Welcome to the Scottish Centre for Global History

The Scottish Centre for Global History (SCGH) is a research centre and public history space for postgraduates and academics from around the world to share their ideas and research in Global History.

Through our Research Seminars, Global History Blog and Podcast, our platform focuses on the development of global history; the democratisation of the field; and stimulating debate. Additionally, our Global History Resources provide researchers with a variety of resources to aid their research, such as our repository of online archives and databases.

We are flexible in how contributors would like to approach any potential project with us. For more information see our Write For Us and Podcast pages.

The University of Dundee

The centre brings together members of the School of Humanities and other academic schools at the University of Dundee with interests in Global History. Our work primarily ranges from the sixteenth to the twentieth century, and spans the globe. For more information see our About Us page.

Seminar Series 2022/23

Dr Laura Doak, from the University of Dundee, will be presenting a paper entitled The Privy Council and the People, c. 1692-1708.

Date: Wednesday, 7th December

Time: 4:30-6 p.m.

Venue: University of Dundee, Tower Building, Room T8

For further details, please see the Seminar Series page.

Tracing Global History through the BBC Monitoring Service

By Alex White The birth of international radio in the 1920s was marked by a feeling of utopian hope. A new type of media had emerged which could travel huge distances instantly, link distant peoples and build global communities through the human voice. International broadcasting, however, would soon be set on a different trajectory. Radio’s […]

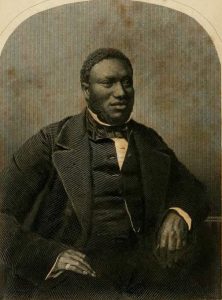

Samuel R. Ward and the Importance of Transatlantic Congregational Links to Reform Networks

By Kate Rivington Scholars have long recognised the importance of religious ties to the formation and maintenance of reform networks. Most notably, for transatlantic abolitionism, scholars have recognised the importance of long-standing Quaker connections, like those dating back to the late eighteenth century between the London-based Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade […]

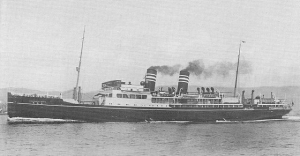

Children at Sea: Researching Juvenile Experiences on Trans-Pacific Steamships in the Early Twentieth Century

By Hayley Keon The clouds sat heavy over the harbour but they did little to dampen Louise van Evera’s mood. Writing in her diary on the 19th of November 1927, the twelve-year-old revelled in the day’s excitement, recording in detail the guests and gifts that her family had received as they prepared to depart Shanghai […]

At the Intimacy of the Home: Children’s Views of Private Life in Postrevolutionary Mexico

By Daniela Lechuga Herrero The Mexican revolution was a conflict that was experienced in different ways and with different intensities throughout the country. The postr-evolutionary governments, such as the one of Álvaro Obregón, Plutarco Elías Calles and Lázaro Cárdenas, strengthened their policies to recover the country’s stability. In addition to the improvements in education and […]

“A Penny From You” - Activism and Organisation in Edinburgh During the Spanish Civil War

By Harry Taylor The outbreak of Civil War in Spain in the summer of 1936 caused reactions across the globe. Whilst the leading powers in the world opted for a policy of containment designed to prevent another international conflict, countless men and women organised in support of the threatened Republican government. Most famously, this took […]

Food for thought: how Walter Millsap offered Toshiko Imamura intellectual nourishment during the deprivations of internment

By Henry Jacob It is always hard to miss the chance to offer a farewell in person. Leftist organizer Walter Millsap faced this scenario on May 12, 1942. That night, Millsap arrived at the home of his best friend Keikichi Imamura in Pasadena, California. Even after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Millsap remained close to […]

Women of the West End: the “Queen of the Night Clubs,” her Kingdom, and the Perceptions of Dance Hostesses in 1920s London

By Catherine Stainer In 1920s London, women were at the centre of the city’s nightlife. Kate Meyrick (1875-1933), dubbed the “Queen of the Nightclubs” by the press, was a pioneering businesswoman whose career as a nightclub proprietor spanned the length of the decade, despite five stints in prison for contravention of licensing laws.[1] In early […]

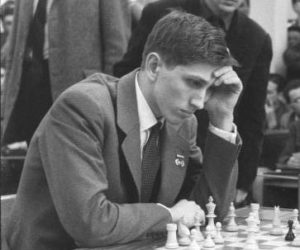

Chess and Cold War Diplomacy

By Prarthana Sen For decades, the Russians have been strong in chess as their leaders went about promoting the game ever since the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917. Chess became a favourite Soviet pastime, with tall political figures like Vladimir Lenin and Joseph Stalin being regular practitioners of the game. The strategic game could be seen […]

The Historian as Diplomat? John Erickson and the ‘Edinburgh Conversations’

By Niall Gray The historian’s relationship with government has always been a contentious subject. Called to inform and encourage debate across all sections of society, historians have repeatedly run into difficulties when engaging with state authorities. This is often due to the potentially sensitive topics that researchers wish to discuss, with the British government subsequently […]

An analysis of extreme weather events over the 1981 – 2018 period: A South African-based study

By Nomvula Mpungose Rainfall in subtropical southern Africa experiences substantial changes in space and time owing to factors such as regional orography, geographic position, impacts of large-scale climate modes (E.g. El Niño Southern Oscillation; hereafter ENSO), and changes in regional sea surface temperatures. The assessment of rainfall patterns and prediction of extreme rainfall events is […]

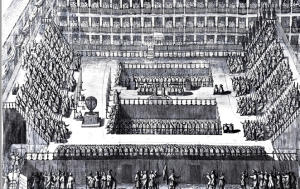

Rethinking the Spanish Inquisition and Autos de Fe

By Amanda Summers The public may be most familiar with the Inquisition through Monty Python’s famous skit. “No one expects the Spanish Inquisition! Our chief weapon is surprise, fear, ruthless efficiency, an almost fanatical devotion to the Pope, nice red uniforms …”[1] The comedy troupe used humor to poke a little good natured fun at […]

The Women’s War of 1929: Why Is It Still Relevant for Nigeria?

By Emma Davies In November and December 1929, tens of thousands of African women in South-Eastern Nigeria danced, sang, and marched in protest against an enforced and exploitative British colonial policy of taxation, and against patriarchal legal structures. These events have since been referred to as the Women’s War, the Aba Riots, or Ogu Umunwaanyi.[1] […]

[siteorigin_widget class=”SocialSnap_Social_Followers_Widget”][/siteorigin_widget]