By Rory Bannerman

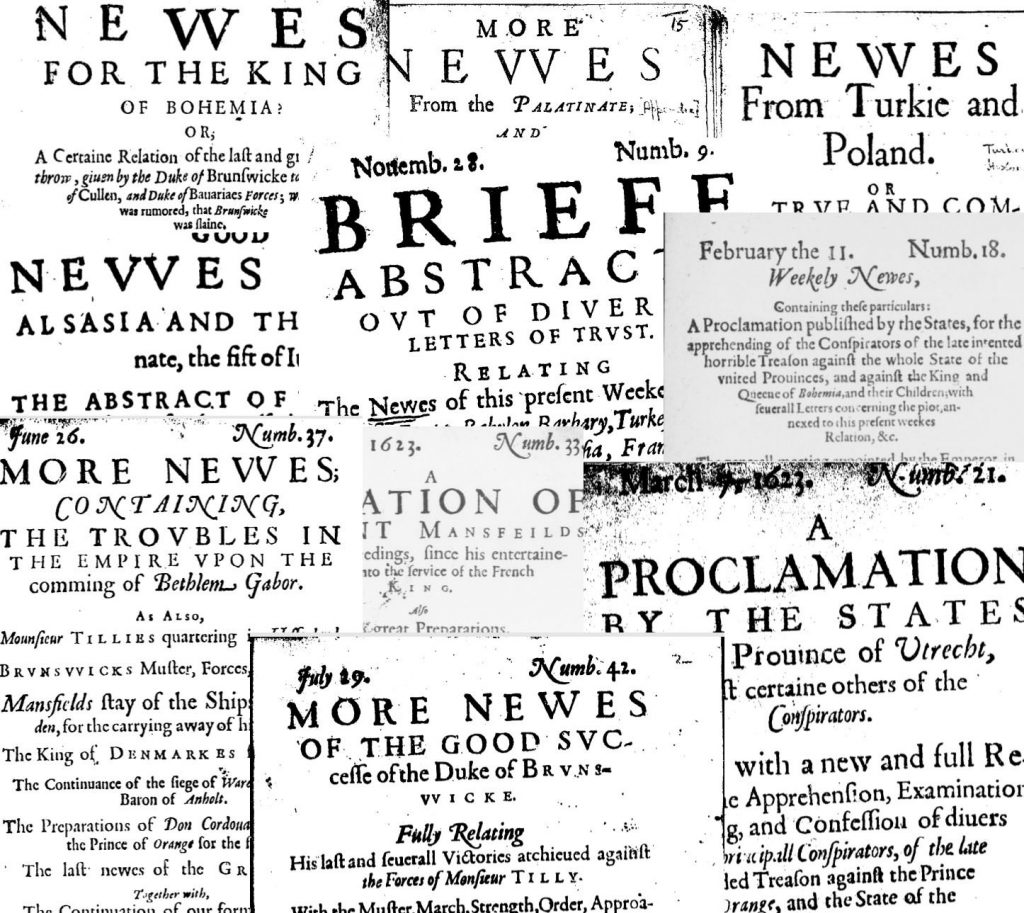

If you tear through an issue of The Economist or flick straight to the “World” or “Global” sections of your preferred broadsheet, you are taking part in a long tradition of consuming news of events beyond our borders. In Britain, the first publications devoted to relaying foreign affairs were published in London from 1618 onwards. The “news” was bought and sold as a commodity, passing through cross continental networks before stationers in the capital translated and compiled them into single publications for public sale. That they were compilations is especially easy to notice in the earliest publications, as different sections begin with titles such as “The News from Rome/Vienna/Prague.”

What was considered “news” to people of the early 17th century? and does it challenge our perceptions of what might be considered “newsworthy”? Taking samples of the earliest newsbooks from 1618 through to the death of King James in 1625, the content can be divided roughly into: warfare; military logistics; diplomatic missions; foreign court activity; natural disasters.

As one would expect, war takes up a large proportion of coverage, and as the publication of these newsbooks coincided with the outbreak of the Thirty Years’ War, there was a great amount of material available to publish. Details of the progress of sieges and which towns were being raided were regular features, e.g. “the Duke of Brunswicke..took diverse prisoners, ransack[ed] Patterborne, and Westphalia, marched as farre as Sipstate, sackt 8 or 9 townes”.[1] Yet, so were the more mundane details, such as where troops were raised, sums paid to soldiers, and even the logistics of assembling supply wagons, “This weeke sent againe sixtie Waggons with munitions, and amongst them five hundred bullets, which weighed 45 pound a piece.”[2] This content might seem less engrossing than battlefield heroics, but it does ground more exciting elements in plausibility and therefore helps establish trust with the readership, this being of the highest importance.

Accurate reporting was even more important to early news publishers than it is to current newspapers. In a similar way that new online media is treated with great scepticism, when printed news was the new medium, it had to establish itself as being worth people’s time; who would bother to read or purchase printed information that might be no better than the rumours and chatter heard around the city? Not only does this explain the dominant presence of less exciting reports, but also the practice of using sources from all sides of the conflict. This was done to the extent that sources from Catholics were included, despite the London readership being a majority Protestant one. However, usually some editorial spin would be mould these reports into a more suitable narrative, i.e. “The Spanish soldiers in Moravia doe tyrannize very much over the citizens and inhabitants” as opposed to the honourable behaviour of Protestant forces, “Mansfield…took enemy booty, left women unharmed”.[3]

News of other foreign courts are also a regular feature: e.g.“The Duke of Alderberg sent the priests and Jesuits out of the city”; “duke in Veeda, who was fined to pay 20000 Duckets to the King’s Exchequer, and banished 20 leagues from the Court”.[4] It has been suggested that such information would have been useful for merchants, bankers and civic delegations, (i.e. those who would be travelling to these locations and be interacting with such courts), especially on the occasions that local laws had been changed.[5] For example, “(From Naples) It is prohibited to weare any pistols or short Pistols or short Peeces…and there is likewise commanded, that much be made of all Strangers which shall arrive into that Kingdom.”[6]

With all of this, it is worth asking if more sensational stories still had value for the early modern readership. Certainly, stories of shipwrecks and lives lost in plagues, storms and other disasters are still reported on, but judging by how little space is devoted to news such as “Spanish silver fleet sunk” or “Plague in Algiers”, they appear presented as less important than other content.[7] What explains this is that readers felt a vested interest in the military and diplomatic maneuverings on the continent more so than dramatic but inconsequential events. It is easy to forget how young and under threat Protestantism was in the 17th century, and so updates on the Wars of Religion that might determine whether the faith would survive were highly valued by readers in Britain.

Analysing the content of these early newsbooks demonstrates why they appealed to readers. It was less a result of a detached voyeurism but instead their sense of being very much a part of and susceptible to the effects of continental politics, making them all the more hungry for every detail that the stationers of London were able to provide.

Author’s Bio: Rory Bannerman is an MLitt student in Intellectual History at the University of St Andrews. He holds an MA in History from the University of Dundee, specialising in European history during the Early Modern period.

Endnotes

[1] Folke Dahl, A bibliography of English Corantos and Periodical Newsbooks 1620-1642. (London: The Bibliography Society, 1952) No.38, 1622. APR 17.

[2] Ibid, No.75, 1622 SEPT 14.

[3] Ibid, No.46, 1622 JUNE 5

[4] Ibid, No.98, 1623 FEB 11

[5] Jayne E.E. Boys, London’s News Press and the Thirty Years’ War (Woodbridge: The Boydell press, 2011) pp.53-4

[6] Folke Dahl, A bibliography of English Corantos and Periodical Newsbooks 1620-1642. (London: The Bibliography Society, 1952), No.98, 1623 FEB 11

[7] Ibid. No.113, 1623 MAY 26

Further Reading List

- Jayne E E Boys. London’s News Press and the Thirty Years War. (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2011).

- Andrew Pettegree. The Invention of News. (London: Yale University Press, 2015).

- Joad Raymond. Pamphlets and Pamphleteering in Early Modern Britain. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003).