By Jessica Albrecht

When the so-called First Wave of feminism is remembered, as it has been in the previous years, it is usually thought of as a time of women’s enfranchisement in the “western” world.[1] As it is told, women and some men fought for women’s rights in terms of vote, divorce and education. These achievements then “swept” over to the non-western regions. The problem with that story is not only that it veils the global entanglements of women’s movements, which is another important story to tell, but also that there have been debates on the image, societal importance and meaning of women and womanhood apart from a mere equalisation with men. Namely, the female body as well as mothering role became important in what can be called eugenic feminism.

The period of the first wave of feminism can be described as something along the lines of what we now call feminism of difference. Women and men were conceived as something inherently different, a view which was maintained and constantly reaffirmed by two formative aspects of culture at the end of the nineteenth century: religion and nationhood.[2] The new colonial, global world enabled new, previously unimagined, travels of persons and ideas. These cultural encounters also resulted in the need to (re)-define one’s own religions and national identities. Scholarship on religious history agrees that it was this formative period which brought out what we now know as “world religions”. On the one hand, these religions had to define themselves in difference to each other. On the other hand, they had a common enemy against which they had to defend their authority: science.[3]

The nineteenth century also bears witness to the emergence of new religious movements, such as spiritualism and occultism. These movements wanted to reunite the differentiation of science and religion by combining both in their teachings. By the end of the century, a new actor stepped onto the global stage of religious history: The Theosophical Society (TS).[4] Many women joined the TS and many of them were feminists.[5] The society enabled women to be religious leaders and proclaimed that women and men are equally important parts in the cosmic evolution of humankind.[6] In this view, the gendered implications of colonial rule, which defined “the west” as masculine and rational and rendered “the east” as feminine and spiritual, which could be overcome.

The nineteenth century was also a time in which new “scientific” knowledge was produced on the issue of race and heredity. It was the beginning of eugenics. In Britain, the Eugenics Education Society (EES) was founded in 1907. Their primary aim was to develop ideas on how to enhance the possibilities for the procreation of the “fitter” ones – so called positive eugenics. This was highly connected to ideas of class as well.[7] However, eugenic ideas were often used to argue for women’s rights and improving their status in society.[8] Unsurprisingly then, there were overlaps between the eugenic movement and the TS. Two early members of the EES were Florence Farr (1860-1917) and Frances Swiney (1847-1922).

Florence Farr, playing in “A Sicilian Idyll”

They reversed the common discourse on “superman” and genius, which was often connected to men, and argued that the evolution of humankind would be introduced by the “superwoman”. This idea of the superwoman based itself on notions of womanhood that defined woman as mother and teacher of the forthcoming generation. However, the superwoman was compared to the goddesses Kali and Isis, as well as Amazons, something which is unthinkable without the influence of the TS and its adoptions of “non-western” religious ideas.

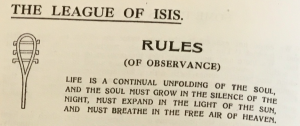

The League of Isis‘ Rules of Observance. 1910.

Frances Swiney even founded her own society in 1907, the League of Isis. With this she wanted to help the education of the youth as well as parents in good parenting and sexual conduct. Both Farr and Swiney maintained that only women, as the ones from whom life originates, should be allowed to choose their partner and be the ones to stop the degeneration of the race.[9]

Farr and Swiney are exemplary for the combination of newly developed feminist idols, such as goddesses, contemporary ideas on national and gender superiority as well as religion. As such, they regained agency within the discourses of religion, nationhood and sexuality that initiated the forthcoming changes in the course of the twentieth century and global rise of feminisms.

Author’s Bio: Jessica Albrecht is a PhD student at the University of Heidelberg (Germany). In her research she focusses on the entanglement of feminism, religion and esotericism in the British Empire and Sri Lanka, 1880-1920. Jessica has co-founded and is editor of the postgraduate journal and blog En-Gender! a working paper series on interdisciplinary gender research.

Further Reading

Angelique Richardson. 2003. Love and Eugenics in the Late Nineteenth Century. Rational Reproduction and the New Woman. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Joy Dixon. 2003. Divine Feminine. Theosophy and Feminism in England. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press.

Alex Owen. 2004. The Place of Enchantment. British Occultism and the Culture of the Modern. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Endotes

[1] This version of the history of feminism has been told in various museums, exhibitions and events celebrating 100 years of women’s suffrage.

[2] See: Bland, Lucy. 2001. Banishing the Beast. Feminism, Sex and Morality, London: Tauris.

[3] See for further discussion: Bergunder, Michael. 2016. ‘“Religion” and “Science” within a Global Religious History’, Aries 16, 86-141.

[4] Founded in 1875 in New York by Helena Petrovna Blavatsky and Henry Steel Olcott, it came to be the most influential new religious movement. Not only did they have an immense impact on various religions, such as Hinduism and Buddhism, in their search for the ‘Truth Religion’, but they also somehow eclectically combined “western” and “eastern” religious ideas and traditions and created esotericism in a form that is still relevant today. For example, many religious reform movements around the world were supported by the Theosophical Society in their attempt to denounce Christianity and revive their “older” religions. Important reformers in this regard were Swami Vivekananda, Anagarika Dharmapala and D. T. Suzuki. Many modern esoteric movements such as Wicca, goddess spiritualities, the New Age Movement, etc. are influenced by or drew on ideas of the Theosophical Society.

[5] The most prominent feminist member, Charlotte Despard even wrote a book called “Theosophy and the Women’s Movement” (1913) in which she argues that theosophy and feminism are inseparably linked.

[6] Blavatsky, H. P. 1888. The Secret Doctrine, London: Theosophical Publishing House.

[7] In Britain as well as many other countries, the view that the “race” was degenerating was quite dominant due to high maternal and child deaths and venereal diseases.

[8] For thorough research in this regard see: Richardson, Angelique. 2003. Love and Eugenics in the Late Nineteenth Century. Rational Reproduction and the New Woman. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[9] This race was either defined as national, such as British, or the human race in general, depending on the contexts in which they spoke.

Feature Image: https://pixabay.com/illustrations/superwoman-heroine-mother-woman-5709443/