By Patrick van der Geest. @ideesdupasse

The credit crisis of 1772-1773 is perhaps the least known financial crisis of the eighteenth century. It took place between two infamous events: the banking crisis of 1763 and the economic turmoil of the American Revolutionary War. Yet it is just as, if not more, historically significant, because it occurred at a watershed moment in the development of banks, financial institutions, and the global economy.[1]

It is generally assumed that the London bank Neale, James, Fordyce, and Down precipitated the crisis, having lost £300,000 on speculation in East India Company (EIC) stock. Its partner, Alexander Fordyce, then absconded to France to avoid debt repayment.[2] The bank’s collapse caused panic in London, inducing bank runs and a liquidity crisis.[3] The restriction of credit and the disruption in the bills of exchange market that followed quickly spread the crisis further. It bankrupted almost every private bank in Scotland and wreaked havoc from Europe’s financial centre, Amsterdam, to Hamburg, St. Petersburg, Genoa, Stockholm, and Paris.[4]

Towards the end of 1773, the crisis seemed to be over and the financial markets recovered.[5] The Bank of England had a significant role in expediting financial recovery by intervening in the bills of exchange market and extending short-term loans to cash-strapped banks.[6] The impact of the crisis on the real economy is still debated, as growth rates rebounded to pre-crisis levels by 1774-1775.[7]

Similarly, scholars are divided over the underlying causes of this crisis. Some argue there were insufficient financial regulations in place, whereas others argue the opposite. Financial institutions either choked economic development, or they failed to direct the financial sector.[8] Increased interdependence between banking houses either increased market volatility, or the expansion of the banking system created economic opportunities.[9] Political squabbling over the future of the EIC either increased stock volatility, or its directors manipulated stock in their own favour.[10] The list of controversies goes on.

However, all elements of this historiographical debate have one thing in common: they centre around Great Britain. Departing from the assumption that the fall of Neale, James, Fordyce, and Down precipitated the crisis, scholars seem to have zeroed in on market conditions in Britain alone. This narrow focus has obscured any contribution that puts the crisis in a broader European, or indeed global, perspective.[11] Moreover, it has prevented identifying external factors as underlying causes of this crisis.[12] I therefore propose an alternative, more global approach.

What if the beginnings of the crisis did not lie within the walls of a London bank, but in the colonial periphery, with an insignificant market player? Let us assume he was a Dutch planter on the Danish Caribbean island of Saint Croix. The following fictional reconstruction is based on my research on contemporary mortgage funds by Amsterdam banking houses for planters in the West Indies.[13]

Like many of his peers in the booming plantation economies of the Americas, this hypothetical planter would have taken out a mortgage to acquire his property, tools and materials, and expensive enslaved labour force.[14] However, at some point, a modest harvest and falling cash crop prices in Europe would have forced him to resort to short-term loans to pay his mortgage instalments. Thus, with every passing season, our man would have paid interest on more loans, becoming trapped in a cycle of debt.[15]

To contemporaries, this would have been unproblematic, as significant personal debts were common at the time. It is likely that his managed personal liquidity and dutiful interest payments garnered him trust among partners and creditors.[16] Until, after several years, lightning struck. Unable (or unwilling) to continue, our planter claimed insolvency.

This sudden payment stoppage would have paralysed his creditors because they, too, had due debts, as did their debtors, et cetera. The early modern European economy was based not on credit, but on debt – everyone owed everyone else. This system facilitated a continuous circulation of capital through the bills of exchange market, in effect creating liquidity. It also facilitated the movement of capital across borders and oceans, and sustained long-distance economic ties.[17] However, once debts were called in, this complex mosaic unravelled.

I argue that one single, unknown actor outside Great Britain, like our hypothetical planter on Saint Croix, initially caused the credit crisis of 1772-1773. His insolvency, by way of a domino effect, brought the transnational bills of exchange market to a grinding halt. In 1772, financial markets were self-organised networks of individuals, who kept complex economic relations with individuals overseas. Through the bills of exchange market, the spread of illiquidity could spark a panic that would, in turn, affect Europe’s major financial markets.[18]

Such a chain of events, I believe, must have preceded the above mentioned events in London. It would ultimately prevent Neale, James, Fordyce, and Down from turning to the bills of exchange market to compensate for its losses. By then, that market would already have been disrupted by a crisis originating beyond Britain’s shores.

Author’s Bio: Patrick van der Geest (1995) is finishing his degree in Colonial and Global History at Leiden University, focusing on the Scots-Dutch banking house Hope & Co. He is currently writing his master’s thesis on their role in the credit crisis of 1772-1773.

Bibliography

Bowen, H.V. ‘Investment and Empire in the Later Eighteenth Century: East India Stockholding, 1756–1791’, Economic History Review 42:2 (1989) 186-206.

––––––, ‘Lord Clive and Speculation in East India Stock, 1766’, Historical Journal 30:4 (1987) 905-920.

––––––, The Business of Empire: The East India Company and Imperial Britain, 1756–1833 (Cambridge 2006).

Checkland, S.G., Scottish Banking: A history, 1695-1973 (Glasgow & London 1975).

Coffman, D.D., et al. (eds.), Questioning Credible Commitment: Perspectives on the Rise of Financial Capitalism (Cambridge 2013).

De Jong-Keesing, E.E., De economische crisis van 1763 te Amsterdam (Amsterdam 1939).

Elofson, W.M., ‘The Rockingham Whigs in Transition: The East India Company Issue 1772–1773’, English Historical Review 104:413 (1989) 947-974.

Gervais, P., ‘Mercantile Credit and Trading Rings in the Eighteenth Century’, Annales HHS 67:4 (2012) 693-730.

Goodspeed, T.B., Legislating Instability: Adam Smith, Free Banking, and the Financial Crisis of 1772 (Cambridge & London 2016).

Hancock, D., ‘“Domestic Bubbling”: Eighteenth-Century London Merchants and Individual Investment in the Funds’, Economic History Review 47:4 (1994) 679–702.

Henderson, W.O., ‘The Berlin Commercial Crisis of 1763’, The Economic History Review 15:1 (1962) 89-102.

Hoonhout, B., ‘The crisis of the subprime plantation mortgages in the Dutch West Indies, 1750-1775’, Leidschrift 28:2 (2013) 85-99.

––––––, Subprime plantation mortgages in Suriname, Essequibo and Demerara, 1750-1800: On Manias, Ponzi Processes and Illegal Trade in the Dutch negotiatie system (Master’s thesis, Leiden University, 2012).

Hoppit, J., ‘Financial Crises in 18th Century England’, Economic History Review, 39:2 (1986) 39–58.

James, J.A., ‘Panics, Payments Disruptions and the Bank of England before 1826’, Financial History Review 19:3 (2012) 289-309.

Kosmetatos, P., Financial contagion and market intervention in the 1772-3 credit crisis (Cambridge Working Papers in Economic and Social History No. 21 2014).

––––––, The 1772-73 British Credit Crisis (Cham 2018).

––––––, ‘The Credit Crisis of 1772–73 in the Atlantic World’, in: D. Coffman et al., The Atlantic World (Abingdon 2014) 491-509.

Koudijs, P., ‘‘Those Who Know Most’: Insider Trading in 18th c. Amsterdam’, Journal of Political Economy 123:6 (2015) 1356-1409.

Koudijs P. & H.-J. Voth, ‘Leverage and Beliefs: Personal Experience and Risk Taking in Margin Lending’, American Economic Review 106:11 (2016) 3367-3400.

Lovell, M.C., ‘The Role of the Bank of England as Lender of Last Resort in the Crises of the Eighteenth Century’, Explorations in Entrepreneurial History 10 (1957) 8-21.

Marzagalli, S., ‘Opportunités et contraintes du commerce colonial dans l’Atlantique français au XVIIIe siècle : le cas de la maison Gradis de Bordeaux’, Outre-mers 96:362-363 (2009) 87-110.

Menkis, R., The Gradis family of eighteenth century Bordeaux: A social and economic study (PhD dissertation, Brandeis University, 1988).

Neal, L., The Rise of Financial Capitalism: International Capital Markets in the Age of Reason (Cambridge 1990).

Power, O., Irish planters, Atlantic merchants: the development of St. Croix, Danish West Indies, 1750-1766 (Galway 2011).

Pressnell, L.S., Country Banking in the Industrial Revolution (Oxford 1956).

Saville, R., Bank of Scotland: A History, 1695-1995 (Edinburgh 1996).

Schnabel, I., & H.S. Shin, ‘Liquidity and contagion: the crisis of 1763’, Journal of the European Economic Association 6 (2004) 929-968.

Sechrest, L.J., ‘Free Banking in Scotland: A Dissenting View’, Cato Journal 10:3 (1991) 799-808.

––––––, ‘White’s Free-Banking Thesis: A Case of Mistaken Identity’, Review of Austrian Economics 2 (1988) 247-257.

Sheridan, R.B., ‘The British Credit Crisis of 1772 and The American Colonies’, The Journal of Economic History 20:2 (1960) 161-186.

Sutherland, L.S., The East India Company in Eighteenth-Century Politics (Oxford 1952).

Trivellato, F., The Familiarity of Strangers: The Sephardic Diaspora, Livorno, and Cross-Cultural Trade in the Early Modern Period (New Haven & London 2009).

––––––, The Promise and Peril of Credit: What a Forgotten Legend about Jews and Finance Tells Us about the Making of European Commercial Society (Princeton 2019).

Van Rijckeghem, C., & B. Weder, ‘Sources of Contagion: Is it Finance or Trade?’, Journal on International Economics 54 (2001) 293–308.

White, L.H., ‘Antifragile Banking and Monetary Systems’, Cato Journal 33:3 (2013) 471-484.

––––––, ‘Banking without a Central Bank: Scotland before 1844 as a ‘Free Banking’ System’, in F. Capie & G.E. Wood (eds.), Unregulated Banking: Chaos or Order? (London 1991) 37-62.

––––––, ‘Scottish Banking and the Legal Restrictions Theory: A Closer Look’, Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking 22:4 (1990) 526-536.

Endnotes

[1] P. Kosmetatos, The 1772-73 British Credit Crisis (Cham 2018) 23-24, 298.

[2] T.B. Goodspeed, Legislating Instability: Adam Smith, Free Banking, and the Financial Crisis of 1772 (Cambridge & London 2016) 1-3.

[3] L. Neal, The Rise of Financial Capitalism: International Capital Markets in the Age of Reason (Cambridge 1990) 170-171.

[4] Kosmetatos, The 1772-73 British Credit Crisis, 175.

[5] P. Kosmetatos, ‘The Credit Crisis of 1772–73 in the Atlantic World’, in: D. Coffman et al., The Atlantic World (Abingdon 2014) 491-509: 500-501.

[6] Kosmetatos, The 1772-73 British Credit Crisis, 8; Ibid., Financial contagion and market intervention in the 1772-3 credit crisis (Cambridge Working Papers in Economic and Social History No. 21 2014).

[7] Ibid., The 1772-73 British Credit Crisis, 258-271.

[8] cf. J.A. James, ‘Panics, Payments Disruptions and the Bank of England before 1826’, Financial History Review 19:3 (2012) 289-309; M.C. Lovell, ‘The Role of the Bank of England as Lender of Last Resort in the Crises of the Eighteenth Century’, Explorations in Entrepreneurial History 10 (1957) 8-21; L.H. White, ‘Antifragile Banking and Monetary Systems’, Cato Journal 33:3 (2013) 471-484; Ibid., ‘Banking without a Central Bank: Scotland before 1844 as a ‘Free Banking’ System’, in F. Capie & G.E. Wood (eds.), Unregulated Banking: Chaos or Order? (London 1991) 37-62; Ibid., ‘Scottish Banking and the Legal Restrictions Theory: A Closer Look’, Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking 22:4 (1990) 526-536; L.J. Sechrest, ‘Free Banking in Scotland: A Dissenting View’, Cato Journal 10:3 (1991) 799-808; Ibid., ‘White’s Free-Banking Thesis: A Case of Mistaken Identity’, Review of Austrian Economics 2 (1988) 247-257.

[9] cf. J. Hoppit, ‘Financial Crises in 18th Century England’, Economic History Review, 39:2 (1986) 39-58; C. van Rijckeghem, & B. Weder, ‘Sources of Contagion: Is it Finance or Trade?’, Journal on International Economics 54 (2001) 293-308; D.D. Coffman, et al. (eds.), Questioning Credible Commitment: Perspectives on the Rise of Financial Capitalism (Cambridge 2013); D. Hancock, ‘“Domestic Bubbling”: Eighteenth-Century London Merchants and Individual Investment in the Funds’, Economic History Review 47:4 (1994) 679-702.

[10] cf. H.V. Bowen, The Business of Empire: The East India Company and Imperial Britain, 1756–1833 (Cambridge 2006); Ibid., ‘Investment and Empire in the Later Eighteenth Century: East India Stockholding, 1756–1791’, Economic History Review 42:2 (1989) 186-206; Ibid., ‘Lord Clive and Speculation in East India Stock, 1766’, Historical Journal 30:4 (1987) 905-920; L.S. Sutherland, The East India Company in Eighteenth-Century Politics (Oxford 1952); W.M. Elofson, ‘The Rockingham Whigs in Transition: The East India Company Issue 1772–1773’, English Historical Review 104:413 (1989) 947-974.

[11] Studies approaching the 1763 banking crisis from a broader, European perspective have found complex transnational credit relations, thereby uncovering connections that precipitated this crisis. Viz. E.E. de Jong-Keesing, De economische crisis van 1763 te Amsterdam (Amsterdam 1939); I. Schnabel & H.S. Shin, ‘Liquidity and contagion: the crisis of 1763’, Journal of the European Economic Association 6 (2004) 929-968; W.O. Henderson, ‘The Berlin Commercial Crisis of 1763’, The Economic History Review 15:1 (1962) 89-102.

[12] P. Koudijs and H.-J. Voth suggest that investors in Amsterdam precipitated the crisis through speculation in EIC and Bank of England stock. Viz. P. Koudijs, ‘‘Those Who Know Most’: Insider Trading in 18th c. Amsterdam’, Journal of Political Economy 123:6 (2015) 1356-1409; P. Koudijs & H.-J. Voth, ‘Leverage and Beliefs: Personal Experience and Risk Taking in Margin Lending’, American Economic Review 106:11 (2016) 3367-3400. R.B. Sheridan has also published a relevant article on the relationship between the credit crisis and the Thirteen Colonies. Viz. R.B. Sheridan, ‘The British Credit Crisis of 1772 and The American Colonies’, The Journal of Economic History 20:2 (1960) 161-186.

[13] ‘Hope to the Rescue? The relations between Hope & Co. and Lever & De Bruine regarding two negotiaties in the Danish West Indies, 1768-1777’, currently under preparation for publication in Itinerario.

[14] O. Power, Irish planters, Atlantic merchants: the development of St. Croix, Danish West Indies, 1750-1766 (Galway 2011) 1-6, 13-16.

[15] B. Hoonhout, Subprime plantation mortgages in Suriname, Essequibo and Demerara, 1750-1800: On Manias, Ponzi Processes and Illegal Trade in the Dutch negotiatie system (Master’s thesis, Leiden University, 2012) 14-21.

[16] B. Hoonhout, ‘The crisis of the subprime plantation mortgages in the Dutch West Indies, 1750-1775’, Leidschrift 28:2 (2013) 85-99: 87-88.

[17] cf. F. Trivellato, The Familiarity of Strangers: The Sephardic Diaspora, Livorno, and Cross-Cultural Trade in the Early Modern Period (New Haven & London 2009); Ibid., The Promise and Peril of Credit: What a Forgotten Legend about Jews and Finance Tells Us about the Making of European Commercial Society (Princeton 2019); R. Menkis, The Gradis family of eighteenth century Bordeaux: A social and economic study (PhD dissertation, Brandeis University, 1988); S. Marzagalli, ‘Opportunités et contraintes du commerce colonial dans l’Atlantique français au XVIIIe siècle : le cas de la maison Gradis de Bordeaux’, Outre-mers 96:362-363 (2009) 87-110; P. Gervais, ‘Mercantile Credit and Trading Rings in the Eighteenth Century’, Annales HHS 67:4 (2012) 693-730.

[18] Kosmetatos, The 1772-73 British Credit Crisis, 176-177, 231; Ibid., ‘The Credit Crisis of 1772–73 in the Atlantic World’, 491-492.

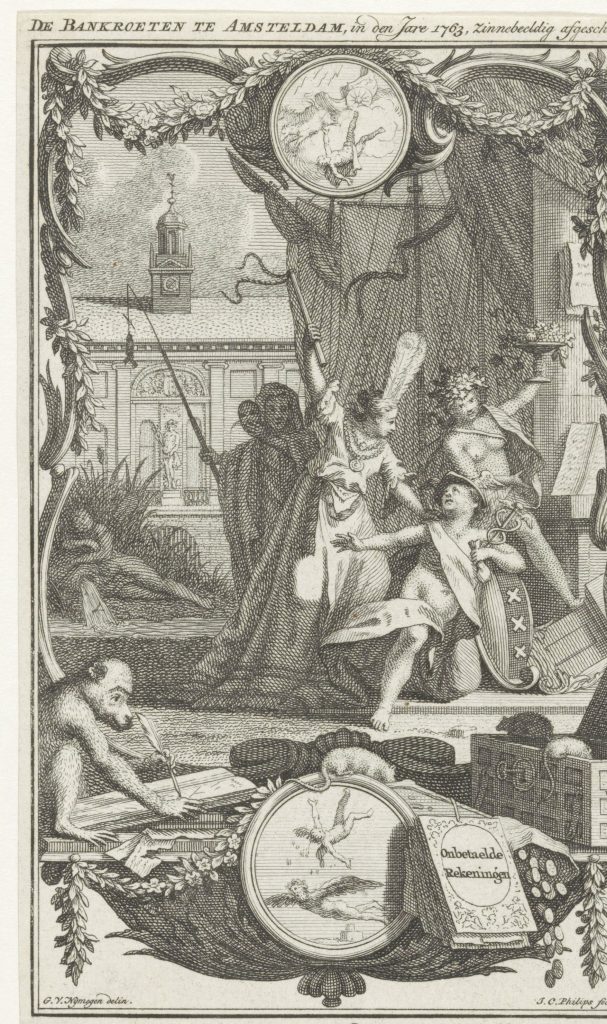

Feature Image: https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/collection/RP-P-2016-1162.

Allegorical etching of the Amsterdam banking crisis of 1763 by Jan Caspar Philips and Gerard van Nijmegen. Amsterdam’s commerce, depicted as the Roman god Mercury, is abused by Hoogmoed (Pride) and Weelde (Opulence), with Bedrog (Fraud) standing behind the abusers. In the foreground one can see an empty coffer covered in rats, a bundle of unpaid bills, a money bag with its contents falling out, and a monkey surrounded by torn paper striking through accounts in the ledgers. In the background a figure described as ‘V God’ lies despondently on top of his jug, and dark clouds gather over the Amsterdam Stock Exchange. Depicted in the two circles are the Greek god Phaethon (above) and Daedalus and his son, Icarus (below). Both Phaethon and Icarus are seen falling to Earth.