By Pelayo Fernández García.

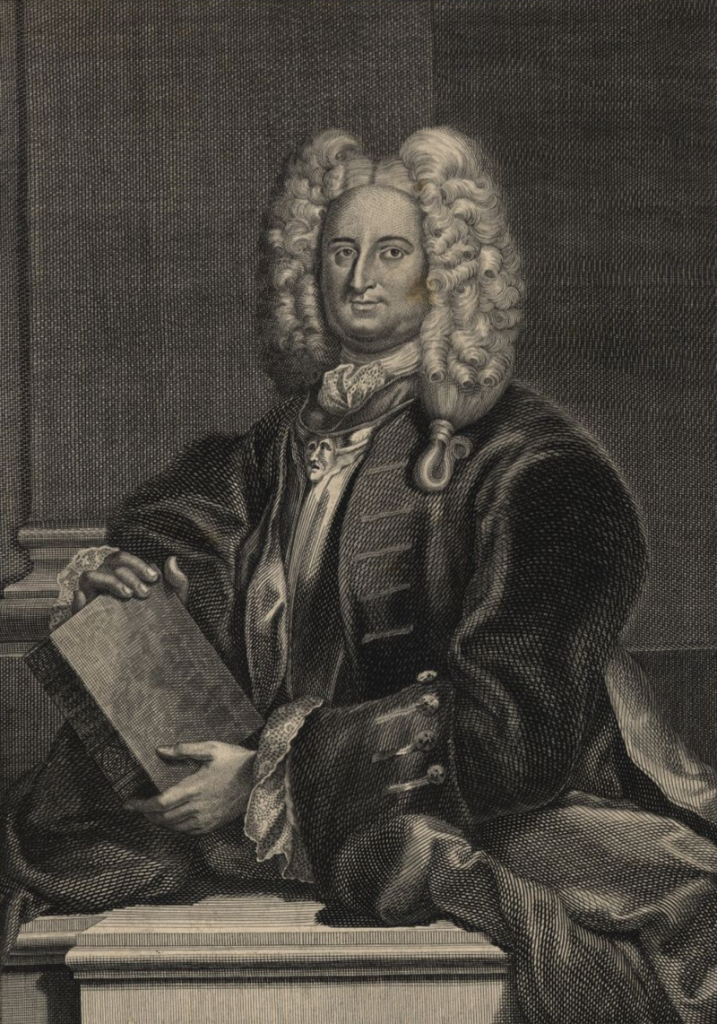

Don Álvaro de Navia Osorio, third Marquis of Santa Cruz de Marcenado was born in Puerto de Vega (Asturias, Spain) on December 19, 1684. [1] His family influences allowed him to become maestre de campo (later colonel) of the Principality of Asturias’ tercio (later regiment), shortly before the beginning of the War of Spanish Succession (1700-1714). [2]

Fighting in favour of the Bourbon side through the Iberian Peninsula, he left the leadership of the Asturian regiment, being appointed inspector of the Andalusian troops. [3] In 1717, he participated in the invasion of Sardinia, in a context of recovering by force the old Italian territories lost after Utrecht. Don Álvaro was appointed governor of Cagliari in Sardinia. [4]

But after the Quadruple Alliance (the Holy Roman Empire, the kingdoms of France and Great Britain, and the United Provinces of the Netherlands) Philip V forced Don Álvaro to abandon his new dominions, the Marquis found himself in an uneasy position. During the Spanish occupation of Sardinia, the military authorities had seized a number of artillery canons from the island, and the end of the war forced Spain to return it or pay its corresponding value. In the meantime, the Marquis was required to remain on the island as a hostage and guarantee of Spanish responsibility. [5]

Although his freedoms were not particularly restricted and he was never imprisoned, the Marquis came into conflict with the new governor, Baron of Saint Remy. The Baron feared that the Marquis conspired in Sardinian territory to favour a possible return of Spanish forces. Alleged rudeness from the Baron to the Marquis’ family and the Marquis himself, Don Álvaro asked Victor Amadeus II of Savoy, King of Sardinia, the grace for permission to move to Turin, to continue his period as hostage under the King’s authority in the Piedmontese capital. [6]

This foreign court was of special cultural effervescence, and the Marquis began to shape his own personal projects. In this way, during the 1720s, he wrote something that he had been considering since his youth. It was a multi-volume military treatise, entitled Military Reflections, and published mainly in Turin between 1724 and 1727. To these first 10 volumes of the work was added an eleventh in Paris, in 1730. [7] At that time, Marquis had already been freed from his hostage status and transferred to France.

Because his time in the Piedmont capital was not limited only to writing business, for several years, Marcenado acted as an unofficial diplomatic liaison between the Courts of Turin and Madrid. [8] This would lead to his appointment as second plenipotentiary at the Congress of Soissons, where a plethora of European powers were summoned to try to resolve their differences peacefully. His years as a diplomat in France were turbulent and not always fruitful. [9] Furthermore, the costs of living as a Spanish representative in a foreign court, first in Turin and later in Soissons and Paris, led him to be in debt. [10]

Marcenado, who always yearned for a return to military life so that he could put his theories into practice, was relieved when he was reclaimed by Spain in 1731, and assigned to operations in North Africa. Derived from these, after the taking of Oran, the city was put under the military authority of the Marquis. Unfortunately, he would die not long after (on November 21, 1732) during an ambush, fighting off the attack of the Algerian forces. [11]

Soon after, his latest project was published, an economic treatise titled Political-economic-monarchical Rhapsody. [12] Others could not be carried out due to lack of time or institutional support, such as his idea of a Universal dictionary, an encyclopedic initiative that he was unable to carry out on his own. [13] But undoubtedly his greatest legacy was his Military reflections, which became a work of reference for the Europe of his time, being republished several times, and translated, partially or totally, into five more languages than their original Spanish (French, English, Italian, German and Polish). [14]

From the nineteenth century onward, however, Marcenado and his work have mostly been relegated to commemorations, tributes and studies from his native country, despite the fact that some academics consider him one of the most important military authors of his time. [15] My own research is aimed at studying the true worth of his entire work, among other objectives.

For example, the study of their social networks through their correspondence and other documents, would determine not only their authentic diplomatic role in their international representations, but also his cultural and social support network that may have influenced his work.

Likewise, and in contrast to this apparent dissociation from his study beyond Spain, I also seek to study the social and political structures that have kept Marcenado’s legacy alive within the borders of my own country. The institutional and military support has been clear, especially in the celebration of the anniversaries of the birth of the Marquis. My goal is also to study its evolution and contextualize the propaganda created around the author and his work.

Author’s Bio: Pelayo Fernández García is a PhD candidate at the University of Oviedo and Versailles, with a Severo Ochoa predoctoral grant for research and teaching, and currently a visiting researcher at the University of Glasgow through a Santander Bank mobility grant. His research interests include war in the early modern period, especially from a cultural point of view, and the study of correspondence and social networks. Following those lines he has published Las Reflexiones militares del marqués de Santa Cruz de Marcenado y su influencia más allá de las fronteras nacionales (2015) and El I conde de Toreno: logística y economía de guerra en la crisis de la monarquía hispánica (2018), two monographs awarded respectively by the Spanish Ministry of Defense and its Army.

Acknowledgements: This research has been financed by the Santander Bank mobility grant.

Select Further Readings:

- Díaz Álvarez, Juan, Ascenso de una casa asturiana: los Vigil de Quiñones, marqueses de Santa Cruz de Marcenado (Oviedo, 2006).

- Díaz Álvarez, Juan, ‘Los marqueses de Santa Cruz de Marcenado y sus actividades castrenses (siglos XVII-XIX)’ in Faya Díaz, María Ángeles and Martínez-Radío, Evaristo (coords.), Nobleza y ejército en la Asturias de Edad Moderna (Oviedo, 2008).

- Galmés de Fuentes, Álvaro, Las ideas económicas del tercer marqués de Santa Cruz de Marcenado (Madrid, 2001).

- Heuser, Beatrice, The Evolucion of Strategy. Thinking War from Antiquity to the Present (Cambridge, 2010).

- IDEA, El marqués de Santa Cruz de Marcenado 300 años después (Oviedo, 1985),

Endnotes

[1] Madariaga y Suárez, Juan de, Vida y escritos del marqués de Santa Cruz de Marcenado, (Madrid, 1886), pp. 11-12.

[2] Salas, Javier de, ‘Biografía de D. Álvaro de Navia Osorio, Marqués de Santa Cruz y Vizconde de Puerto’, in Navia-Osorio, Álvaro de, Reflexiones militares (Barcelona, 1885), pp. VII-XI.

[3] Madariaga y Suárez, Juan de, Vida y escritos del marqués de Santa Cruz de Marcenado, (Madrid, 1886), pp. 94-95.

[4] Carrasco-Labadía, Miguel, El marqués de Santa Cruz de Marcenado: noticias históricas de su vida, sus escritos y la celebración de su centenario en 1884 (Madrid, 1889), pp. 15-16.

[5] Altolaguirre and Duvale, Ángel, Biografía del marqués de Santa Cruz de Marcenado (Madrid, 1885), pp. 17-18.

[6] Fuertes Acevedo, Máximo, Vida y escritos del marqués de Santa Cruz de Marcenado, (Madrid, 1886), p. 26.

[7] Salas, Javier de, ‘Biografía de D. Álvaro de Navia Osorio, Marqués de Santa Cruz y Vizconde de Puerto’, in Navia-Osorio, Álvaro de, Reflexiones militares (Barcelona, 1885), pp. XII-XIII.

[8] Madariaga y Suárez, Juan de, Vida y escritos del marqués de Santa Cruz de Marcenado, (Madrid, 1886), pp. 114-116.

[9] Salas, Javier de, ‘Biografía de D. Álvaro de Navia Osorio, Marqués de Santa Cruz y Vizconde de Puerto’, in Navia-Osorio, Álvaro de, Reflexiones militares (Barcelona, 1885), pp. XII-XIII.

[10] Archivo General de Simancas, Simancas, Estado, leg. 7540.

[11] Fuertes Acevedo, Máximo, Vida y escritos del marqués de Santa Cruz de Marcenado, (Madrid, 1886), pp. 27-30, 37-46.

[12] Galmés de Fuentes, Álvaro, ‘La Rapsodia económica del marqués de Santa Cruz de Marcenado’, in Centro de Estudios del Siglo XVIII (ed.); II Simposio sobre el Padre Feijoo y su siglo: (ponencias y comunicaciones), v. 2 (Oviedo, 1983), p. 136.

[13] See Ruiz de la Peña Solar, Álvaro, ‘La prosa enciclopédica del marqués de Santa Cruz’ in Edad de Oro XXXI, 2012, pp. 309-321.

[14] Fernández García, Pelayo, Las Reflexiones militares del marqués de Santa Cruz de Marcenado y su influencia más allá de las fronteras nacionales (Madrid, 2015), pp. 80-88.

[15] Heuser, Beatrice, The Strategy Makers: Thoughts on War and Society from Machiavelli to Clausewitz (Cambridge, 2010), p. 126.

Image: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d1/%C3%81lvaro_de_Navia_Osorio.png/800px-%C3%81lvaro_de_Navia_Osorio.png