By Amanda Summers

The public may be most familiar with the Inquisition through Monty Python’s famous skit. “No one expects the Spanish Inquisition! Our chief weapon is surprise, fear, ruthless efficiency, an almost fanatical devotion to the Pope, nice red uniforms …”[1] The comedy troupe used humor to poke a little good natured fun at the institution and its place in popular memory. I want to use the imagery of their “questioning” and “torture” of the woman in the skit to bring you into how I think about the practices of the Inquisition in Spain and the colonies in the seventeenth century. The Inquisition was not so much a fan of surprise as of pomp public ceremonies called autos de fe, or “acts of faith”. Depending on the circumstances of the particular auto, these could be smaller, more private sentencings within the prisons or plazas of a town called an auto publico, or they could be grand multi-day festivals in urban power centers across the empire called an auto general. I’d like to introduce you to one of the latter, in fact the largest auto general ever held in Mexico City in the year 1649, and how we can use the events of the autos to learn more about the diverse people who inhabited and moved through the Spanish empire.

So What Happens in an Auto de Fe, and How Do We Know About It?

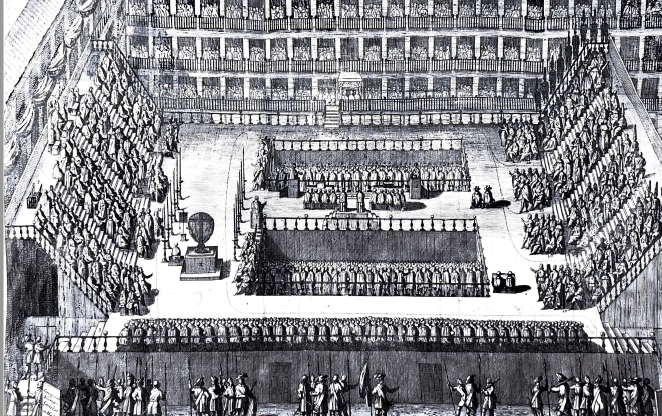

We as historians are very lucky indeed to have been left many rich documents with which to study the many facets of the Inquisition thanks to that “ruthless efficiency” Monty Python referenced. During arrests, trials, and imprisonments, Inquisition notaries kept detailed records on the experiences, quotes, concerns, and possessions of the accused, and the questions and concerns of the Inquisitors. Historians use these documents to take a deeper look into the lives of the accused, how they ended up before the Inquisition, and what their actions meant for the culture of the time. What we see in these documents are conflicts of religion of course, but also gender conflicts, interpersonal conflicts, and miseducations and resistance strategies of converted persons from the many cultures which came under imperial control. We also have some fantastic booklets that were produced during the autos, called relaciones. For larger festival-like autos, like the one in 1649, these relaciones contain great details of what people were in attendance and where they sat in the Plaza Mayor, the clothes worn by nobility, royalty, and Inquisitors, the sermons given, the street performances, and of course the reading of religious crimes and the sentences acted out upon the accused. Sometimes there are even stories told about notable figures appearing in the autos. Nobility and Inquisitors hired writers and artists to record the day for them, and every detail was captured. Some of the more valuable relaciones have gold foiled edges and beautiful artwork in them depicting the plazas and the autos.[2]

The relacion of the 1649 auto in Mexico City is a fantastically written example where we learn intimate details of over two-hundred people from three large kinship groups of converted Jewish persons, called conversos, who had been living in Mexico before coming before the Inquisition for various charges and punishments, including exile, labor, and death.[3] One converso woman in particular drew my attention, and I hope from her experience to open a door to new ways of thinking about the Inquisition, the records they left behind, how we as historians use them, and how the public can find and appreciate them.

Thinking About Doña Blanca Enriquez and Gendered Power

In Monty Python’s sketch, women are put to trial for heresy with a dish-drying rack and soft cushions. Of course this is a reverse of the experiences of women in the Inquisition prisons. So what did one woman’s experience look like?

Doña Blanca Enriquez was a Portuguese-descended converso woman from Seville, Spain who had the misfortune of being arrested by the Inquisition twice. One time in Seville and again in Mexico City. In the early seventeenth century, Portugal and Spain had been more unified under the Spanish crown in a period known as the “Iberian Union” from 1580-1640, but were divided again with the War of Portuguese Restoration against Spanish kings Phillip III and Philip IV.[4] These events led to an increased diaspora of conversos between Portugal, Spain, Mexico City and Lima, Peru.[5] Blanca’s family was among these diasporic conversos.

At the age of fifty, Blanca found herself in the secret cells of the Palace of the Inquisition. She spent seven years in the cells before her death. Before her arrest however, Blanca and her family had enjoyed a fair amount of comfort in Mexico, enjoying social and financial success with friendships and intermarriages among elites in the colony, even among the Inquisition. This all changed with events known as the “Great Plot” in 1642, where the Inquisition accused the Portuguese conversos of Mexico City of plotting to burn down their buildings.[6] This led to the widespread arrests and trials which made the massive auto of 1649 possible.

Blanca was presented as an important figure in the auto because of the prominent social role she held. She was advertised as a famosa Dogmatista y Rabbina[7], who taught Jewish religion and tradition among her family, arranged marriages, and led the community in clandestine practices. During the trials, many community members turned on Blanca to receive lighter sentences, and she was intended to take the brunt of punishment for them. This being her second time being arrested by the Inquisition, she was convicted of being a relapsed heretic with an irredeemable soul and sentenced to execution by garrotting and burning.

In this trial, Blanca was a paragon of women’s gendered power as it operated in resistance to imperial power. Inquisitors called her the “root and trunk of every Jew the public theater has seen in the four autos of this great, complicated trial… whose crimes the investigation has consumed so many years.”[8] This statement in her record, along with the extensive accusations against her, showed that she was seen as a keystone person in the tribunals stemming from the “Great Plot.” Blame for the ongoing practice of Judaism and rebellion against Catholicism, and in turn the Spanish Empire by her Portuguese converso community in this part of the empire was laid at her feet.

Blanca carried on a multi-generational tradition of cultural leadership. She is said to have inherited her mother’s disposition and inclinations for teaching Judaism and applied great care to teaching others. This tells us that this line of educational dedication and cultural preservation was believed to be handed down generationally among women. They claimed the reach of her “heretical taint” was so deep, it was evident that her mother had begun her education at the earliest age, a tradition that Blanca continued with the teaching of her extended family. From her gendered role as family and community educator and leader, and the language used in the relaciones, we can discern that Blanca occupied a privileged position of leadership, exercising an influence on par with the elite men she was tried alongside. This particular brand of power, that of women who passed belief and culture down through generations, was a remarkable concern to Inquisitors in this auto.

Thinking About Food, Culture, and the Body During Incarceration and Death

For many conversos trying to retain the practice of their faith and culture in secret, food and eating habits were one of the most likely factors in their denunciations, as it was the most easily observed deviation from Catholicism.[9] Food played a role for Blanca throughout denunciations, trial, and during her incarceration. She had been observed not eating at noon and not participating in certain Catholic rites and feasts. She had also been repeatedly observed following Jewish feasts and fasts, a fact she openly admitted to repeatedly in her trials.[10] But her fasting became of particular importance to her jailers as the auto approached.

Blanca had become gravely ill many times during her incarceration, often becoming bedridden. Her illness shortly before the auto was different. She gathered her kin close to her in the cells, and informed them she was close to death. They sent word to the Inquisitors that she had seen the omen of her death. She instructed the family on what to do with her body at the time of her passing. She ordered them to collect the teeth and hair which she had already lost and put them in the sepultura.[11] Her dying wishes, and the degree to which they were carried out, give us clues to Blanca’s deteriorated physical and emotional condition as she neared the end of her life.

Presuming Blanca died in her cell very shortly before the auto held on April 11, we can assume she had just observed Passover. During Passover, eating chametz is forbidden. Chametz is any food made from flour, wheat, barley, rye, oats, has come into contact with water, or been allowed to ferment or “rise”. Considering Blanca was being held in the cells of a Catholic institution, it is highly unlikely she and the others had access to the lamb, matzah, or bitter herbs that would be required as part of the holy remembrance, and as such the Inquisitors may have observed their actions as a fast. However it is highly unlikely that the following of this one fast would have led to her death, although this is what the Inquisitors attributed to her failing physical and mental condition in the last days of her life.

Following her last fast (presumably during the limitations available to her during Passover), after she congregated with her family and expressed her dying wishes, priests attempted to bring her the holy sacraments of extreme unction, despite her conviction as a relapsed and unrepentant heretic. Upon their arrival, she was said to display much evil and divine power. When they tried to administer the sacrament, her tongue grew large, fat, and blackened. She cried out her desire for death, that her tongue was filled with fire, and tried to tear it out of her mouth with her bare hands. In reaction, the priest attempted to apply a crucifixion to her tongue in an attempt to drive out the evil which was inflicting her. She looked at him in anger and bolted across her cell, clinging to the far wall. The priest reported that at this time she pledged her soul to the devil for perpetual condemnation for all the crimes and observances she had committed over the years and then she died.

There are several conditions which could have led to Blanca’s deteriorating condition on her final day of life. Her black, swollen tongue caught my interest in the relacion, as it was reported as having occurred immediately. What would cause a tongue to rapidly swell and blacken? The most obvious conditions would be allergic reactions. If there had been wine involved in the rituals, there is a possibility that Blanca had an allergic reaction to the nitrates in the wine. But we do not know for certain there was wine in the rituals. More likely, if she had an allergic reaction, it could have been to an insect or rat bite. Conditions in the secret cells in the 1640s were not sanitary, there would have been rats, spiders, scorpions, roaches, or other insects living among the inmates, along with, and perhaps thriving in, the human waste and filth in the cells. Even if Blanca had not come into the cells with an allergy, it is possible she could have developed reactions over time due to her living conditions and receiving repeated bites over time. Many types of reactions to bites begin with small reactions which increase in severity over time. If an allergic reaction to a bite occurred while she was in a weakened state from incarceration, starvation, and dehydration, this could be a potential cause for her tongue swelling and blackening, triggering the extreme reaction of the priest.

There are conditions stemming from long term unsanitary incarceration which would have affected Blanca and led to her death. She had asked her children to bury her teeth and hair, including those which had already fallen out which she had been saving in her cell, in the sepultura. Losing teeth and hair would have been normal from the lack of dental care at the time and poor diet she would have experienced during incarceration. It is likely Blanca would have had many dental caries, cavities which would cause her teeth to fall out. She could have had dental infections which could have led to sepsis, but this would not necessarily cause the sudden tongue swelling the way it was described. Starvation and dehydration have a number of physical effects, including abdomen distention and the drying out of mucous membranes, fevers, and headaches. They also cause discomfort from an inability to urinate, sweat, or swallow, the building up of uric acid in the body and joints, and eventual kidney failure causing poisoning of the body and a painful death. Blanca likely had chronic skin and urinary tract infections, and GI tract infections. Fasting would have contributed to the infections and ailments she was experiencing. If we consider the seven years she spent in unsanitary living conditions, and reported frequent fasts, there are a number of possibilities which could have come together on Blanca’s final day which contributed to her severe physical and emotional reaction, and in turn, the priests actions which ended her life.

Of course, it is more likely that there was no actual mystical element of the end of her life as was reported in the relaciones and that Blanca died as a result of the conditions she had been living in for seven years. To account for why such a kingpin of the tribunal had died just before the auto, Inquisitors would have had to come up with an explanation worthy of the event. A sudden revulsion to sacrament and death by possession or a surge in evil power would certainly provide cover for years of neglect and abuse when the tens of thousands of people were expecting to witness the execution of a famous rabbina.

Closing Food For Thought

In considering the stories told to explain the end of Blanca’s life, I think we have many ways to think about the religious and cultural elements that would have informed the story told to the public. So often in historical documents, an official record can be embellished with fantastical and mystical elements to explain events that didn’t go according to plan. Blanca’s story is no exception. Her experience as documented in the relaciones of the 1649 auto de fe give us a little more “food for thought” when we dig into her reported standing in the community, her cultural traditions and forced conversion, and the reasons given for her premature death to an anxious and elite public. In thinking about Blanca’s death, I conversed with current members of the medical community to discuss possible effects of long term incarceration, unsanitary conditions, starvation and dehydration on the aging woman’s body. I believe more collaboration between historians and medical practitioners can open new paths for how we think about the historical actor and how people experienced the events under study.

During life, Blanca inhabited a space of gendered power, where women were the cultural preservers who educated future generations, sometimes posing a threat to dominant religious and imperial powers. In incarceration and death, she experienced the converse of gendered power, as her treatment and death also took on a gendered element, one of a lack of power to maintain her health and privileged status.

Author’s Bio: Amanda Summers is a PhD student at Temple University in Philadelphia. Her dissertation in progress focuses on the diaspora of conversos in the Iberian Atlantic through the lens of the incarceration and death of women in Inquisition prisons in the seventeenth century, and puts histories of the Spanish and Portuguese empires into conversation.

Bibliography

Alberro, Solange. “Crypto-Jews and the Mexican Holy Office in the Seventeenth Century.” In

The Jews and the Expansion of Europe to the West, 1450-1800, edited by Paolo Bernardini and Norman Fiering, 1st ed., 172–85. Berghahn Books, 2001.

Bethencourt, Francisco. “The Auto Da Fé: Ritual and Imagery.” Journal of the Warburg and

Courtauld Institutes 55 (1992): 155–68.

Liebman, Seymour B. “The Jews of Colonial Mexico.” The Hispanic American Historical

Review 43, no. 1 (1963): 95–108.

Schwartz, Stuart B. 2008. All can be saved: religious tolerance and salvation in the Iberian

Atlantic world. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Studnicki-Gizbert, Daviken. 2007. A Nation upon the Ocean Sea Portugal’s Atlantic Diaspora and the Crisis of the Spanish Empire, 1492-1640. Oxford University Press.

Warshawsky, Matthew D. “Inquisitorial Prosecution of Tomás Treviño de Sobremonte, a

Crypto-Jew in Colonial Mexico.” Colonial Latin American Review 17, no. 1 (June 1, 2008): 101–23.

Wiznitzer, Arnold. “Crypto-Jews in Mexico during the Seventeenth Century.” American Jewish

Historical Quarterly 51, no. 4 (1962): 222–322.

Endnotes

[1] “The Spanish Inquisition”, Monty Python’s Flying Circus. Aired Sept 22, 1970.

[2] For example, “Inq-60,” 1680. BX 1735.o48 1680. Hesburgh Libraries, Notre Dame.

[3] Fragments of the relacion are available at Hesburgh Libraries, Notre Dame and Henry Charles Ley Library, University of Pennsylvania. The complete relacion is also available digitally via Miguel de Cervantes Virtual Library, 2010, Bocanegra, Matías de, 1612-1668, CDU 272.

[4] For deeper reading please see Daviken Studnicki-Gizbert’s A Nation upon the Ocean Sea: Portugal’s Atlantic Diaspora and the Crisis of the Spanish Empire, 1492-16-40, and Stuart Schwartz’s All Can be Saved: Religious Tolerance and Salvation in the Iberian Atlantic World.

[5] Alberro, Solange. “Crypto-Jews and the Mexican Holy Office in the Seventeenth Century.”

[6] Wiznitzer, Arnold. “Crypto-Jews in Mexico during the Seventeenth Century”

[7] HCL file Inq 52

[8] Biblioteca de la Universidad de Sevilla, Spain (BUS); accessible via Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/A0880401; Inquisición — México — Historia — Siglo 16

[9] See also Alberro, Allan, Giles, Jacobs, Kissane, Wiznitzer, Bodian, Warshawsky, Chuchiak, Greenleaf, Liebman, Taverner,Skinner, etc for further discussion on food and crypto-judaism.

[10] AGN Inq 61 vol 416 file 42, vol 413 file 54.

[11] Cervantes

Feature Image: INQ-60, Relacion from the Auto de Fe held in Madrid in 1680 dedicated to and attended by a young Charles II. Courtesy of Hesburgh Libraries, Special Collections, Notre Dame University.