By Austin Clements. Twitter: @ClementsAustinJ

In the American mind, the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) was a romantic adventure. Idolized in novels and film, such as Ernest Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls and popular non-fiction such as Adam Hochschild’s Spain in Our Hearts, brave Americans defied their nation’s craven neutrality to embark on a noble crusade against fascism. So ubiquitous is the notion of heroic “premature antifascism” that one cannot be faulted for believing most Americans supported the Second Republic of Spain and its Loyalist Defenders against the Nationalist aggressors, led by the aspiring fascist dictator Francisco Franco. Seven months after German and Italian fascist troops airlifted Franco’s forces from Morocco into mainland Spain to wage a civil war, a Gallup poll reported only a minority of Americans (22%) supporting the Republican Loyalists. 66$ did not favor either side. The remaining 12%—roughly one in eight Americans—supported the fascist-backed Franco and the Movimiento Nacional.[1]

Who were these Americans, and why did they support an authoritarian dictator? Fortunately for historians, pro-Franco Americans were prolific, producing dozens of pamphlets, books, magazines, lectures, and sermons defending and elucidating their support for General Franco against what they perceived as a malicious communist enemy. Most of the publications came from American Catholic organizations, written and distributed by laypersons and the hierarchy alike. Catholics around the globe had for years been primed to see communism as an existential threat to Christianity. The establishment of the Second Republic, followed by the ransacking of churches and murder of Catholic clergy, nuns, and laity, convinced Catholics all over the world that the new Spanish government was illegitimate, dominated by radical Leftist factions pledging fealty to the Soviet Union.

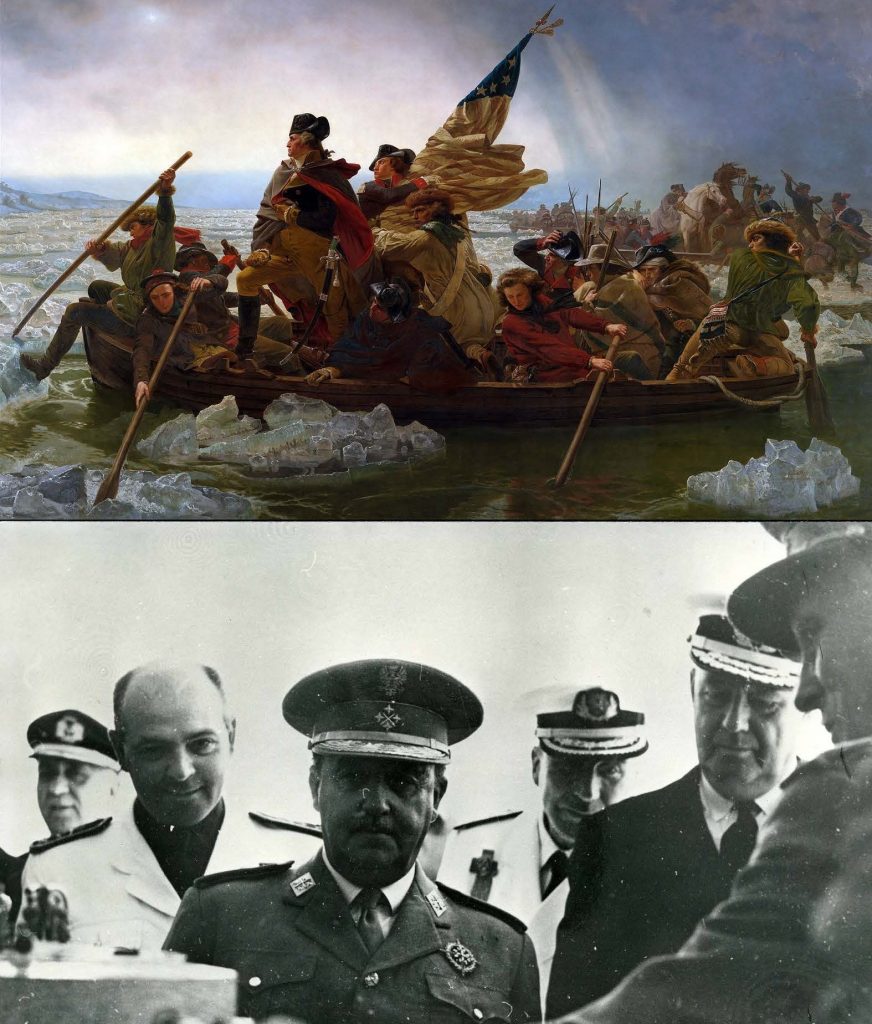

To the millions of pro-Nationalist Americans, Franco was not committing a fascist coup against a liberal democracy but leading a counter-revolution against an insidious foreign enemy—communism—pulling the Spanish Republic’s strings from Moscow. The Nationalists were not fascists, they argued, but Spanish patriots restoring Christianity, the rule of law, and the will of the people. American pro-Nationalists therefore likened General Franco to General Washington leading an assault against a tyrannical foreign power: now Reds rather than Redcoats.

Allusions to Washington and the American Revolution abounded in pro-Nationalist literature. Labelled derisively by Loyalists as “rebels” against a democratic government, Nationalists and their supporters donned the insult as a badge of honor. “Occasions there have been in human history—and 1776 is one of them,” one pamphleteer wrote, “when men who are called rebels are the custodians of liberty and national honor.”[2] George Washington was such a person: “he was a rebel against the legitimate government of England. Yet he did right. We are proud of him!”[3] Repudiating the “fascist” label for Franco, the conservative cultural critic H.L. Mencken claimed the Spanish general was “no more an agent of Hitler and Mussolini than Washington was an agent of Louis XVI.”[4] Americans should support Franco, this argument went, because like Washington he sought only independence from a tyrannical alien foe.

As a war for independence, pro-Franco Americans argued, the Spanish Civil War should be celebrated as the Spanish Fourth of July. In the not-too-distant past the Spanish Empire had aided the American Revolution, one pro-Franco magazine postulated, supplying gold and guns to the nation struggling to be born.[5] The political myths surrounding Washington and Franco therefore suggested an interconnected past, present, and future between America and Spain. Franco’s rebellion was “another chapter in the history of the United States,” one writer argued, for the Spanish General, by halting the spread of communism at the Pyrenees, had rescued the American way of life.[6] A modern George Washington, Franco was the savior of both “Mother Spain and our civilization from chaos and barbarism.”[7] In likening Franco to Washington, the Spanish general’s American admirers painted the fascistic Nationalist rebellion as patriotic, democratic, and just—and in the process transformed their own support for Franco into defense of “Americanism.”

The association between “Americanism” and anti-communism survived the victory of the Movimiento Nacional in 1939 and the defeat of Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany in 1945. Indeed, Francoist Spain’s neutrality during World War II confirmed for American apologists that Franco was no fascist. In the climate of the Cold War, the virulent anti-communism undergirding the pro-Franco argument came to overshadow its advocacy for fascistic authoritarianism. The language of patriotism against an insidious communist foe survived even the collapse of the Soviet Union, coloring Right-wing and conservative rhetoric to this day. Most recently, the Americans encouraged by the sitting president to attack the Capitol on 6 January 2021 envisioned themselves as true patriots and saviors of civilization from radical Leftism and a stolen election. The national symbols stitched and tattooed on the flags, clothes, and bodies of the insurrectionists storming the Capitol adorned the pages and colored the rhetoric of pro-Franco literature eighty years before.[8] The violent reactionaries called upon the ghost of George Washington once more to lead a rebellion against an illegitimate government—this time, the very one the American general had himself fought to establish.

Author’s Bio: Austin Clements is a Ph.D. student in the Department of History at Stanford University. His area of focus is the United States in the 20th century, specifically the relationship between religion and politics in the interwar period. His current research investigates the implications of Christian belief systems and their interactions with political ideologies at home and abroad, looking at fascism, antisemitism, communism, and nationalism.

Further reading:

Casanova, Julián. A Short History of the Spanish Civil War. London: I.B. Tauris & Co, 2013.

Chamedes, Giuliana. A Twentieth-Century Crusade: The Vatican’s Battle to Remake Christian Europe. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2019.

Chapman, Michael E. Arguing Americanism: Franco Lobbyists, Roosevelt’s Foreign Policy, and the Spanish Civil War. Kent, OH: The Kent State University Press, 2011.

Chappel, James. Catholic Modern: The Challenge of Totalitarianism and the Remaking of the Church. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2018.

O’Toole, James. The Faithful: A History of Catholics in America. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2010.

Vincent, Mary. Catholicism in the Second Spanish Republic: Religion and Politics in Salamanca, 1930-1936. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996.

Endnotes

[1] George H. Gallup, The Gallup Poll: Public Opinion, 1935-1971 (New York: Random House, 1972), 1:49.

[2] Aurelio M. Espinosa, The Spanish Republic and the Causes of the Counter-Revolution (San Francisco: The Spanish Relief Committee of San Francisco, 1937), Hoover Institution Library Pamphlet Collection, NX4330, Hoover Institution Library.

[3] Umberto Olivieri, Democracy! Which Brand, Stalin’s of Jefferson’s? (San Francisco: The Spanish Relief Committee of San Francisco, 1937), 11, Hoover Institution Library Pamphlet Collection, NX4331, Hoover Institution Library.

[4] H.L Mencken, “The Truth About Spain,” The Baltimore Sun, January 22, 1939, quoted in Francis X. Connolly, “You Fear About Franco? Consider Some of the Facts,” America 60, no. 27 (April 8, 1939), 629.

[5] “Spanish Aid to American Independence,” Spain 6, no. 7 (May 1941), 5-8, 23.

[6] Francis X. Talbot, “May Franco Win in the United States as He is Winning in Spain,” Spain 2, no. 7 (July 18, 1938), 18, 39.

[7] F. Theo Rogers, Spain: A Tragic Journey (New York: The Macauley Company, 1937), 203.

[8] For an overview of the patriotic symbols present at the Capitol siege, see for example Matthew Rosenberg and Ainara Tiefenthäler, “Decoding the Far-Right Symbols at the Capitol Riot,” New York Times January 13, 2021 https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/13/video/extremist-signs-symbols-capitol-riot.html?smid=em-share. Accessed 18 January 2021.

Feature Image: