By Inaya Khan

Colonialism not only encouraged the emigration of white populations from Europe to Africa but also circulations of such populations within the African continent itself. Kenya was formally annexed as a Crown colony in 1920 – a twentieth century experiment in the exertion of British hegemony, predominantly through agricultural settlement rather than trade. The colony was established in the wake of a world war, and in light of ‘lessons learnt’ from older and more established British dominions with dominant settler populations, such as Canada and South Africa. The only trouble was that the settlers who were handpicked by the British government to populate this colony were too rich and upper-class to have had any actual farming experience. In order to solve this problem, Sir Charles Eliot invited Afrikaner farmers from South Africa (then part of the British Empire) in 1903 to settle in Kenya and develop the colony’s agricultural sector – an idea which worked.

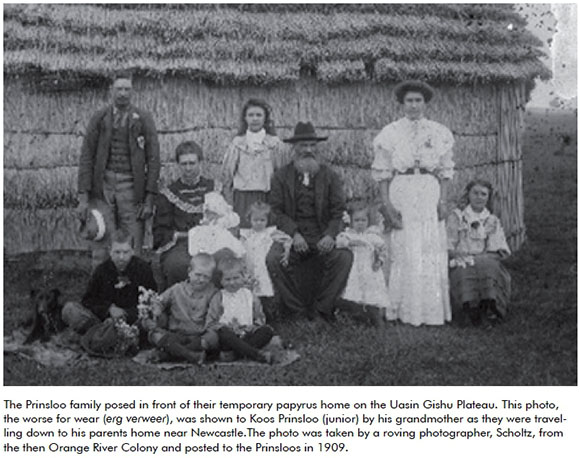

South Africans slowly established themselves in the farming and business sectors, as well as in the civil services of the colonial administration. The Afrikaner community carved out an identity independently of the British community with whom there remained a social gulf. The British considered the Afrikaners in Kenya to represent an ‘inferior white race’ and to be unable to uphold white prestige in quite the same vein as their Anglo-Saxon contemporaries. The Afrikaners were also often illiterate and many of them lived up-country in the Uasin Gishu plateau rather than Nairobi. British settlers also looked down upon the Afrikaners because of their hardy lifestyle which centred around manual labour and hunting, and the fact that they often served as farm managers for wealthy Europeans. Urban South African businessmen who were wealthy easily integrated into the British community in Nairobi, and gained privileged access to metropolitan politicians through their social contacts and positions of leadership within the white settler community. The Afrikaner community also maintained historical links with South African Prime Ministers like JBM Hertzog and Dr. Malan, with whom they communicated on issues of interest.

However, the prospect of Kenyan independence in 1963 convinced the Afrikaners that there was no future for them in view of the independent Kenyan state’s hostile relations with South Africa. South Africans believed their unpopularity with black Africans made them vulnerable to attack. The end of British rule in Kenya had different implications for the three different groups of South Africans in Kenya—the Afrikaner farmers’ community, those working for firms, and with business interests in Nairobi, and those employed in the service of the Crown. The Afrikaner farmers decided, early on, to return to South Africa but were unwilling to do so empty- handed, while the concerns of the two urban groups did not revolve around land or compensation but rather around citizenship and residency issues — the right to remain and work in Kenya.

In the early 1960s, the flight of the pied noirs from Algeria and Belgian refugees from the Congo invoked images of panic, chaos, coercion, and a loss of confidence in the idea of multiracialism as an implementable policy in decolonized states. The Afrikaners grew 60-70% of Kenya’s wheat and owned around 500,000 acres of land in Kenya. The community decided to use the threat of exodus and all its attendant negative consequences, to gain economic compensation for their farms and citizenship concessions for their children and themselves. The Afrikaners’ demands were supported by the British community who had previously maintained a social distance from them but now chose to present a united front of white minorities against the tide of African majoritarianism.

The three state actors, Britain, South Africa, and Kenya used this opportunity to define and reinforce their state ideology in opposition to one other in an intra-African theatre. South Africa attempted to establish itself as the preferred white man’s dominion in Africa, while Kenya used it to entrench its anti-apartheid position and made it clear that Afrikaners who renounced apartheid were welcome to stay on in Kenya. Britain prioritised the interests and demands of the British settlers in Kenya as well as its comprehensive strategic alliance with the new Kenyan government, and made concessions to Afrikaners within this framework.

How bad was it really for the South Africans— were they being racist and paranoid or was there actual cause for concern? How did the South Africans use their privilege to get concessions? What did the Kenyan and South African states make of this political moment? What was the response of both the British government and the bureaucrats who ran the Empire from Whitehall? Most importantly of all, how does all of this relate to the wider question of decolonization? These are some of the questions my recent article in The Historical Journal , Kenya’s South Africans and the Politics of Decolonization, answers.

Feature Image: Cloete, Elsie. “Going on Safari: the Tale of Two Koos Prinsloos.” Tydskr. letterkd. Vol. 54, No. 1 (2017) p. 5-33. http://www.scielo.org.za/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0041-476X2017000100001