By Aaron Peters

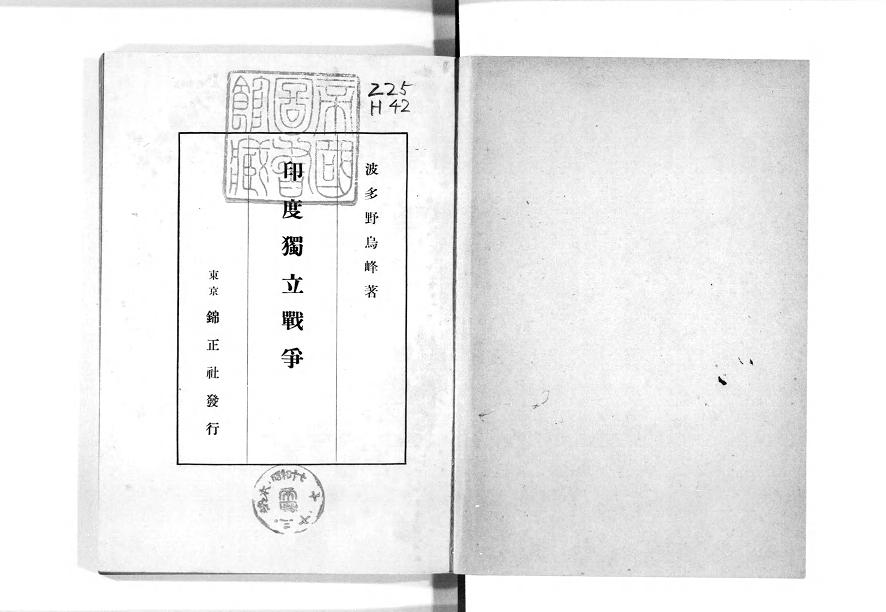

During the Asia-Pacific War (1937-1945) as Japan was extending its wartime empire across China and Southeast Asia to the borders of British India, a Japanese-language history of the Indian Rebellion of 1857 was published in May 1942 under the title, “India’s Independence War” (Indo dokuritsu sensō, 印度独立戦争). Its author was a man by the name of Hatano Uho. At the turn of the twentieth century, Hatano made a name for himself as a Pan-Asianist activist advocating for greater solidarity among the oppressed peoples of Asia and for Japan to support resistance movements against Euro-American colonialism. His account of the Indian Rebellion of 1857 is significant for two reasons. On the one hand, it is illustrative of Japan’s engagement with the world beyond the traditional reference points of East Asia, Europe, and the United States. At the same time, it is also reflective of the imperial ambitions that underpinned Japanese visions of a Pan-Asian internationalist order that aimed to restore the political independence and cultural authenticity of Asia. For men like Hatano, the history of Asia was one in which all roads ultimately led to Japan.

Not much is known about Hatano’s early life.[1] What is certain however is that at some point he became associated with Indian and Egyptian Pan-Islamist leaders in Tokyo, such as Abdul Hafiz Mohamed Barakatullah and Ahmed Fadli. Barakatullah and Fadli were among the numerous revolutionaries who gathered in Tokyo from all over the colonized world during the late 19th and into the 20th century. For anti-colonial nationalists throughout Asia and elsewhere fighting for self-determination, Japan’s victory over Russia in 1905 during the Russo-Japanese War shattered the myth of Western superiority and offered an attractive model of modernization without compromising the “authentic” spiritual traditions of the nation. Students, intellectuals, and revolutionaries flocked to Tokyo and other urban centers in Japan to learn the secrets of Japanese success as well as seek allies for their anti-colonial struggles at home.[2] Many found support from powerful Pan-Asianist organizations such as Gen’yōsha (Dark Ocean Society) and the Kokuryūkai (Black Dragon Society), who believed that it was Japan’s mission to assume a leadership role over Asia and guide its independence movements.

Through the journal that Barakatullah and Fadli ran titled Islamic Fraternity, Hatano became immersed in promoting greater awareness in Japan of issues facing the Muslim world and Asia generally under colonial rule. One of his pamphlets, titled “Asia in Danger” in which he called for greater solidarity between Asia and the Muslim world against the West, was translated into Ottoman Turkish by the Tatar journalist Abdürreşid İbrahim and published in Istanbul. In 1911, Hatano also became one the earliest Japanese converts to Islam, adopting the name Hasan.[3] However, Hatano’s relationship with Barakatullah soured when he reported him to the British consular authorities for unknown reasons. Bound by the Anglo-Japanese Alliance, the Japanese police were pressured to crackdown on anti-British revolutionaries and publications coming from Tokyo.[4]

By 1942, Hatano had abandoned his activism and was living a quiet life in a remote village nestled in the snowy mountains of Nagano. According to his preface, he was inspired to write his history of the Indian Rebellion of 1857 after Prime Minister Hideki Tojo declared the formation of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere and asserted Japan’s commitment to realizing an “India for Indians.”[5] Since the termination of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance in 1923, Japan’s policymakers and military leaders pursued imperial expansion by appealing to the language of Asian nationalism and supporting its independence movements. The Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere signified for its architects an alternate international order for Asia that rejected both the liberal internationalism of the League of Nations dominated by Britain and the United States, as well as the communist internationalism of Soviet Union. In practice however, the Co-Prosperity Sphere was an empire of client-states; nominally independent states whose resources, labour, and aspirations for self-determination were subject to the wartime needs of Japan.

Hatano’s account of the Indian Rebellion of 1857 follows a conventional narration of events. Yet it is apparent that he was aware of Vinayak Damodar Savarkar’s seminal nationalist account of the uprising published in 1909 titled, “The Indian War of Independence of 1857”. Savarkar claimed that the rebels of 1857 were primarily motivated by a desire to protect both swadharma (religion) and swaraj (self-rule). For Savarkar, India’s national identity and political sovereignty were inseparable from the maintenance of its “authentic” spiritual traditions rooted in Hinduism.[6] As a leading Hindu nationalist, Savarkar presupposed that there existed a timeless Hindu nation that survived Muslim rule and would eventually overcome British colonialism. Savarkar’s views on the Hindu nation excluded India’s minorities such as Muslims and Christians, who were deemed foreign elements to be assimilated or expelled. However, his views were also anachronistic. As scholars have noted, it would be incorrect to assume that an overarching ideology determined the actions and goals the rebellion.[7] The rebels of 1857 were not thinking in terms of the Indian nation, let alone a Hindu one, and had more localized political and economic concerns in their resistance against the British East India Company.

Nevertheless, Hatano adopted Savarkar’s idea of swadharma and swaraj as being the overarching ideology that guided the aspirations of the rebels. However, he included an important twist. In his concluding chapter, Hatano explicitly connected the Indian Rebellion of 1857 with the Asia-Pacific War. For Hatano, this was a golden opportunity for Indians to wage a second war of independence against Britain. With the support of Japan, Hatano claimed that the Indian nation would be able to realize swadharma and swaraj within the framework of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, bringing India to its natural and authentic form (Indo honzen no sugata no kakuritsu, 印度本然の姿の確立).[8] Hatano ends his account by calling upon all Indians to take hold of the opportunity that Japan has presented to them and emulate the examples of the rebels of 1857 in sacrificing themselves for the sake of Indian independence.[9] When Hatano published his book, the Japanese military was already recruiting volunteers from captured Indian prisoners-of-war for the Indian National Army with the intention of liberating India from British rule with Japanese support. This army would later be famously reorganized and led by Subhas Chandra Bose from July 1943 until his death in August 1945.[10]

It is curious however that when translating swaraj, Hatano opts for “independence” (dokuritsu, 独立) rather than the more literal translation of “self-rule” (jichi, 自治). Swaraj in the sense of “self-rule” implied, among other things, Mahatma Gandhi’s own vision of an India that emphasized sovereignty of the individual over the state and rejected all forms of imperialism, whether British or Japanese.[11] But as nationalist leaders who were allured by the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity ideal would realize, “independence” in Japan’s empire of client-states meant independence from Euro-American imperialism but not necessarily from Japanese imperialism. Hatano’s account is revealing of the ways in which Japanese Pan-Asianist commentators promoted an ideal of Japan as the champion of Asia that would restore the region’s political sovereignty and cultural authenticity. However, this was ultimately an imperial vision that foreclosed the possibility of Indians as capable of achieving self-determination on their own terms. For Hatano, India’s first war of independence was merely a stepping stone towards the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, within which India would realize independence in the fullest sense under the guidance of Japan.

Author’s Bio: Aaron Peters is a PhD Candidate at the University of Toronto, Department of History researching 20th century Japan-South Asia relations. His dissertation is tentatively titled, “A Complicated Alliance: Indo-Japanese Relations, 1915-1952” and uses the Japan-South Asia case to understand the complicities between empire, nationalism, and internationalism.

Further Reading

Aydin, Cemil. The Politics of Anti-Westernism in Asia: Visions of World Order in Pan-Islamic and Pan-Asian Thought. New York: Columbia University Press, 2007.

Duara, Prasenjit. Sovereignty and Authenticity: Manchukuo and the East Asian Modern. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2003.

Ramnath, Maia. Haj to Utopia: How the Ghadar Movement Charted Global Radicalism and Attempted to Overthrow the British Empire. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2011.

Saalar, Sven and Christopher W. A. Szpilman, “Pan Asianism as an Ideal of Asian Identity and Solidarity, 1850-Present” in The Asia Pacific Journal: Japan Focus Vol. 9, Issue 17, No. 1 (April 25, 2011).

https://apjjf.org/2011/9/17/Christopher-W.-A.-Szpilman/3519/article.html

Tanaka, Stephen. Japan’s Orient: Rendering Pasts into History. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1993.

Yellen, Jeremy. The Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere: When Total Empire Met Total War. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2019.

Endnotes

[1] Hatano Uho is sometimes confused with Hatano Yosaku (1884-1936), a Japanese intelligence agent who was engaged in espionage in Xinjiang during the Russo-Japanese War. However, from the preface and publication date of Indo dokuritsu sensō, it appears that Hatano Uho and Hatano Yosaku are indeed two different people. See Noda Jin, “Japanese Spies in Inner Asia during the Early Twentieth Century” in The Silk Road, vol. 16 (2018): 21-29, ElMostafa Rezrazi, “Pan-Asianism and Japanese Islam: Hatano Uho: from Espionage to Pan-Islamist Activity” in Annals of Japan Association for Middle East Studies vol 12, (1997): 89-112.

[2] Cemil Aydin, The Politics of Anti-Westernism in Asia: Visions of World Order in Pan-Islamic and Pan-Asian Thought (New York: Columbia University Press, 2007).

[3] Aydin: 85. See also Renée Worringer, “Hatano Uho: ‘Asia in Danger,’ 1912,” in Pan-Asianism: A Documentary History Vol. I 1850-1920, edited by Sven Saalar and Christopher W.A. Szpilman (Rowman & Littlefield, 2011): 149-160.

[4] Maia Ramnath, Haj to Utopia: How the Ghadar Movement Charted Global Radicalism and Attempted to Overthrow the British Empire (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2011): 223-225.

[5] Hatano Uho, Indo dokuritsu sensō (Kinseisha, 1942): 1-9.

[6] Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, The Indian War of Independence of 1857 (London, 1909): 7-10.

[7] Gautam Bhadra, ‘Four Rebels of 1857’, in Subaltern Studies IV, edited by Ranajit Guha and Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak (Delhi: OUP, 1988): 130-145.

[8] Hatano, 364-365.

[9] Hatano, 372-373.

[10] Joyce Lebra, The Indian National Army and Japan (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2008).

[11] For Gandhi’s critique of Japanese imperialism see Mahadev Desai ed. “A Japanese Visitor” in Harijan Vol. 6, No. 46 (Poona: December 24, 1938): 404.

Featured Image: Title page of Indo dokuritsu sensō. 1942. National Diet Library Digital Collection, Tokyo, Japan. Accessed March 14, 2021. https://dl.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/1042555