By Thomas Wright (tw546@york.ac.uk)

During the fight for control of Central Kenya in the early years of the Mau Mau Emergency, authorities used collective punishments as the primary method to impose their dominance over the recalcitrant Kenyan countryside. Yet, in recent years, influenced as much by events in the media and court room as elsewhere, the field of Mau Mau studies has overlooked such forms of more wide-ranging coercion for a fixation with notions of interpersonal violence.[1] This article will use a collective punishment case in the village of Kanyoni to demonstrate the need to consider the wider range of coercion at play during the Mau Mau Uprising beyond violence.

On 22nd November 1952, amongst the commotion of Kayoni’s early afternoon market, a different kind of meeting was taking place. Between the stalls and the passing trade, an illegal oathing ceremony, binding the people of the little Kiambu village, willing or otherwise, to the cause of the militant secretive society of Mau Mau. A boxy but bustling village neighbouring the Kenyatta family home at Ichaweri, Kanyoni was to be the site of an early example of the Kenya Administrations quotidian fight back – the collective punishment.

It was a full week before news of the illegal practice reached the District Officer, John Tennant. In spite of the footfall at the busy market and the inevitable passer-by, news of the crime was brought forward only by a young village girl who had been an unwilling participant in the banned practice. To break ones oath was thought to incur supernatural retribution but it also carried the very substantial danger of Mau Mau retaliation.[2] Dismayed at the intractability shown by the Itura,[3] Tennent wrote to the Chief Native Commissioner that it was now “essential that both “good” and bad alike should bear blame and punishment.”[4]

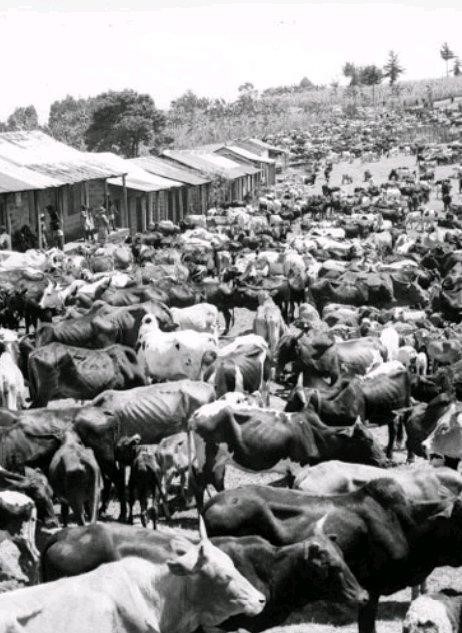

This solution was the collective punishment, a punitive measure designed to penalise a group, neighbourhood, or area for either the perceived failure to aid authorities in the prevention of crime, and/or the failure to bring forward assumed information which could lead to its perpetrators capture. The form of this punishment was diverse, from forfeiture of livestock, crops and property to monetary fines and even the cancellation of labour contracts. Accompanying repressive measures also included forced communal labour and the concentration and occupation of villages. Waiting on receipt of the Kanyoni case at the District Commissioner’s office in Kiambu, Anthony C.C. Swann, an experienced administrator and distinguished military man, wasted no time in giving his recommendation towards Tennent’s seizure of livestock and bicycles:

“I cannot think of a clearer instance where the local inhabitants must have had full knowledge of this breach of the law, and not only taken no action to prevent it, but took no action to report the matter to the authorities.”[5]

Kanyoni, as an illustration of a collective punishment, is emblematic of a process that would see itself repeated hundreds of times in the districts and provinces of Kenya throughout the Mau Mau rebellion, but as a case is a prosaic and clear-cut standard for how the punitive measure was intended to operate. Even in this banal example, the collective punishment demonstrates specific distortive and arbitrary qualities which would be replicated again and again throughout the emergency. The authority of action granted to the man-on-the-ground to act with impunity within his own district empowered the District Officials to react to a perceived challenge first and deal with the potential fallout of this later. Tennent’s decision to conduct a 50% forfeiture of livestock, itself an arbitrary number based not in regulation but in the administrator’s assessment of the seriousness of the case, was later reduced on investigation which showed some of the livestock seized belonged to known loyalists and therefore was to be returned.[6]

The closure of the market for two weeks not only had a significant impact on traders, but also in the sale of excess crops grown in the shambas of the Itura as part of the domestic economy. For those shopkeepers who had lost their bicycles, they no longer had access to their primary means of transportation and for the residents who had livestock seized, a significant proportion of their livelihood had been taken away. Against the background of the violence and dislocation of the Mau Mau emergency as a whole, the example of Kanyoni represents only a minor footnote in the British counter-insurgency campaign, but for the inhabitants of the small Kiambu village, the disruption and distortion was a complete upending of their everyday lives.

The case at Kanyoni presented here offers only a glimpse into the wider ranging coercion at play in Kenya. However, as accounts of violence and brutality are all too often relativised and explained away in Britain’s contentious imperial history wars, cases that turn attention to the prosaic and everyday can help to make the compelling case for the inherently sinister nature of colonialism all the clearer. While there can be little doubt that these arguments will continue to rage on, it is perhaps now time for historians of empire to turn their attention to the everyday rather than the exceptional as they persist to uncover the depths of coercion and injustice at play in Britain’s late colonial wars.

Author’s Bio:

Thomas Wright is currently a PhD Student at the University of York. His current project studies control in the Mau Mau Uprising in Kenya, with specific focus on the quotidian coercion beyond interpersonal violence.

[1] Cobain. “Foreign Office hoarding 1m historic files in secret archive.” The Guardian. 18th October 2013. https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2013/oct/18/foreign-office-historic-files-secret-archive

[2] Branch, Defeating Mau Mau, 52-54.

[3] Itura is a Kikuyu term for the local neighbourhood or community.

[4] Report from District Officer, Kiambu, in accordance with Regulation 4A, Section 2, of Emergency (Amendment) (No. 3) Regulations, 1952. 4th December 1952. The National Archives, London. [Hereafter TNA]. FCO 141/5933 (1/2)

[5] Seizure of Stock, DC Kiambu to PC CP, 4th December 1952. TNA, London. FCO 141/5933 (1/1)

[6] Member for Law and Order presenting his opinions for Y.E, 2nd January 1953. TNA, London. FCO 141/5933 (11)

Feature Image: Image://twitter.com/historykenya101/status/1392038080715046914