By Lauren Brown.

The history of the British Empire has long been framed as a heroic, civilising mission that successfully thrust ‘inferior’ societies into modernity. Thankfully, such rose-tinted nostalgia has begun to fade.

The Mau Mau Rebellion of 1952-1964 was a particularly brutal period of British colonial history. Fed by decades of anger over the British annexation of Kenyan land, the Kikuyu people conducted a series of attacks against British settlers and African colonial ‘loyalists’. The attacks triggered a violent retaliation that saw a ‘pipeline’ of detention camps set up to interrogate, ‘re-educate’ and torture the rebels known as Mau Mau.

Around 80,000 Kikuyu, Embu and Neru Kenyans were incarcerated in the camps.[i] Detainees were aggressively interrogated, thousands were subjected to abuse and several inmates lost their lives. Ex-detainees have listed beatings, whippings and even sexual assault and castration as common occurrences inside what historian Caroline Elkins labelled ‘Britain’s Gulag’.[ii]

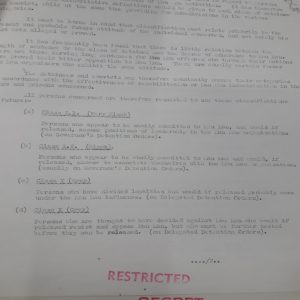

A National Archives document outlining the detainee categories for the screening processes in the camps.

The camps were labelled as centres for rehabilitation. When transferred to a camp, detainees were assessed and categorised into different degrees of ‘Very Black’ to ‘White’. Those labelled ‘Very black’ were seen as degenerative, most devoutly against British rule, and perceived as desperately in need of ‘re-education’. Such prisoners often faced barbaric torture, unsanitary conditions, a lack of food and little hope of freedom.[iii]

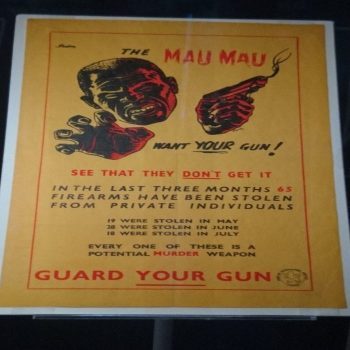

To justify their actions, the British Government instigated their ‘Psychological Warfare’ campaign. Officials could not have the rebellion portrayed as an anti-colonial conflict and thus depicted the Mau Mau as atavistic beasts, incapable of accepting British modernity. Radio broadcasts damning their actions were repeatedly played throughout Kenya, whilst leaflets detailing the Mau Mau warriors’ violent acts were widely distributed.[iv]

The circulation of images of the Mau Mau’s violence justified the use of the camps as part of the government’s attempt to protect Kenya from the Mau Mau.

For decades, the brutality of the detention camps had been buried beneath the public history of the rebellion. However, in 2011, a series of court cases brought the nefarious past of the British Government to light. Former detainees of the Mau Mau camps called for justice from the Foreign Commonwealth Office for the atrocities committed within the camps. The case was staggeringly successful. The former prisoners received compensation, a public apology and even the erection of a memorial in Nairobi, fully paid for by the British Government.

The court cases also instigated the release of thousands of colonial documents, which the British Government had supposedly ‘lost’ at a warehouse in Hanslope Park.[v] It was later revealed that this location held a further 20,000 undisclosed files from 37 former colonies.

It seemed at this point at least, that an era of post-colonial apology, public recognition and governmental decency had been born. However, since 2018, it appears hopes of such a revolution have diminished.

In 2018, 40,000 Kenyans descended on the English courts seeking damages for the sufferings they had endured within the detention camps. Files held in the British National Archives explicitly detail the horrific conditions of the camps with prisoners writing to local government representatives complaining of squalor, a lack of food and corporal punishment.

However, the Kimathi & Others v The Foreign and Commonwealth Office (2018) case was dismissed under the notion that a fair trial was not possible because of the 50-year delay. Justice Stewart J, the High Court judge who dismissed it, argued that there was a lack of ‘clear’ evidence.[vi]

However, the defendants were prevented from lodging the case before 2011 because of the British Government’s hidden tranche of colonial documents. As they are now available for consultation, they could be utilised in a trial. Nevertheless, the damage appears to be done, as their concealment prevented earlier claims from being made.

How can these people obtain justice if their claims are dismissed due to the passage of time? How can this be just when the British Government had systematically hidden such evidence to prevent knowledge of its crimes?

In 2012, it was made clear that the British Government felt it had done enough. Upon the day of the monetary settlement, former UK Foreign Secretary William Hague stated that the British government did not believe that the settlement ‘established a precedent’. In this statement, the UK Government made it clear that it would not entertain any further attempts to obtain justice for sufferings endured under the British Empire.

All of this should be remembered when the current British Government voices its support for the Black Lives Matter Movement. A hollow gesture, when that same government maintains such a self-righteous narrative of Britain’s imperial legacy, in defiance of those who continue to live with its consequences.

Author’s Bio:

Lauren Brown has an MA and MLitt in History from the University of Dundee. She has multiple publications on Kenyan history, particularly focused on the Mau Mau Rebellion. Lauren is currently the assistant editor for Scottish Financial News and Scottish Housing News.

Twitter – @LaurenBroon

References:

Images: Author’s own.

[i] Caroline Elkins, Imperial Reckoning: The Untold Story of Britain’s Gulag in Kenya (Henry Holt and Company: New York, 2005) p. xii.

[ii] Caroline Elkins, Imperial Reckoning: The Untold Story of Britain’s Gulag in Kenya, p.209.

[iii] British National Archives, WO276428, Memorandum from Kenya Major General titled: ‘Screening Categories’, 21/12/1954.

[iv] British National Archives, FCO141/6227, ‘The World of Today, Oct 11 1958: Broadcast from West Kenya Radio’, Radio Broadcast, 11/10/58.

[v] David M Anderson, ‘Mau Mau in the High Court and the ‘Lost’ British Empire Archives: Colonial Conspiracy or Bureaucratic Bungle?’ The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, Vol 39, Issue 5, (Routledge: London and New York, 2011).

[vi] Casemine, Kimathi & Ors V The Foreign and Commonwealth Office, Casemine.com, https://www.casemine.com/judgement/uk/5b6401a42c94e04659e5effc, ND, accessed: 08/03/2020.

Recommended Reading List:

- Anderson, David, Histories of the Hanged: Britain’s Dirty War in Kenya and the End of Empire (Weidenfield & Nicholson Publishing: London, 2005).

- Badger, Antony, ‘Historians, A Legacy of Suspicion and the ‘Migrated Archives’, Small Wars & Insurgencies, Vol 23, Issue 4-5 (Taylor and Francis Publishing: London and New York, 2012).

- Cooper, Frederick, ‘Mau Mau and the Discourses of Decolonization,‘ Journal of African History, Vol 29, Issue 2 (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1988).

- Elkins, Caroline, Imperial Reckoning: The Untold Story of Britain’s Gulag in Kenya (Henry Holt and Company: New York, 2005).

- MacArthur, Julie (editor), Dedan Kimathi on Trial: Colonial Justice and Popular Memory in Kenya’s Mau Mau Rebellion (Ohio University Press, Athens, 2017).