By Adrian J. Browne

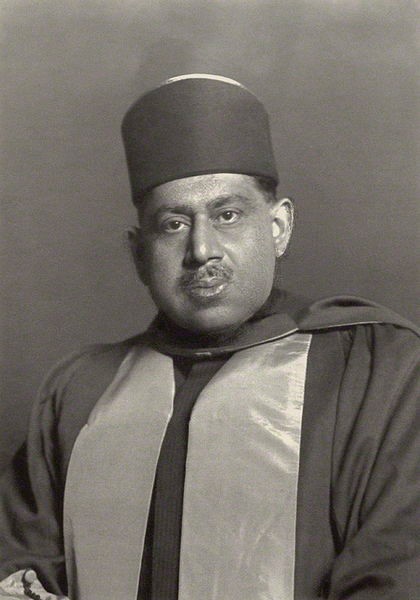

In the world of party schools for political education in inter-war Britain, one of the most dedicated participants was a middle-aged Indian intellectual advancing a very particular agenda. The political pedagogue in question was one of Bengal’s wealthiest land magnates, Sir Bijay Chand Mahtab, the Maharajadhiraja Bahadur of Burdwan. He was well known in London by the late 1920s as not only a ‘celebrated party giver, racehorse owner and dipsomaniac’ but also the self-styled ‘chorus girl of the British empire’.[1] The frequent lectures Mahtab enthusiastically delivered at the Conservative Party’s political schools in country houses were paeans to British imperialism. But these appearances were also exercises in persuasion, efforts to convince influential party members to support certain policies for India. Institutions of political education were essential tools in his bid to ‘safeguard vested interests’.[2]

Figure 1: Sir Bijay Chand Mahtab, Maharajadhiraja Bahadur of Burdwan, in 1931. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sir_Bijay_Chand_Mahtab,_Maharaja_Bahadur_of_Burdwan,_in_1931.jpg

Political education as an organised, ritualised form has a complex genealogy. But by the late nineteenth century in Europe and the US it was an increasingly left-wing domain. Its most important innovation was the party school, perhaps the best known of which was a Marxist-dominated initiative, founded in Berlin in 1906 by Germany’s Social Democratic Party.[3] The domestication of this form by parties and trade unions in different countries produced several variants on both sides of the Atlantic.[4] One of its instantiations in pre-war Britain was, from 1907, the summer school run by the Fabian Society, the gradualists affiliated to the Labour Party. After the war, party schools appeared in other locations – including Moscow, Tashkent, Vienna, Paris, and Chicago – spurred by the Bolshevik revolution of 1917, growing labour unrest, and, in some cases, expanding electorates.

Britain was for a time alone, however, in seeing a right-wing party, the Conservatives, developing institutions of political education with equal or greater urgency than the left. Annual summer schools inaugurated by the Conservatives in Scotland in 1920 soon led to a more substantial investment. Thanks to one donor’s largesse, the Tories from 1923 had at its disposal the UK’s one and only semi-permanent party school, the Philip Stott College of Social and Political Study, at Overstone Hall in Northamptonshire. Attended by thousands of party members over the next six years, the College sought to defeat socialism in the workplace, shore up support for British imperialism, and advance working-class Toryism.[5]

These practices had already begun to permeate across other sorts of boundaries in Britain. Indian participation in political schools can perhaps be traced back as far as 1914 when nationalist Lala Lajpat Rai attended the Fabian Society’s Summer School. But it was in the 1920s that party schools, particularly those of the Independent Labour Party and the Liberals, became spaces of intense struggle for Indian nationalists debating constitutional reform. One Conservative interloper at the Liberal summer school in 1930 derided ‘the very definite group of high caste Brahmins who, on the true [Indian National] Congress model, ran the whole School, spoke for it and told it what to do’.[6]

The Conservatives were amenable, however, to the sorts of Indians who used political education to less radical ends. One such man was Mahtab, who had long actively advanced his class interests in India, largely through landlord pressure groups. In 1927, he took a more active approach, beginning a protracted sojourn in the UK at the heart of Tory high society, mediating energetically between particular party factions and the Indian princely states. Mahtab and his allies saw structures of political education as an integral means by which to articulate and advance their shared goals for India. This engagement began when he attended the two-week Tory party school at the Stott College in 1928 to prepare himself to run for parliament – to become the ‘perfect antithesis of the fiery Communist, Mr [Shapurji] Saklatvala’, as one supportive commentator put it, referring to the only Indian MP.[7]

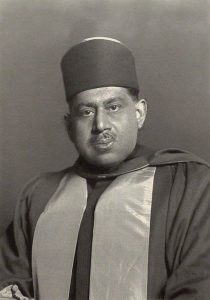

Figure 2: Ashridge Park, site of the Bonar Law Memorial College. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gardens_Old_and_New_Vol_1_Ashridge_Park_0121.jpg

Although Mahtab ultimately did not stand for election the following year, he did appear in the line-up of lecturers at the Tories’ new, expanded educational base, the Bonar Law Memorial College, housed in a Gothic mansion at Ashridge Park in Hertfordshire.[8] Mahtab was to be a fixture on this College’s programme over the next five years, using this platform to shape and advocate for a policy of provincial autonomy, as proposed by the National Government’s Conservative Secretary of State for India.[9] With Mahtab’s pedagogical assistance, the Government of India Bill in 1935 overcame considerable opposition from both backbench Tory diehards like Winston Churchill, for whom it was too radical, and Indian nationalists, for whom it was too conservative. With his mission all but complete, he returned to India at the start of 1935, the year the Act passed into law.

Mahtab’s time in London represent the beginning of what was to be a lengthy engagement between colonial émigrés and the political education agencies of all the main parties. Mediating the relationship between the colonial subjects and metropolitan parties, these institutions from the outset represented prime sites of paternalist colonial tutelage, but also, to use Priyamvada Gopal’s phrase, ‘reverse tutelage’.[10] Mahtab’s story demonstrates, however, that the lessons imparted by these means were sometimes far from radical. These tools were to be wielded increasingly competitively by a variety of actors, to diverse ends and effects, as the Cold War emerged and interacted with the decolonisation of Asia and Africa.

Author’s Bio: Adrian J. Browne completed a PhD in History at Durham University in 2020. His thesis explores ethnicity, class, and colonial violence in Uganda’s Northern Albertine Rift Valley. His current research focuses on political education, decolonisation, and the Cold War.

Endnotes

[1] Omkar Goswami, ‘Sahibs, Babus, and Banias: Changes in Industrial Control in Eastern India, 1918-50’, The Journal of Asian Studies 48, no. 2 (1989), pp. 289-309; ‘Notes of the day’, The Bombay Chronicle, 27 February 1928.

[2] ‘Interest in India’, The Times of India, 12 March 1931.

[3] Nicholas Jacobs, ‘The German Social Democratic Party School in Berlin, 1906-1914’ History Workshop (1978), pp. 179-187.

[4] Ralph Carter Elwood, ‘Lenin and the Social Democratic Schools for Underground Party Workers, 1909-11’, Political Science Quarterly 81, no. 3 (1966), pp. 370-391.

[5] Stuart Ball, Portrait of a Party: The Conservative Party in Britain 1918-1945 (Oxford, 2013), pp. 294-296.

[6] Bob Transit, ‘Uplift in arcady’, The Graphic, 23 August 1930.

[7] ‘Maharaja as M.P.?’, Derby Daily Telegraph, 15 June 1928.

[8] For more on this particular college, see Clarisse Berthezène, Training Minds for the War of Ideas: Ashridge College, the Conservative Party and the Cultural Politics of Britain, 1929-54 (Manchester, 2015).

[9] For some of his lectures from a US tour, see Bijay Chand Mahtab, The Indian horizon (London, 1932).

[10] Priyamvada Gopal, Insurgent Empire: Anticolonial Resistance and British Dissent (London, 2019).