By James Halcrow

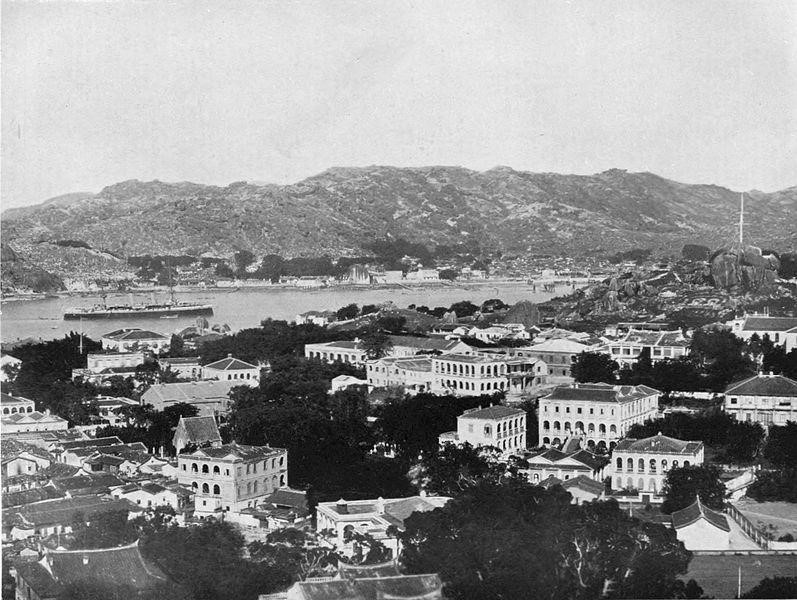

Kulangsu (Gulangyu) Island was host to Amoy’s (modern day Xiamen, in the Fujian Province, China) foreign resident community during the long nineteenth century. The port city had been forcibly opened to Western trading at the end of the First Opium War in 1842. By 1900, a population of around 280 foreign residents lived on Kulangsu Island.[2] On the shoreline opposite in Amoy city proper, the British Concession, established in the 1850s, stretched along the waterfront and included the warehouses and godowns (warehouses) of merchant corporations. The fairly routine lives of the Amoy business community, trading in tea, opium, and the transportation of coolies, were jarringly disrupted by the arrival of the Japanese military in 1900.[3] At the dawn of the twentieth century, Kulangsu became a hotly contested space. The foreign community on the island came together to find a local solution to international problems, and designated their living space as a concessionary space modelled on the Shanghai International Settlement.

Since the 1840s, Britain was the undisputed leader and principal beneficiary of the treaty port system. However, in the 1890s the British Foreign Office embarked on a policy of conscious disengagement in southern China. This policy fitted into what Thomas Otte describes as a wider geo-strategic ‘decision to re-orientate British policy in favour of Japan’.[4] My research aims to uncover the ways in which British statesmen viewed Japan as an important ally and a potentially useful pawn on the crowded chessboard of great power diplomacy in China, notwithstanding crudely racialised fears of ‘yellow peril’.[5] Such sentiment gained increasing currency in circles of power in the decade before the signing of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance in 1902. From the time Japan commenced its colonial rule of Formosa in 1895, British consular envoys and merchant communities presciently claimed that while it was ‘early in the day…the change of government [in Formosa] may possibly mean a transference of a portion of the trade from Amoy to Hongkong or Japan’.[6]

China’s shattering defeat in the 1894-95 Sino-Japanese War brought the pressures of international Great Game geopolitics in the Far East to the doorsteps of the grand Victorian manors, banks, and clubhouses of Kulangsu. The nexus of international power politics and localised concerns in treaty port China is deserving of further scholarship. The problems that residents of Amoy faced at the dawn of the new century is a useful crystallisation of the international becoming local. Japan wanted to be recognised as an equal player in the imperial club, and staked out its rights to exclusive concessionary and extraterritorial privilege in the Fujian Province ‘with the exception of the part already conceded to England’.[7] Coinciding with shifting dynamics in international power politics, China’s Qing Dynasty grappled with a volatile internal situation. The dynasty’s apparent inability to maintain order and the intervention of the foreign powers to suppress the Boxer Rebellion caused much unease among the foreign and indigenous residents of Amoy and Kulangsu Island.[8] These overlapping tensions and concerns helped contribute towards the sudden flashpoint of military occupation of one of China’s oldest treaty ports in the late summer of 1900.

On 26 August 1900, marine bluejackets dispatched from Japanese Formosa landed on the Kulangsu foreshore. The ostensible pretext for the Japanese landing party was the burning of a temple frequented by Japanese nationals in the British Concession. At best this was a flimsy excuse, and the British and American consuls found little evidence for concerted xenophobic attacks on Japanese nationals by pro-Boxer elements in the city.[9] In the wake of Japanese troops’ arrival, several thousand indigenous residents fled the city for the Fujian hinterland.[10] The civilian government in Tokyo, unimpressed with the army’s brazen manoeuvres, quickly recalled the troops. The Japanese Consul made apologetic overtures for thoroughly frightening the foreign and resident community, and committed to allowing normal business and trading activities to resume.[11]

The brief but memorable dramatics of the Japanese occupation of Amoy helped to pave the way for the creation of an International Settlement on Kulangsu Island—the one of only two in China, alongside the larger and better-known Shanghai International Settlement. Previous attempts in 1876 and 1897 to create a stronger form of municipal government for Kulangsu Island had failed because of Qing unwillingness to grant additional concessions.[12] Kulangsu was outside the boundaries of any formal concession and therefore feasibly open to the threat of opportunistic politicking or military action. Unlike in Kulangsu’s sister settlement in Shanghai, however, Britain abjured the opportunity to play the dominant role. A theoretical international settlement managed by a multinational municipal council would, it was hoped, ‘prevent any single Power, if she should fell [sic.] so disposed, to take possession of the Island’.[13] For a solution that would effectively neutralise the space, Japan would need to be included, and indeed, the Japanese Consul initiated the proceedings for the Settlement in 1901.[14] The Chinese government accepted the proposal in 1902, and in May 1903 the Kulangsu International Settlement came into existence.[15]

The residents of Amoy were increasingly concerned about the rise of great power tensions, and felt capable and influential enough to create a new international settlement and designate the island for themselves as a neutral concessionary space. Replete with a police force, municipal council and consular court dominated by a foreign elite, the new concession achieved a level of parity with the larger international settlement of Shanghai. The Kulangsu International Settlement came about as a local response to complex great power relations and showed how international crises could play out in a local way. The readiness of the consular community on Kulangsu Island to set aside grievances and the preparedness of the British to ‘make way’ in Amoy to the concert of treaty powers show that the links between local, regional and global were far from disparate or discrete.

Author’s Bio: James Halcrow is a doctoral candidate in History at the University of Auckland/Te Whare Wānanga o Tāmaki Makaurau. His research on the Chinese treaty ports reflect his broader research areas in nineteenth and early-twentieth century China’s relationship with the West, European concepts of Asia and Orientalism, and treaty port imperialism in China and Japan.

Suggested Further Reading:

Bickers, R. The Scramble for China: Foreign Devils in the Qing Empire, 1832-1914, London: Penguin, 2016.

Chen, Y. ‘The Making of a Bund in China: the British Concession in Xiamen (1852-1930)’, Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering, vol. 7, no. 1 2008, pp.31-38.

Chow, P. Britain’s Imperial Retreat from China, 1900-1931, Oxon and New York: Routledge, 2017.

Sibley, D. The Boxer Rebellion and the Great Game in China, New York: Hill and Wang, 2012.

Shirane, S. Imperial Gateway: Colonial Taiwan and Japan’s Expansion in South China and Southeast Asia, 1895-1945, Cornell: Cornell University Press, 2022 (forthcoming).

Endnotes

[2] ‘Amoy’, in Chronicle and Directory for China, Corea, Japan, the Philippines, Indo-China, Straits Settlements, Siam, Borneo, Malay States, &c. for the year 1894, Hong Kong: Hongkong Daily Press Office, 1894, p.177.

[3] Charles Drage, Taikoo, London: Constable Publishers, 1970, p.59.

[4] Thomas Otte, The China Question: Great Power Rivalry and British Isolation, 1894-1905, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007, p.63.

[5] Antony Best, ‘Race, Monarchy and the Anglo-Japanese Alliance, 1902-1922’, Social Science Japan Journal, vol. 9 no. 2, 2006, p.173; and Shih-tsung Wang, Lord Salisbury and Nationality in the East: Viewing Imperialism in its Proper Perspective, Oxon and New York: Routledge, 2019, p.189.

[6] ‘Service Report: 12 June 1895’, UK National Archives FO 228/1189: To and From Amoy and Hankow.

[7] ‘The Japanese Claims on China’, Japan Times, no. 638, 30 April 1899, p.2.

[8] Philip Wilson Pitcher, In and about Amoy: some historical and other facts connected with one of the first open ports in China, Shanghai: Methodist Publishing House China, 1912, p.32.

[9] ‘Telegram from Consul Mansfield: 26 August 1900′, UK National Archives FO 17/1430: Consuls at Amoy, Chefoo, Chinkiang, Chungking, Foochow, Hangchow; Mansfield, Hopkins, Tratman, Willis, Bennett, Fraser, Playfair, Clennell. Vice-Consuls at Pagoda Island, Shanghai; Werner, Hughes, Campbell. Diplomatic; and ’85. Landing Japanese Marines at Amoy. A. Burlingame Johnson to Hon. David S. Hill: 26 August 1900’, Despatches from U.S. Consuls in Amoy, China, 1844-1906.

[10] ‘Japanese at Amoy’, Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 03 September 1900, p.2.

[11] ’89. Withdrawal of Marines from Amoy. A. Burlingame Johnson to Hon. David S. Hill: 08 September 1900′, Despatches from U.S. Consuls in Amoy, China, 1844-1906.

[12] Robert Nield, China’s Foreign Places: The Foreign Presence in China in the Treaty Port Era, 1840-1943, Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2015, p.34.

[13] ‘August Piehl to F.M. Knoble, Esq. Minister Resident for the Netherlands: 22 March 1901’, Netherlands Nationaal Archief 2.05.90/71: Stukken betreffende de internationale nederzetting op het eiland Kulangsu te Amoy.

[14] ‘Meeting Held at the Japanese Consulate on the 20th March 1901′, in ibid.

[15] Nield, China’s Foreign Places, p.34.

Feature Image: Kulangsu Island in 1908, with the Amoy foreshore in the background: Arnold Wright (ed.), Twentieth Century Impressions of Hong-kong, Shanghai, and other Treaty Ports of China: their history, people, commerce, industries, and resources, London: Lloyd’s Greater Britain Publishing Company Ltd., 1908, p.815.