By Lauren Brown.

‘To the people death knows no colour, and, as such, rates of pay should be adjusted in that spirit.’[i] This statement, featured in the West African Pilot in 1941, encapsulates a key issue faced by British African soldiers who fought during the Second World War. It is an issue that has still not been rectified. Unfortunately, Africans have been grossly underrepresented in official histories of WWII, so while many went under paid, more have been forgotten altogether. From 1939 -1945, some 15,000 African soldiers lost their lives fighting for Britain.

While the British population widely remembers and commemorates the sacrifices of British soldiers throughout the conflict, the contribution of colonial African soldiers has often slid under the radar. However, the problem does not end here. After the war, thousands of East African soldiers did not receive payment for their service or found that they had been paid much less than expected. Upon returning from active service in the Burma campaign (1941-45), Eusebio Mbiuki – a Kenyan veteran who was enrolled in the King’s African Rifles – found that his service payment, known as war gratuity, was significantly lower than the payment for white soldiers.[ii]

Last year, a document found in the British archives revealed African soldiers who served in the British Army during WWII were paid as much as three times less than their white counterparts. Several MPS called for an official enquiry while Lord Richard Dannatt, former head of the British Army, urged the government to provide compensation to the veterans affected by the inequality.[iii] An enquiry was not launched. Such inaction is a disservice to the masses of Africans who fought and laboured for the freedom of their colonial overlords when they themselves were not free.

Over the course of the conflict, almost one million African soldiers from British, French, Italian and Belgian colonies contributed to the war effort, with soldiers from South Africa also employed in military action.[iv] Much like their European comrades, African servicemen put their lives at risk to fight for the freedom of the West. Those not engaged in active combat greased the war machine, becoming labourers, porters, carriers, cooks and mechanics.[v] African servicemen received training in mechanical work, carpentry and joinery. They learned how to use mortars and machine guns, how to become signalers, drivers and medical orderlies. African cities and towns became more industrialised as thousands laboured to provide ammunition, food and mineral supplies.[vi] Without these vital activities of the African colonial subjects, the British metropole and its deployed armies would have faltered.

Regardless of their momentous input into the global war effort, the UK government has refused to honour its colonial veterans with the appropriate compensation and public recognition for their service. However, this is a precedent which was set upon the victory of the allied powers during the war. British African servicemen have not just been forgotten. The British state deliberately downplayed the contribution of colonial soldiers during the WWII to quash demands for the post-war social, economic and political changes that would call the entire structure of British colonial society into question.

The British Government’s demobilisation strategies for colonies, such as Kenya, sought to revert any socio-economic progress made within African communities. Despite the rhetoric of wartime recruitment in Kenya, African soldiers came home to few employment opportunities, little social mobility, unpaid wages and often with injuries for which they received poor medical care and rehabilitation.

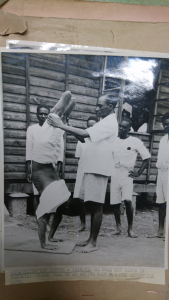

Image 2: WWII veterans at a rehabilitation centre in Nairobi, Kenya.

The post-war demobilisation strategies aimed to quell calls for societal changes born from the wartime rhetoric of anti-fascism and freedom. Returning soldiers wanted to use their newly acquired skills to obtain better jobs away from their agricultural homesteads. Many returning African soldiers wanted to use their new skills to obtain clerical jobs in local government or open local businesses and stores.[vii]However, while there were limited opportunities for post-war training and further education, British Government documents have revealed that only the most skilled African soldiers would be considered for such privileges upon demobilisation.

A pamphlet discussing post-war employment stated that the government wanted to provide ‘the best of the army tradesmen’ with further training to ‘make them suitable as peace-time tradesmen’.[viii] However, it urged that there was ‘no use giving this further training to any but the best’ due to the lack of positions available.

Thousands of African soldiers were educated by the British Army during the war, providing many with an education outside of the colonial mission schools located across the continent. African soldiers deployed in other colonies, such as India, also returned home with knowledge of the world outside of Africa and no longer wished to be suppressed by the boundaries of pre-war colonial society.

Many askaris expected the British Army to support them and act as a ‘source of patronage’ after the war. They expected pensions and gratuity pay alongside other rewards for service, with many returning soldiers arguing that wartime propaganda made such promises. Liaison officers warned officials in Kenya that African soldiers were expecting a grant of land or similar rewards for their service. In an attempt to eradicate such desires, British officials utilised various methods to remove the belief that returning servicemen were due tangible rewards for their labours.

In August 1945, propaganda guidelines were issued for officers preparing to give lectures to East African soldiers awaiting demobilisation. These documents explicitly dealt with the ‘correction of the soldier’s perspective’ on their war effort. Officials stressed to African servicemen that their reward was the victory of the allied forces and the destruction of Nazi fascism.[ix]

The mass migration of demobilised Kenyan soldiers and trained workers into the mainstream labour market in Kenya would have irreparably altered colonial society throwing British colonial hegemony into disarray. In an attempt to channel the returning African soldiers back into their pre-war agricultural employment, the British government directly told Kenyan soldiers that agricultural work was the only secure employment available to them after demobilisation.[x] Clearly, the British government tried to convince Africans that seeking further training was not worth their while. Therefore, it is evident that the demobilisation strategies of the British government were an extension of the pre-existing colonial apparatus which restricted the liberty and prosperity of Africans decades before the war.

The forgetting of African soldiers from the public history of the WWII was not accidental. It was an outcome actively sought by the British Government and therefore, actions should be taken to ensure their contribution to the global allied war effort is not forgotten. On VE day this year, Jaston Khosa, one of the last veterans of Britain’s colonial army who served in the Northern Rhodesia Regiment, was buried. His words in an interview last year encapsulate the collective experience of British and African soldiers during WWII that have been overshadowed by Eurocentric retellings of the history. He said: “British and ourselves, we suffered together.”[xi] Therefore, as Britons don their poppies and bow their heads in silence this year, it is imperative that we remember those African soldiers who have been forgotten from the history of WWII. Even more importantly, efforts should be made to compensate and accommodate those African veterans still alive today, who have not yet been properly recognised or repaid for their sacrifices made during the war.

Author’s Bio:

Lauren Brown has an MA and MLitt in History from the University of Dundee. She has multiple publications on Kenyan history, particularly focused on the Mau Mau Rebellion. Lauren is currently the assistant editor for Scottish Financial News and Scottish Housing News.

Twitter – @LaurenBroon

Suggested reading list:

- Katrin Bromber, ‘Part Two: Correcting Their Perspective: Out of Area Deployment and the Swahili Military Press in World War II’, in:The World and World Wars: Experiences, Perception and Perspectives from Africa and Asia, Heike Liebau (Brill: The Netherlands, 2010).

- Fay Gadsden, Wartime Propaganda in Kenya: The Kenya Information Office, 1939-1945, The International Journal of African Historical Studies, Vol 19, No.3 (Boston University African Studies Press: Massachusetts: 1986).

- David Killingray, Fighting for Britain: African Soldiers in the Second World (James Currey Publishing: Suffolk, 2012).

- Timothy H. Parsons, The African Rank and File: Social Implications of Colonial Military Service in the King’s African Rifles, 1902-1964 (Heinemann: New Hampshire, 1999).

- Judith A. Byfield, Africa and World War II (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2015)

References:

[i] G.O Olusanya, The Role of Ex-Servicemen in Nigerian Politics, The Journal of Modern African Studies, Vol.6, No.2 (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1968) p.233.

[ii] Jack Losh, ‘We were abandoned: the Kenyan soldier forgotten by Britain’, The Guardian, 13th Feb 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/feb/13/we-were-abandoned-the-kenyan-soldier-forgotten-by-britain. Accessed: 25/10/2020.

[iii] Jack Losh, ‘Ex-head of British army backs compensation for African WWII veterans, The Guardian, 1st March 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/mar/01/ex-head-of-british-army-backs-compensation-for-african-wwii-veterans. Accessed: 25/10/2020.

[iv] David Killingray, Fighting for Britain: African Soldiers in the Second World (James Currey Publishing: Suffolk, 2012) p.8.

[v] Ibid, p.64.

[vi] Judith A. Byfield, Africa and World War II (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2015) p.24; Ashley Jackson, Supplying War: The High Commission Territories’ Military-Logistical Contribution in the Second World War, Journal of Military History, Vol 66. No. 3, 2002, p.720.

[vii] David Killingray, Fighting for Britain: African Soldiers in the Second World, p.95.

[viii] TNA, CO822/118/6, ‘Post-War Employment and Training of African Ex-Servicemen, Current Affairs Pamphlet: ‘Training and Employment, Monthly Publication by The East Africa Command, No,24, African Edition, Printed by Printing and Stationary Services East Africa Command for the Directorate of Education and Welfare’.

[ix] Katrin Bromber, Correcting their Perspective: Out of Area Deployment and the Swahili Military Press in World War II, in The World and World Wars: Experiences, Perception and Perspectives from Africa and Asia, Heike Liebau (Brill: The Netherlands, 2010). p.280.

[x] TNA, CO822/118/6, ‘Post-War Employment and Training of African Ex-Servicemen’, Current Affairs Pamphlet: ‘Training and Employment’, ;Kenya: Central Employment Bureau’, Monthly Publication by The East Africa Command, No,24, African Edition, Printed by Printing and Stationary Services East Africa Command for the Directorate of Education and Welfare’.

[xi] Jack Losh, ‘You are still a soldier to me’: the forgotten African hero of Britain’s colonial army, The Guardian, 10th May 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2020/may/10/you-are-still-a-soldier-to-me-the-forgotten-african-hero-of-britains-colonial-army. Accessed: 25/10/2020.5/10/2020.

[ix] Katrin Bromber, Correcting their Perspective: Out of Area Deployment and the Swahili Military Press in World War II, in The World and World Wars: Experiences, Perception and Perspectives from Africa and Asia, Heike Liebau (Brill: The Netherlands, 2010). p.280.

[x] TNA, CO822/118/6, ‘Post-War Employment and Training of African Ex-Servicemen’, Current Affairs Pamphlet: ‘Training and Employment’, ;Kenya: Central Employment Bureau’, Monthly Publication by The East Africa Command, No,24, African Edition, Printed by Printing and Stationary Services East Africa Command for the Directorate of Education and Welfare’.

[xi] Jack Losh, ‘You are still a soldier to me’: the forgotten African hero of Britain’s colonial army, The Guardian, 10th May 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2020/may/10/you-are-still-a-soldier-to-me-the-forgotten-african-hero-of-britains-colonial-army. Accessed: 25/10/2020.

Images:

- THE KING’S AFRICAN RIFLES IN EAST AFRICA, 1941 (E 1968) Soldiers of the King’s African Rifles (KAR) during the British advance into Italian Somaliland. Copyright: © IWM. Original Source: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205126438

- Author’s own image.