By Anna Nicol.

Art frequently operates as a “vehicle of memory”, adding tangibility to past events. Sociologist Elizabeth Jelin coined the phrase to refer to how cultural products connect ‘individual subjectivities, societal or collective belonging, and the embodiment of the past.’[1] Artistic mediums are particularly innovative at creating space for counter-memories and marginalised narratives under oppressive political regimes, especially in countries such as Chile where there are competing narratives regarding the recent past.

On 11 September 1973, the Chilean Air Force bombed La Moneda Palace; declaring a military coup against Salvador Allende’s presidency and establishing General Augusto Pinochet’s seventeen-year rule. The military government aimed to transform Chilean society, reversing the left-wing reforms of Allende’s Unidad Popular, privatising state-led enterprises and the healthcare system, and implementing laws “protecting” national security.[2] Pinochet’s reforms held two key components: national security measures and pro-birth policies to uphold the Patria, both of which were subsequently ratified in the 1980 constitution.[3]

By claiming Chile to be on the brink of chaos as a result of socialist reforms and values, Pinochet was welcomed by middle-class and military families. Contrastingly, Chileans who the government labelled as “subversive” were imprisoned, tortured and murdered. According to official reports 2,279 people were disappeared during military rule.[4] The stark contrast between believing the coup to have “saved” Chile and the reality for impoverished and persecuted communities created a division within Chilean society both at the time and in the collective memory of the period.

Pinochet’s new policies relied on traditional and conservative gender norms in order to curtail personal freedoms. Implementing gendered policies meant creating the framework for the “ideal” Chilean as a mould to aspire to and uphold the government; creating divides between actors in the public and private spheres and controlling people’s bodies. Controlling bodies and their presentation meant the regime’s control pervaded the personal intricacies of individuals’ lives including dress, behaviour and personal relationships. Gender theorist Judith Butler argues that it is impossible to distinguish gender from ‘the political and cultural intersections in which it is invariably produced and maintained.’[5] Therefore, the regime policies targeting gender moulded national “permissible” conceptions of masculinity and femininity, and infringed on individuals’ autonomy over their bodies and their identities.

Consequently, to live openly outside of rigid gender norms was difficult and required underground political work in order to create space for individuality and community in the face of repression. Artistic mediums, such as photography, literature and folk art, were one such way to construct alternative narratives and memories to those the regime promoted and its supporters. Photography is commonly associated with memory: a photograph captures a moment in time and freezes it for beyond that point. The visuality of a photograph, moreover, acts as a form of evidence by pinpointing and cementing the moment in time that an individual or group existed.

Between 1982 and 1987 photographer Paz Errázuriz and journalist Claudia Donoso compiled photographs and testimonio (testimonial literature) of a group of travesti prostitutes living in Talca and Santiago. The Spanish travesti directly translated into English means “transvestite”, an outdated term now more commonly referred to as a cross-dresser. However, travesti is not simply used to describe cross-dressing, nor transgender, its definition is more gender variant in that the gender identity of each travesti fluctuates depending on the individual. Paz Errázuriz’ book La Manzana de Adán (“Adam’s Apple”) is a photographic essay not only detailing how working-class queer groups endured oppression, but also showcasing the complexities of individual gender identity in the face of repression.

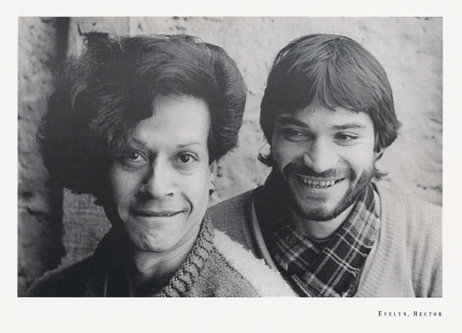

La Manzana de Adán combined both documentary photography and portraiture. While photos do not necessarily provide the same information as a written source, they can still help us to explore memory and queer identities in the face of persecution. The below photograph is a portrait of travesti, Evelyn and her partner Héctor. Photographing Evelyn in casual clothes, compared to other photos in the series of her in full drag, documented her ability to traverse the gender binary. Her identity was multifaceted and involved both her proximity to femininity and her identity outside that femininity. Producing portraits facilitates ‘contending social classes [claiming] presence in representation.’[6] Therefore, including intimate portraits of Evelyn both in drag and in her usual clothes asserted her presence as a genderqueer individual living under a regime that actively sought to suppress gender identities that deviated from and undermined traditional gender norms.

Evelyn and Héctor. La Manzana de Adán, Paz Errázuriz. 1984.

Furthermore, the photo normalises Evelyn and Héctor’s queer relationship. Historically, portrait photography increased the accessibility of the art to the general public as amateur photographers were able to document family and friends.[7] This intimate photo therefore demonstrates how portraiture bridges the public and private spheres: you are just as likely to see this kind of portrait in a photo album as you are in an art gallery. It evidenced the familiarity and existence of personal relationships that the government deemed “subversive.” Moreover, Donoso’s accompanying documentation of their conversations further countered the one-dimensional view of masculinity and male sexuality the regime promoted. For example, Héctor described how ‘many people think [a homosexual relationship] is somehow different, it isn’t really’ – they were passionate and argued with each other; highlighting how the tension within homosexual relationships were similar to those in heterosexual relationships.[8] Additionally, Evelyn revealed that when she was briefly in jail Héctor was in a relationship with a woman before resuming their relationship upon Evelyn’s release.[9] We can speculate on how Héctor would label his sexuality but the photo documenting their relationship and accompanying testimonio proved that masculinity and male sexuality were more nuanced than the regime claimed them to be.

The photos in La Manzana de Adán acted as vehicles of memory; counteracting dictatorial rhetoric that promoted heteronormativity and conservative gender ideals. Capturing the memories of queerness meant that Errázuriz, Donoso and the travesti subverted the gender binary and claimed space in the collective memory of Chilean identity during Pinochet’s regime.

Author’s Bio: Anna has just completed a MSc in Contemporary History at the University of Edinburgh. Her research interests focus on gender, sexuality and memory in late-twentieth century Latin America.

NB: This post is based on the arguments from Anna’s MSc dissertation “‘You Earn More With Your Body:’ Gendered Power in the Memories of Pinochet’s Chile,” August 2020.

Selected Further Reading

Balderston, D. & D. J. Guy, Sex and Sexuality in Latin America: An Interdisciplinary Reader, New York: New York University Press, 1997.

Gómez-Barris, M. Beyond the Pink Tide: Art and Political Undercurrents in the Americas, California: University of California Press, 2018.

Lancaster, R. N. Life is Hard: Machismo, Danger, and Intimacy of Power in Nicaragua, London: University of California Press, 1994.

Stern, S. J. Remembering Pinochet’s Chile: On the Eve of London 1998¸ Durham: Duke University Press, 2004.

Taylor, D. Disappearing Acts: Spectacles of Gender and Nationalism in Argentina’s “Dirty War”, London: Duke University Press, 1997.

Endnotes

[1] E. Jelin, “Public Memorialization in Perspective: Truth, Justice and Memory of Past Repression in the Southern Cone of South America”, International Journal of Transitional Justice, 1, 2007, 141.

[2] M. E. Acuña Moenne, trans. Matthew Webb. “embodying memory: women and the legacy of the military government in Chile”, Feminist Review, 151.

[3] Ibid, 154.

[4] L. Baldez, Why Women Protest: Women’s Movements in Chile, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010) 133.

[5] J. Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity, (London: Routledge, 1990) 3.

[6] J. Tagg, The Burden of Representation: Essays on Photographies and Histories, (London: Macmillan, 1988) 18.

[7] Ibid.

[8] P. Errázuriz & C. Donoso, La Manzana de Adán, trans. G. Donoso Yañez, (Santiago: Zona Editorial, 1990) 116.

[9] Ibid, 114.