By Jorge Puma

The men always made themselves

from the material world

from rich villas

or the slums

“El Mayor” by Silvio Rodríguez

The triumph of Mao Zedong and the People’s Republic of China’s proclamation in 1949 caused a frenzy among the American anti-Communist establishment. A wave of persecution destroyed lives and reputations throughout American society. South of the border, Mexico’s revolutionary period (1910-1938) was a recent memory, and Mexican leftists experienced the last breath of the popular front spirit.

Adolfo Orive de Alba (1907-2000) was the son of a revolutionary army officer. He studied at the National High School no. 1 in the old San Ildefonso college building at Mexico City under Lombardo Toledano, the leading Marxist intellectual of the period. He graduated from the National Engineering School and got a scholarship from the Mexican government to study irrigation in the United States at the Bureau of Reclamation, an U.S. government agency. There, Orive de Alba learnt the practical skills necessary to break the dependence of the Mexican National Irrigation Commission to American experts.

Through Lombardo, Orive became close to President Lazaro Cárdenas. A left-wing sympathizer, Orive was part of a ring of Soviet spies in the 1930s and was involved in the financial scheme behind the smuggling of nuclear secrets from the United States.[1] Despite this hidden trajectory, Orive de Alba was part of Miguel Aleman’s cabinet as water resources minister and traveled to the United States in the 1950s to study the Tennessee Valley Authority.

The son of the marriage of minister Orive with a Texan woman, Adolfo Orive Bellinger, was born in 1940 at Tijuana and lived his early years at the Lomas de Chapultepec, one of the wealthiest neighborhoods of Mexico City. Growing up a problematic teenager, his father decided to send him to a military academy in the United States. A thirteen-year-old Orive Bellinger traveled by plane to Chicago and then by train to South Bend, Indiana. His destination was half an hour by car, the Culver Military Academy.

A small elite school next to a gorgeous lake in northern Indiana, Culver was the refuge of the rising Mexican bourgeoisie that sent their children to learn English and discipline. A men’s only institution until the 1960s, Culver provided “an education for responsibility.” Swimming, polo, and gun practice alternated with lectures on literature, mathematics, and chemistry. A little blond kid, Orive Bellinger, was praised for his academic progress as he obtained the highest grades of his cohort in 1953 and the next year for the whole school.[2] Years later, he remembered his experience in Culver fondly and expressed that his contact with the United States reinforced his will to become a revolutionary.

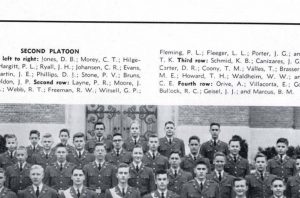

Adolfo Orive Bellinger as a cadet in Culver (Left to right, first of the fourth row), “Roll Call 1954”, photo by Culver Military Academy

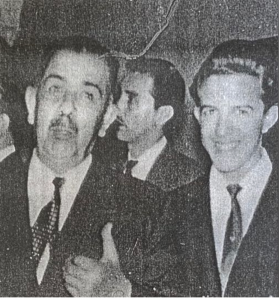

After returning to Mexico, Orive Bellinger became president of the students’ society of the National High School no. 1 in 1957 during rising political mobilization. During this period, Orive sided with the teachers and rail workers to fight for their unions’ independence while students marched on the streets in their support and demanded that the government lowered the price of bus tickets.[3] The rise of union insurgency and student militancy provided the local impetus to the formation of a broad left-wing coalition inspired by the Cuban revolution of 1959 and the decolonization process in Africa and Asia. Then, in August 1961, old family friend Lázaro Cárdenas called for the formation of a National Liberation Movement (MLN) to defend the Cuban Revolution. Hearing Cardenas’ call to aid Cuba, Orive traveled to the island in 1961 during the Bay of Pigs crisis.[4]

Adolfo Orive Bellinger (right), as president of the students’ society of the National High School, and Lázaro Cárdenas (left) after the general returned from a trip to the Soviet Union and China, ca. February 1959, Personal archive of Adolfo Orive, with the permission of Adolfo Orive.

Orive graduated as a civil engineer at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) in 1963. Nonetheless, he wanted to learn about Marxism and Revolution. Using a scholarship from the UNAM, Orive Bellinger traveled to Paris in 1963 and got access to the graduate seminars that the economist Charles Bettelheim conducted in the École Pratique des Hautes Études.[5] At that time, Bettelheim was one of the major players in the intellectual discussions on implementing socialist economic plans outside the Soviet camp. Third World governments (India, Egypt, Cuba) sought his help in development planning.[6] During the late 1960s, his intellectual prestige and connections helped Maoism spread into a small but influential group of French and international students.

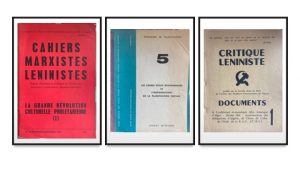

Meanwhile, Orive filled his shelves with Marx, Engels, Lenin, and Stalin works in French. He read Althusser, Balibar, Samir Amin, Bettelheim, and French translations of soviet authors to understand planning, transition problems to Socialism, and Imperialism. During this period, Orive read the original discussions on the Chinese Cultural Revolution published by the Communist student organizations in Paris and he participated through in-class discussions when Althusser and Bettelheim’s students led joint seminars. Orive Bellinger shared the classroom with Robert Linhart, the leader and founder of the UEC (ML), the direct antecedent of the Gauche Proletarianne of the post-1968 period, and Marta Harnecker, the foremost popularizer of Althusser’s thought in Latin America.[7] This intellectual and political experience left a deep mark on the young Orive.

Adolfo Orive Bellinger’s Maoist readings at Paris, Mexico City, 2020, Adolfo Orive Bellinger’s personal library, photo by Jorge Puma.

After four years in France, Orive Bellinger decided that he needed a more orthodox economic education and moved to Cambridge to work under Joan Robinson, a famous left-wing Keynesian economist. He spent one year in England while political turmoil turned many former French classmates into union activists. In the meantime, he deepened his admiration of Mao’s ideas of participatory democracy and prepared himself to return to Mexico just in time to participate in the 1968 student movement. Orive’s acquaintance with Robinson coincided with Robinson’s more Maoist period when she was part of the Cultural Revolution policies’ intellectual admirers. [8] Her support of China’s anti-imperial example motivated dozens of South Asians and Latin Americans to join Maoist inspired organizations.

Orive came back to Mexico on June 17, 1968. Filled with provocative ideas on achieving social transformation, he became the founder of a small but significant group of young activists determined to “serve the people” and change Mexico.

Adolfo Orive Bellinger’s participation in peasant mobilization at Peñita de Jaltemba, Nayarit, Newspaper El Nayar, September 6, Mexico, 1971.

Author’s Bio: Jorge Puma is a PhD in History candidate by the University of Notre Dame and a doctoral student in the Université Paris-Saclay. Jorge is a Kellogg Institute PhD Fellow and a Fulbright-García Robles 2017 alumnus. Jorge’s research focuses on a transnational community of revolutionaries and student radicals that adopted French Maoism and their interaction with Catholic activism inspired by the Second Vatican Council. Twitter: @JorgePuma4

Further Reading

Alexander, Robert J. International Maoism in the Developing World. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers, 1999.

Belden-Fields, Arthur. Trotskyism and Maoism. Theory and Practice in France and the United States. New York: Autonomedia, 1988.

Cook, Alexander C. Mao’s Little Red Book: A Global History. Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Kelley, Robin D. G., and Betsy Esch. “Black Like Mao. Red China and Black Revolution.” Souls 4 (Fall 1999): 14-21

Puma Crespo, Jorge Ivan. “Small Groups Don’t Win Revolutions. Armed Struggle in the Memory of Maoist Militants of Política Popular.” Latin American Perspectives 44, no. 6 (November 2017): 140-55.

Robcis, Camille. “”China in Our Heads” Althusser, Maoism, and Structuralism.” Social Text 30, no. 1 110 (2012): 51-69.

Soldatenko, Michael “The Various Lives of Mexican Maoism: Política Popular, a Mexican Social Maoist Praxis.” Chap. 9 in México Beyond 1968: Revolutionaries, Radicals, Repression During the Global Sixties and Subversive Seventies, edited by Jaime M Pensado and Enrique C. Ochoa, 175-94. Tucson, Arizona: University of Arizona Press, 2018.

Zolov, Eric. The Last Good Neighbor: Mexico in the Global Sixties. Duke University Press, 2020.

Endnotes

[1] For Adolfo Orive de Alba’s role as a soviet spy see John Earl Haynes, “Mexico City KGB ▬ Moscow Center Cables Cables Decrypted by the National Security Administration’s Venona Project,” ed. National Security Administration (Washington, D.C.: Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, 2011).

[2] For Orive Bellinger’s record on the Culver Military academy see William L. Cross, ed. The Culver Roll Call Yearbook from the 1953-1954 School Year. (Culver, IN: Culver Military Academy, 1954), 96-97.

[3] “Adolfo Orive Bellinger” 1957-1983. Archivo General de la Nación. Fondo Gobernación. Dirección Federal de Seguridad, Box 192.

[4] For Orive Bellinger’s trip to Cuba see César Gómez Chacón, “Lázaro Cárdenas quiso combatir en Girón,” Diario Granma. ÓRGANO OFICIAL DEL COMITÉ CENTRAL DEL PARTIDO COMUNISTA DE CUBA, no. 106 (2011), http://www.granma.cu/granmad/2011/04/16/interna/artic06.html.

[5] Details of the personal and political life of Adolfo Orive Bellinger are mainly from interviews conducted in the last eight years in Mexico City by the author: Adolfo Orive, interview by Jorge Puma, August 10, 2012 and Adolfo Orive Bellinger, interview by Jorge Puma, July 16, 2018.

[6] For Charles Bettelheim trajectory see Francois Denord and Xavier Zunigo, “Révolutionnairement Vôtre. Économie marxiste, militantisme intellectuel et expertise politique chez Charles Bettelheim,” Actes de la Recherche en Sciences Sociales 158 (2005).

[7] For Robert Linhart’s experience as a voluntary worker and Maoist activist see Virginie Linhart, Volontaires pour l’usine. Vies d’établis (1967-1977) (Paris, France: Le Seuil, 1994), 23-93.

[8] For Joan Robinson’s engagement with Maoist China see Pervez Tahir, Making Sense of Joan Robinson on China (Springer Nature, 2019).

Feature Image: For a Mass line, Línea Proletaria pamphlet, (1978), Jorge Puma’s personal archive, photo by Jorge Puma.