By Pablo Pryluka

In 1972, the Club of Rome published The Limits to Growth. After signing an agreement with an MIT team, they developed a computational model that predicted the imminent collapse of planet Earth: the growing population was about to drain all the available resources and create a demographic collapse. Claiming such an apocalyptic future, the book became a best-seller and was translated to at least 30 languages.

This is a well-known story. Historians, economists, and environmental scientists have written extensively on the history of the Club of Rome and its critique of economic growth. Less familiar is the trajectory of the Bariloche Foundation (BF), an Argentine institution that launched the Latin American World Model as a response to the Club of Rome, which this essay assesses,

In March 1963, Carlos Mallmann and other Argentine scientists founded the BF. Bariloche was a small city in Patagonia, close to the Andes and surrounded by some of the most inspiring landscapes of Argentina. After completing his graduate studies and spending time in the United States, Mallmann returned to Argentina and became a researcher at the Physics Institute of Bariloche. However, he soon devised came up with a new project: the creation of a university in Bariloche, far away from Buenos Aires and other major cities.

Carlos Mallmann in Bariloche (Photo: Revista La Nación, April 2, 1972)

To set the endeavor in motion, they had to begin by raising funds. The Ford Foundation became the main source of income during the early years, together with some local private companies. By 1965, the local government of Bariloche offered land to the foundation in order to build a university campus. The project seemed to be moving ahead at full speed… but then but then the political landscape in Argentina changed abruptly in 1966.

Campus Project, designed by the studio Caudill Rowlett Scott (Photo taken from Shmidt, 2020)

In June 1966, a coup led by Lieutenant General Juan Carlos Onganía seized power. Right after, the military seized the University of Buenos Aires and persecuted political dissidents. A “brain drain” began as a consequence, with researchers and professors trying to find new academic destinations in exile.

As a side effect, the BF had the unexpected opportunity to recruit some of the most prestigious scientists in the country, especially those that could not leave the country. Far away from Buenos Aires and its radical political culture, the dictatorship did not oppose this reinsertion. In fact, quite the opposite occurred t as the BF was awarded public funding to complement the grants coming from the Ford Foundation.

In the meantime, the university project developed into something else: the BF combined graduate seminars with scientific research. Instead of the original campus, the BF rented and then bought Soria Moria, a stone house built in the 1940s and located in the outskirts of Bariloche. In this new location, the BF consolidated six departments: Biology, Social Sciences, Knowledge Transfer, Mathematics, Natural Resources and Energy, and Music. For the first time in Argentina, the BF provided an exceptional environment for projects involving people from different departments.

Soria Moria (Photo: Revista La Nación, April 2, 1972)

However, the international recognition of the BF arrived only after the 1970s. In that same year, Rio de Janeiro hosted a meeting of the Latin American members of the Club of Rome, the institution founded in 1968 by the Italian businessmen Aurelio Peccei. Concerned about the increasing pressure exerted by demographic growth on natural resources, the Club of Rome hired a scientific team from MIT to develop a prospective model. In 1970, the team led by Dennis Meadow came up with World3. The new computational model predicted the interactions between population and natural resources for the upcoming decades. The disturbing results obtained were published in The Limits to Growth: in less than a century, if nothing changed, planet Earth would face concrete limits to economic growth, after exhausting all available resources. This neo-Malthusian diagnosis awoke interest in the media and reached every corner of the globe.

Before the book came out, members of the BF came to Rio in 1970 to assist in the presentation of World3. They were shocked by the model: the demographic dynamic and economic resources were not enough to justify their economic forecast. Instead, the BF members left Rio with the impression that no model could work without taking into account political and ideological variables. In other words, this was not just a demographic question but rather a developmental one. If natural resources were under pressure, that was due to the high consumption rates in the developed world. The Third World, with high poverty rates, still had a long way to go to improve its material standard of living. Therefore, the solution should not rely on demographic controls—the economies at the core should change their developmental model and restrict consumerism.

The BF chose to create an alternative model. Between 1972 and 1974, a team headed by Amílcar Herrera and Hugo Scolnik developed the Latin American World Model (LAWM). They introduced new variables and showed that collapse was not inevitable if economic growth could slow down at the core.

The Bariloche Foundation Data Center (Photo: Courtesy of Hugo Scolnik)

In 1974, the Club of Rome invited the BF to present their preliminary findings. The event took place in Austria at the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA). . Created in 1972, IIASA provided a space for scientific cooperation between American and Soviet researchers as an attempt to placate the Cold War tensions. For three days, the BF team presented the model toa global audience that included the Nobel Laureates Tjalling Koopmans and William Nordhaus, and members of the US State Department.

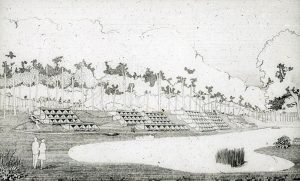

The meeting was a success. In 1976, the model’s results were published in English entitled as “Catastrophe or New Society? A Latin American World Model.” In the next five years, translations to French, German, Romanian, and Dutch appeared. However, the Spanish edition was published only in 1977 – after the English one. What had happened?

Cover of the English edition

The worldwide reputation of the BF did not go unnoticed in Argentina. In March 1976, another coup put the military in power. This time, the dictatorship used both military and paramilitary forces to set up a repressive apparatus to kidnap, murder, torture, and disappear political dissidents. In this new context, the notoriety of the BF put its members under the radar of the military intelligence. Public funding ended, and many scientists had to go into exile—among them, Herrera and Scolnik, the two heads of the LAWM.

“The Bariloche Foundation under Investigation” (Photo: La Nación, November 22, 1976)

In 1975, the BF had a total of 6 departments and 230 employees. Three years later, the BF retained only 3 working groups and hosted less than 20 workers, between staff and researchers. Although the BF survived the dictatorship (which ended in 1983), the military persecution dismantled the institution and, with it, the interdisciplinary project that had given life to the LAWM.

Coming from the south of the Global South, the history of the BF elucidates two interconnected threads. On the one hand, it shows the global nature of development and debates on economic growth in the 1960s and 1970s. On the other, this story illustrates some of the silences upon which historical narratives are built. Dismantled by a local dictatorship, the BF does not figure in most of current histories about economic development. Despite this absence, during the 1980s international institutions like the World Bank and ILO picked up many of the ideas contained in the LAWM. Their Patagonian footprint, however, disappeared in the long run—as they were presented as innovations created in the core global economies.

Author’s Bio: Pablo Pryluka is a PhD candidate in the Department of History at Princeton University. Pryluka’s main fields of interest are modern Latin American History and Global History, with a focus on social and economic history. His dissertation aims to provide a comparative analysis of patterns of consumption and inequality in Argentina, Brazil, and Chile during the state-led industrialization years (1930s-1970s). More information here.

Sources

This blog has been written based on the articles appeared on the special issue of Pasado Abierto, 11 (2020): Rémoras de un proyecto olvidado: La Fundación Bariloche y la Argentina del Desarrollo.

- “La Universidad de Utopía”. Un proyecto para el campus de la Fundación Bariloche (1962-1966), by Claudia Shmidt.

- Sistemas de estratificación, migraciones y desarrollo en las publicaciones del Departamento de Sociología de la Fundación Bariloche (1967-1973), by Hernán Comastri.

- “Una futura Heidelberg argentina”: el itinerario de la Fundación Bariloche (1963-1978), by Pablo Pryluka.

- Los límites del desarrollo rebatidos desde el Sur. Circulación, representaciones y olvidos alrededor del Modelo Mundial Latinoamericano, by Ana Grondona.

Further Reading

Arndt, H. (1987). Economic development: The history of an idea. University of Chicago Press.

Braslavsky, S., & Carnota, R. (2018). “Operativo Rescate”: La Fundación Ford y la emigración posterior a la Noche de los Bastones Largos (J. Morales Martin & F. Quesada, Eds.). Santiago: Ediciones UCSH.

Caria, S., & Domínguez, R. (2018). Raíces latinoamericanas del otro desarrollo: Estilos de desarrollo y desarrollo a escala humana. América Latina En La Historia Económica, 25(2), 175–209.

Feld, A. (2015). Ciencia y política(s) en la Argentina, 1943-1983. Bernal: Universidad Nacional de Quilmes Editorial.

Feld, A. (2019). Organización disciplinaria, asistencia extranjera y agendas de investigación en la física argentina de los “años dorados.” Pasado Abierto, 10, 64–102.

Herrera, A. O. (Ed.). (2004). ¿Catastrofe o nueva sociedad?: Modelo Mundial Latinoamericano. Ottawa: International Development Research Centre.

Hodge, J. M. (2015). Writing the History of Development (Part 1: The First Wave). Humanity: An International Journal of Human Rights, Humanitarianism, and Development, 6(3), 429–463.

Hurtado de Mendoza, D. (2010). La ciencia argentina: Un proyecto inconcluso,1930-2000. Buenos Aires: Edhasa.

Macekura, S. J. (2015). Of limits and growth: The rise of global sustainable development in the twentieth century. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Macekura, S. J. (2020). The Mismeasure of Progress: Economic Growth and Its Critics. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Meadows, D. H., Meadows, D. L., Randers, J., & Behrens III, W. W. (1972). The Limits to growth; a report for the Club of Rome’s project on the predicament of mankind. New York: Universe Books.

Sauro, S. (2015). Cosmovisiones, utopías y polémicas a propósito del Club de Roma y del modelo mundial latinoamericano. Revista de La Red de Intercátedras de Historia de América Latina Contemporánea, 2(2), 28–45.

Schmelzer, Matthias. (2016). The Hegemony of Growth. The OECD and the Making of the Economic Growth Paradigm. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

– (2017). “‘Born in the corridors of the OECD’: the forgotten origins of the Club of Rome, transnational networks, and the 1970s in global history,” Journal of Global History, 12: 1.

Feature Image: Carlos Mallmann in Bariloche (Photo: Revista La Nación, April 2, 1972)