By Lula Murphy

On a misty morning in 1982, Argentine forces disembarked on the Falkland Islands, beginning a war with the UK that ended with a death toll of 649 Argentine soldiers, 255 British soldiers, and three islanders.[1] However, the 74-day conflict which began that 2nd April was a new chapter in an older dispute dating back to 1833, when Argentina contends that Britain usurped Argentine sovereignty by taking the islands. Thus, a pithy remark popularly attributed to legendary Argentine writer Borges that the war constituted ‘a fight between two bald men over a comb’ belies the deeply emotive power of the Falklands in Argentine society, where they are known as ‘ las Islas Malvinas ’. Moreover, the political context that created the conditions for the war and later revelations about human rights abuses deepened and complicated the processes of memory crafting that followed Argentina’s surrender on the 14th June 1982.

Between 1976-83, a brutal military dictatorship ruled Argentina. The regime kidnapped and murdered an estimated 30,000 people, often by pushing them drugged but alive out of planes on the now-infamous death flights. In this repressive period of state-sponsored terrorism, civil resistance nevertheless persisted and so maintaining some level of public approval remained relevant to managing power. By 1982, the regime was in trouble. A struggling economy and growing discontent over the unknown fate of the disappeared civilians (‘los desaparecidos’) was provoking unprecedented levels of unrest and demonstrations. In response, the Junta turned to the Falklands in order to externalise these difficulties and provide a national symbol to rally around.[2]

Ever since 1833, Argentine governments have promoted the retrieval of the Falklands using narratives of dispossession at the hands of a colonial power as part of creating a national identity. Indeed, crafting stories and designating symbols was a common technique across much of Latin America where state-formation generally preceded nation-building.[3] Thus, it was no coincidence that the Junta claimed a temporal continuity between 1833 and 1982, placing the war’s protagonists into the longer genealogy of liberators who fought colonial Spain for Argentina’s independence in the early 1800s.[4] The invocation of national heroes endowed a politically-timed invasion with the legitimacy of a great patriotic act, which seemed vindicated by an outpouring of enthusiastic civilian support when the Junta announced the military’s successful landing as a fait accompli .

Public opinion remained positive during the conflict due to the regime’s propaganda, with news headlines screaming falsehoods and illusions of imminent victory such as ‘We are still winning!’ (‘¡Seguimos ganando!’). Consequently, the Junta shocked the population with the announcement of Argentina’s surrender. Defeat both precipitated the end of the dictatorship and provoked early post-war narratives filled with anger at the regime and its deception. Many civilians also shunned returning soldiers or avoided the topic because they felt guilt at their emotional, and sometimes material, support for the war. Civilian participation was diverse, from women knitting in public for the soldiers under a banner declaring that they would do so every day until the ‘English pirates’ were definitively defeated to children donating chocolate with little notes enclosed for the soldiers- although many of the gifts were quietly siphoned off and sold.

Following the restoration of democracy in 1983, public revelations about the military dictatorship’s extent of human rights abuses added to the complexity of processing the war. The National Commission on the Disappearance of Persons (Spanish: Comisión Nacional sobre la Desaparición de Personas, CONADEP) collected vast amounts of testimony to produce a searing report documenting horrors such as torture, murder, and the theft of babies born to mothers in captivity within the clandestine detention centres.[5] The public also learned about the suffering of young conscripts, who the military sent poorly equipped to the Falkland Islands during the war, where they faced both enemy forces and abuses from their own senior officers that ranged from humiliations to summary executions.

These hard truths prompted most of Argentine society to adopt CONADEP’s mantra of ‘Never again’ (‘Nunca más’) in reference to state repression and the systematic violation of human rights, whilst public remembrance became a central part of the political landscape.[6] The work of CONADEP and the sensational Trial of the Juntas in 1985, where leading members of the regime were imprisoned in a region accustomed to impunity, transformed Argentina into a ‘global protagonist’ of transitional justice.[7]

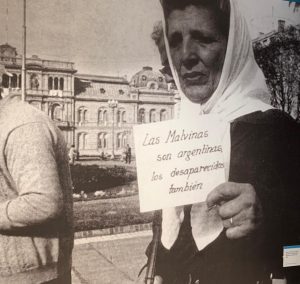

Members from the campaign group Madres de la Plaza de Mayo on a protest march in Buenos Aires, 1982. The placard reads ‘The Falklands (Malvinas) are Argentine, and the disappeared are too’. (Photo: Display in the Museo Malvinas e Islas del Atlántico Sur in Buenos Aires. The museum is located on the grounds of the ex-ESMA, the most infamous clandestine detention centre from the last dictatorship. Photo author’s own)

Reckoning with the war proved more complicated. Various protagonists such as ex-combatants, politicians, the military, and human rights groups promoted diverse ways of remembering the war. Clashing positions defined the war in ways such as a patriotic stand for Argentine sovereignty, or as a deceptive and disastrously-managed escapade. The histories, interests, and objectives of concerned parties influenced their memory discourses as they fought for the preeminence of their interpretations and sought to convince wider society that their own narratives were the only legitimate ones. Therefore, whilst defeat ended the international military conflict, it triggered ongoing domestic struggles to assign meaning.

Human rights were not the only factor that made the Falklands War a controversial memory, but they were a significant stumbling-block to the traditional jingoism that often accompanies national wartime commemorations. The wider political context of a dictatorship complicated casting the war as a patriotic venture since modern Argentine rhetoric critiqued the colonial implications of British rule and equated it to a tyranny in its own right. Accordingly, society has struggled to memorialise the war whilst condemning the dictatorship, and to commemorate the ex-combatants whilst remembering that some were conscripts and others were themselves human rights abusers within their professional military capacity. As a result, the Falklands remain an evolving but still ‘open wound’ in Argentine society.[9] Already, the nuances of collective memory with regards to the war have changed with the passage of time and the shifting prominence of the human rights agenda. No set of memories is fixed indefinitely and undoubtedly future generations will continue to debate the meaning of the Falklands War in response to new political disputes, so this wound is likely to remain painful for some time to come.

Author Bio: Lula Murphy is currently writing a thesis at Dartmouth College on the memorialisation of the Falklands/Malvinas War in Argentina 1989-2015, with a focus on the interaction of memory politics with economic ideologies. She will be presenting her research at the Latin American Studies Association (LASA) annual congress in May 2021. @lula__murphy

Further Reading

Aboy Carlés, G. ‘Populismo y democracia en la Argentina contemporánea: Entre el hegemonismo y la refundación’ in Estudios Sociales, 28(1), 2005, 125-149

Caviglia, Sergio Esteban. Malvinas : Soberanía, Memoria y Justicia : 10 de Junio de 1829 : Vol I. Argentina: Ministerio de Educación de la Provincia de Chubut, 2012

Guber, Rosana. De chicos a veteranos. Memorias argentinas de la guerra de Malvinas. La Plata: Al Margen, 2009

Jelin, Elizabeth. “Layers of Memories: Twenty Years After in Argentina” in The Politics of War Memory and Commemoration, ed. T.G. Ashplant, Graham Dawson, and Michael Roper. London: Routledge, 2000

Lessa, Francesca. Memory and Transitional Justice in Argentina and Uruguay: Against Impunity. New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2013

Novaro, Marcos and Palermo, Vicente. La Historia Reciente: Argentina en Democracia. Buenos Aires Edhasa, 2004

Perochena, Camila. ‘Una memoria incómoda. La guerra de Malvinas en los gobiernos kirchneristas (2003-2015)’ in Anuario de Historia Regional y de las Fronteras 21(2), 2016. 173-191

Robben, Antonius C. G. M. Political violence and trauma in Argentina. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005

Tandeciarz, Silvia R. ‘Citizens of Memory: Refiguring the Past in Postdictatorship Argentina’ in PMLA 122(1), 2007. 151-69

Verbitsky, Horacio. La posguerra sucia: Un análisis de la transición. Buenos Aires: Legasa, 1985

Endnotes

[1] Jimmy Burns, The Land that Lost its Heroes: How Argentina Lost the Falklands War (Bloomsbury,

2002), 323

[2] Manus I Midlarsky, The Internationalization of Communal Strife (Routledge, 1992)

[3] Elizabeth Jelin, State Repression and the Labors of Memory , trans. Judy Rein and Marcia

Godoy-Anativia (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003), 20

[4] Rosana Guber, ¿Por qué Malvinas?: De la causa nacional a la guerra absurda (Buenos Aires:

Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2012), 31

[5] CONADEP, Nunca Más, 1984

[6] Michael Humphrey and Estela Valverde, “Human Rights, Victimhood, and Impunity: An Anthropology

[7] Katherine Sikkink, “From Pariah State to Global Protagonist: Argentina and the Struggle for International Human Rights”, Latin American Politics and Society 50, no. 2008: 1-29

[8] Federico Lorenz, Las guerras por Malvinas (Buenos Aires: Edhasa, 2012)

[9] Vicente Palermo, Sal en las heridas: Las Malvinas en la cultura argentina contemporánea

(Sudamericana: Buenos Aires, 2007)

Featured Image: Piece in the Museo Malvinas e Islas del Atlántico Sur in Buenos Aires. Photo author’s own