By Hayley Keon

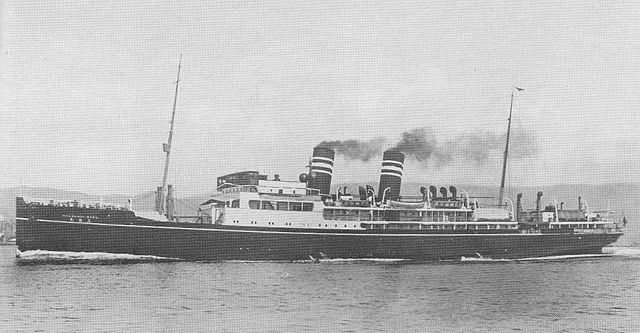

The clouds sat heavy over the harbour but they did little to dampen Louise van Evera’s mood. Writing in her diary on the 19th of November 1927, the twelve-year-old revelled in the day’s excitement, recording in detail the guests and gifts that her family had received as they prepared to depart Shanghai for a four-month journey to the United States.[1] As the daughter of Presbyterian missionaries born in East China, her opportunities to travel beyond the boundaries of the Chinese coastline had been few, but now she faced a journey on a grand scale. Set to tour East and Southeast Asia by steamship, before sailing up the Suez Canal and continuing to Europe via train from Port Said, the itinerary promised a whirlwind tour through southern entrepots. In the process, it traced a line through the burgeoning tourism destinations that had arisen as a result of increasing technological advancement and imperial hegemony in the first half of the twentieth .

But while the prospect of such an adventure seemed appealing at the start of her diary, Louise quickly tired of the ocean’s charms. ‘We’re in the middle of the Indian Ocean + there isn’t much to do,’ she despaired less than two weeks later.[2] To stave off boredom, she noted that she read travel guides and other books, practiced on the ship’s piano, and wrote postcards to friends. In the interim, she would stare out to sea, watching fish leap out of the water. The only activities that seemed to punctuate the monotony on deck for her were the weekly dances for passengers and crew, which provided Louise with opportunities to mix with travellers outside of her age bracket and missionary social circle. After the first of these events, she even in the privacy of her journal that it was ‘the first time I ever danced in my life. It gives you quite a thrill to dance with a skippy French officer.’[3]

Louise’s diary, held at the Presbyterian Historical Society of America in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania is a unique source. As historians like Peter Stearns have noted, primary materials produced by children in historical contexts remain rare discoveries in archives, fuelling the production of histories of childhood that ‘are, on examination, … mainly centred on what adults were doing or saying’ about the lives of young people.[4] This absence can be particularly felt at the intersection of maritime history and histories of empire, which often takes as its source material written accounts created by grown-up travellers, who may have traversed the seas with children but wrote sparingly of their presence there. Partly because of this gap, and partly because of lasting perceptions of seafaring as an inherently masculine and implicitly grown-up endeavour, children rarely feature in published research on steamship travel, leaving much to be explored in relation to their experiences aboard ocean vessels.[5] But, when read alongside other types of sources, texts like Louise’s diary suggest that steamships emerged at the start of the twentieth century as a space where modern childhood could be defined, reinforced, and contested in line with the discourses that circulated the subject on .[6]

Evidence of this coherence can be found in unexpected places. In photographs taken by adults aboard the ships that sailed between Europe and Asia, children appear engaged in activities designed specifically for them, aligning with notions of childhood as a distinct life-stage in which play should be paramount. Moving about the deck, they participated in fancy dress parties, put on performances of fairy plays, and toured the ship’s inner recesses under the care of the captain or crew. On some vessels, specified children’s tables at mealtimes provided planned opportunities for travelling children to meet and build friendships.[7] And as other missionary youths recalled in memoirs, their passages on trans-Pacific liners were filled with race days and sporting competitions stratified by age, as well as frolicking in makeshift swimming pools.[8] All of this suggests that the presence of children shaped steamship entertainment schedules in ways that have often eluded academic assessment.

At the same time however, the liminality of the steamship as a site of mobility challenged some of the standard practices of childhood, particularly within the settler communities of imperial and semi-imperial East Asia. That Louise Van Evera could find herself dancing with an adult sailor suggests that the state of being confined inside the moving vessel allowed for what would otherwise be seen as perilous contact across class lines. e .

Bio:

Hayley Keon is a PhD student in history at the University of Hong Kong, and a recipient of the Hong Kong Research Council’s PhD Fellowship. Her research focusses on the experiences of American missionary youth in treaty port China during the early years of the twentieth century.

[1] L. Van Evera, Diary of Louise Van Evera, unpublished (1927).

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] P. Stearns, ‘Challenges in the History of Childhood,’ 2008, p. 2.

[5] This perception is being thoroughly challenged by scholars writing on maritime history through an array of racial, gendered, class-contingent, and religiously affiliated contexts. For examples, see: E. Robinson Tomsett, Women, Travel and Identity: Journeys by Rail and Sea, 1870-1940, 2017 and S. Crabtree, ‘Navigating Mobility: Gender, Race, and Class at Sea, 1760-1810,’ 2014, p. 89-106.

[6] A full discussion of ‘modern’ childhood lies beyond the purview of this blog. For further reading (particularly in imperial contexts) see: D. Pomfret, Youth and Empire: Trans-Colonial Childhoods in British and French Asia, 2015 and E. Buettner, Empire Families: Britons and Late Imperial India, 2004.

[7] J. Espey, Minor Heresies, Major Departures: A China Mission Boyhood, 1994, p. 81.

[8] Ibid.