By Jessica A. Fernández de Lara Harada

Mexico and Japan share histories of empire and colonisation. Formerly known as New Spain, Mexico was colonised by Spain from 1521 to 1821 and, after independence, the US occupied half of its territory and gradually increased its economic and military influence. Following 250 years of self-isolation, in 1854 Japan was forced by the US and other European powers into informal imperialism through unequal and non-reciprocal treaties. After the Second World War, the US occupied part of Japan’s territory and controlled crucial aspects of its government. It is often argued that Japan sought to emulate Western powers in their imperialist pursuits to challenge western hegemony, and occupied parts of East Asian territories during the first half of the twentieth century. It is less known, however, that Mexico became an empire within its territory and acted as the metropole of the Philippines which facilitated Mexico’s importation of enslaved Asians through the Pacific Ocean. For centuries, Mexican ruling elites sought to conquer China and Japan (Gruzinski 2014), and among these elites there has coexisted admiration, fear and envy for Japan’s resistance to submit to the fate of the “New World”.

This essay reflects on how to bridge global and local dynamics between two relatively peripheral countries in discussions of contemporary migration amidst legacies of imperialism and colonialism. It examines the particular histories of people to better understand the dynamics of industrial capitalism and movements of labour at specific times. I argue that Mexicans of Japanese descent resist their subjugation by claiming an identity rooted in a familial attachment to their ancestors’ home that allows them to reconcile their difference and carve out a sense of belonging in Mexico. In what follows, I first locate the historical position of Japanese in Mexico’s racial formations. Then I show how their ascription has generally oscillated from bodies of labour to contained bodies as further elaborated below. I conclude by presenting “unforgetting” as a form of resistance against the racial project of mestizaje.

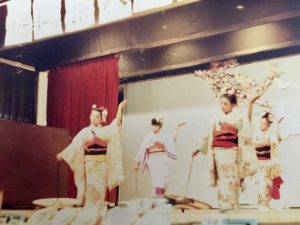

“Photo 1. Women dancing at the Mexican Japanese Cultural Centre (日墨文化会館) in Mexico City in the 1980s. Personal archive.”

At least since the Iberian conquest in 1492, Asia has been pivotal in the historical conceptualization and material invention of the Americas. From 1565 to 1815, the Manila-Acapulco Galleon Trade Route ushered in 250 years of continued global interactions, through which Mexico laid claim to its global centrality and superiority over Asia. This involved a multidirectional movement of ideas, objects and people. In this period, the first wave of Asian immigrants to Mexico came from China, Japan and other Southeast Asian Kingdoms (Slack Jr., 2009). These early population movements included merchants, seafarers, slaves, servants, and free migrants. It is difficult to establish how they were categorised. However, most historians agree that despite their rather different provenance, Asians were generally lumped together under the term “chinos”.

Beltrán (1944) shows that in sixteenth-century Mexico ‘chinos’ were ‘Negroes’ or slaves from the Philippines traded upon their arrival in Acapulco. Seijas (2014) clarifies that the term ‘chino’ was used only for individuals from Asia who came to the Americas as slaves. This author shows that for sixteenth and seventeenth-century contemporaries, social identities depended more on legal status within the empire than on visible racialised categories. Consequently, “[u]nable to depend on color or other physical markers, masters used face brands to segregate chino slaves from the free Indian population”, while African slaves were marked on the chest or arm (Seijas, 2014: 165). Significantly, by the end of the seventeenth century, ‘chino’ slaves were liberated and rendered indigenous vassals to the crown (Seijas 2016). However, Slack Jr. (2009: 22) notes that with racial blending the insertion of ‘chinos’ metamorphosised and “[o]rientals were grouped together with negros and mulatos” in the lower caste in juridical and practical instances until the turn of the eighteenth century. Importantly, Carrillo Martín (2015: 109) argues that “in the eyes of other people in New Spain there was no substantial difference between them [Japanese] and other chinos”; most were treated as chinos, although a few gained social distinction by having wealth or experiences as soldiers.

“Photo 2. Daruma. Personal Archive”

From the mid-nineteenth to the mid-twentieth centuries, Asian forced labour and free migration to the Americas became more differentiated. In the early twentieth century, some Mexican intellectuals emphasized the desirability of Japanese over the Chinese for labour migration due to the former’s docility, industry, and hard-work while the Japanese state was deemed a model to which Mexico should aspire. The 1888 Treaty between Japan and Mexico was their third major formal contact, following the 1609 and 1842 initiatives, and facilitated state-sponsored migration. Between 1897 and 1942, 14,667 Japanese migrants arrived in Mexico (Ota Mishima, 1997). Most of them came from southwestern and semi-colonial regions of Japan. They were brought as bodies of labour for plantation fields, railroad constructions and mines, and were made contained bodies by American anti-Japanese exclusion. The 1906 Gentlemen’s Agreement cut-off Japanese migration to Mexico, while racism and exclusionary informal practices decreased the movement and growth of this population. Mexico replicated US policies in response to economic rivalry and geopolitical interests. Mexican governing elites feared that Japanese immigrants could contest their authority and power, but veiled their anti-Japanese racism to avoid infringing their 1888 Treaty and appear overtly aggressive for Japan was considered a potential ally to counter the US hegemony.

However, Mexican post-revolutionary nationalism (1910-1924) developed on the basis of anti-Asian racism, which shaped Mexican restrictive immigration laws (Székely, 1993: 151), and again “Japanese immigrants were more often than not lumped together with the Chinese in anti-Asian campaigns throughout the 1920s and 1930s”. (Chang, 2011: 356). This xenophobic nationalism cemented the racial ideology of mestizaje, which promoted the assimilation of indigenous peoples into European ideals of whiteness and only recognised this Euro-Amerindian (‘racial’, religious and cultural) mixing as authentic Mexican. In this period, the Mexican government began to register, classify and charge fees to Japanese migrants as foreign aliens of the yellow race. Towards 1937, nationalist movements allowed unions and other people to arbitrarily seize immigrants’ properties. This hostility gradually reached an endpoint in the second world war when Mexico declared war against Japan and ordered the forced displacement, dispossession and containment of people of Japanese descent. Even though some were Mexican by birth or naturalisation, Mexican Japanese families were treated as a national threat based on their ethno-racial origin, and this racism spurred state brutality with lasting repercussions.

Photo 3. The author’s fieldwork research with the Mexican Japanese community that lives and works in the Mines ‘Las Esperanzas’, in Coahuila, México.

The racial project of ‘mestizaje’ relies as much on assimilation into whiteness as on reproducing expendable bodies. Mestizaje (re)creates racial infrastructures that operate through immigration and demographic controls. Due to the workplaces they occupied upon arrival, many Japanese migrants married indigenous and black populations. This accelerated their incorporation into the lower stratum of the racial hierarchy. As I have observed throughout my research, despite attempts at erasure and elimination, many Mexicans of Japanese descent refuse forgetting and seek to unbury their family histories. This reconciliation is being achieved in the US through the Redress Movement and the Civil Liberties Act won by Japanese American communities in the 1980s and 1990s, and in parts of Latin America where the Peruvian and Brazilian governments have formally apologised for the violations of rights of their citizens of Japanese origin.

Thus, there is much work to do in Mexico to eradicate anti-Asian racism, repair the damages, and remove the stigma from these ethno-racial minority groups. It is only by doing so that we can dismantle racism, eradicate ethno-racial violence and attain equality and justice for all.

Author’s Bio: Jessica A. Fernández de Lara Harada is a PhD Candidate and Gates Scholar in the Centre of Latin American Studies at the University of Cambridge. Her research focuses on the racist logics of mestizaje, the experiences of Mexicans of Japanese descent, and the process of claiming histories of exclusion and repairing injustices. Her research interests include the history of race relations, legacies of transpacific migrations, and nation-state formation in contemporary Mexico.

Title Images

Photo 1. Mr. José Chotiro Yokoyama, naturalised Mexican, arrested with his family by Mexican government authorities on 10th February 1943. Their fate is unknown from the records. AGN 2-1/362.4(52)/195.

Photo 2. Mr. José Chotiro Yokoyama with his wife Mrs. Umeyo Okamoto, both naturalised Mexican, and their children Micko and Yoshiko Yokoyama, who were born in Mexico, arrested by Mexican authorities on 10th February 1943. Their fate is unknown from the records. AGN 2-1/362.4(52)/195.

References

Aguirre Beltrán, G. (1944) The Slave Trade in Mexico, The Hispanic American Historical Review, 24(3): 412-431.

Carrillo Martín, R. (2015). Asians to New Spain: Asian cultural migratory flows in Mexico in the early stages of “globalization” (1565-1816). Internet Interdisciplinary Institute, Universitat Oberta de Catalunya, PhD in Information and Knowledge Society.

Chang, J. O. (2011). Racial alterity in the Mestizo Nation, Journal of Asian American Studies, 14(3): 331-359.

Gruzinski, S. (2014). The Eagle and the Dragon: Globalization and European Dreams of Conquest in China and America in the Sixteenth Century, translated by Jean Birell, Malden, MA : Polity Press.

Ota Mishima, M.E. (1997) Destino México: Un estudio de las migraciones Asiáticas a México, siglos XIX y XX, México: El Colegio de México.

Seijas, T. (2014) Asian Slaves in Colonial Mexico: From Chinos to Indians, Cambridge University Press.

Seijas, T. (2016). Asian migrations to Latin America in the Pacific World, 16th–19th centuries, History Compass, pp. 573-581.

Slack Jr. E.R. (2009) Signifying New Spain: Cathay’s Influence on Colonial Mexico via the Nao de China, Journal of Chinese Overseas, 5(1): 5-27.

Székely, G. (1993) Mexico’s International Strategy: Looking East and North, in C. Székely, and B. Stallings (eds.) Japan, the United States, and Latin America: Toward a Trilateral Relationship in the Western Hemisphere, Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Further reading

FitzGerald, D.S. (2014) Culling the Masses: The Democratic Origins of Racist Immigration Policy in the Americas, Cambridge, MA : Harvard University Press.

Knauth, Lothar (1972) Confrontación Transpacífica. El Japón y el Nuevo Mundo Hispánico, 1542—1639, México: UNAM, Herman Melville.