

[3] The Anti-Slavery Reporter, July 1, 1853.

[4] Ward, Autobiography of a Fugitive Negro, 246-249.

[5] “Letter to Parker Pillsbury,” The Liberator, September 15, 1854.