By Jennifer Faith Gray

In 1714, Captain George Winter of the Mary transhipped a cargo of 111 enslaved persons who had been purchased in Barbados to York River, Virginia, where enslaved labour was used to facilitate extensive tobacco cultivation. In the same year, Captain Robert Benn of the Charles transhipped a cargo of 177 enslaved persons who had been purchased in Jamaica to Cartagena to satisfy labour demands in the Spanish Americas.[1] These voyages are examples of the intra-American slave trade. Between 1660 and 1730, the intra-colonial slave trade to North America was dominated by Barbados and Jamaica, while the inter-imperial slave trade to Spanish America operated largely out of Curaçao and Jamaica and was characterised by a series of asiento contracts.[2]

In the British North American colonies of Virginia, Carolina, Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Connecticut, the principal hub of transhipment for enslaved persons was Barbados.[3] Virginian demand far outweighed that of other British American colonies, with Barbadian slave merchants transhipping 2,503 enslaved persons to the plantation colony between 1660 and 1730.[4] Virginia acquired a smaller number of enslaved persons from the British hub of Jamaica, from where it imported 572 enslaved Africans between 1660 and 1730.[5] This pattern follows for Carolina, Pennsylvania and New Jersey, while Connecticut supplemented transshipments from Barbados with additional transportations from New York.

In Rhode Island, Massachusetts and New York, Jamaica was the primary hub of transhipment of enslaved persons. From 1660 to 1739, more than 2,000 slaves were shipped to New York from Jamaica on 197 voyages.[6] The intra-American slave trade to New York offered a return of not only specie, but of essential provisions. This is significant as the trading of enslaved persons for goods and crops emphasises the integral place the slave trade occupied in upholding the plantation system and colonial economy, while also illuminating the evisceration of enslaved people’s humanity in a society where they were traded as a form of currency.

Spanish American colonies were greatly reliant on the intra-American slave trade, as a result of the empires’ relative exclusion from the transatlantic slave trade, owing to the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas. The Spanish empire thereby controlled a series of asiento contracts, whereby the chosen operators were granted exclusive legitimate rights to deliver enslaved persons to the Spanish American colonies.[7] Britain acquired the asiento through the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht and thereafter established the South Sea Company and a sprawling network of ‘factories’ in Cartagena, Panama, Buenos Aires, Portobello, Havana, Veracruz and Caracas, all of which aided in the Company’s domination of the trade.[8] This infrastructure encouraged consistent trade and ensured that Jamaica, from where the Company transhipped the greatest proportion of enslaved persons, became a hub of the inter-imperial slave trade to Spanish America. In excess of 45,000 enslaved persons were purchased in Jamaica and delivered to Spanish colonies during the asiento contract, with the South Sea Company listed as the vessel owner for over 38,000 of these voyages.[9] Britain held the asiento until 1739, when it lost the contract following the outbreak of the War of Jenkins Ear.

Throughout the late seventeenth century, Dutch Curaçao dominated the inter-imperial slave trade to Spanish America. Between 1660 and 1730, Spanish American mainland and Caribbean colonies imported 30,086 enslaved persons from Curaçao. Portobello was the greatest recipient of transshipments from Curaçao, followed by Cartagena, La Guairá and Veracruz. Lesser trade occurred with the Spanish Caribbean colonies of Hispaniola, Cuba, Puerto Rico and Providence Island.[10] During this period, Jamaican merchants operated illicit networks of slave-trading in competition with the asiento, which moved between various European powers including the Dutch and Portuguese. Spanish merchants were encouraged to conduct slave-trading in Jamaica, by shipping costs which were 20% lower than those from Curaçao.[11] The formation of this illicit infrastructure was aided by a shared history of plunder and privateering between Jamaica and the Spanish colonies. When Jamaica came to dominate the trade following 1713, the greatest number of enslaved persons continued to be transhipped to Portobello and Cartagena, while in excess of 3,700 enslaved persons were transhipped to Cuba.[12]

The intra-American slave trade was subject to fluctuations as a result of Atlantic warfare. During King William’s War (1689-1698) and Queen Anne’s War (1702-1713), high shipping costs and the threat of enemy presence in surrounding waters discouraged trade and resulted in an overall decline in slave transshipments. During the British operation of the asiento, Anglo-Spanish tensions near-halted trade between 1719 and 1722, with the issue repeating in 1727 and trade failing to resume until 1729.[13] The Slave Voyages Database highlights that resultantly, Jamaican slave transshipments to British North American colonies including Virginia and the Carolinas rose, as Jamaican colonists temporarily diverted to intra-colonial markets. During these periods, petitions from Jamaican colonists surfaced to reveal Spanish plundering of material goods and enslaved persons.[14] Evidently, Atlantic warfare and European tensions had a significant effect on the patterns of the intra-American slave trade.

The intra-American slave trade operated as an instrument of subjection across the early-modern Atlantic sphere. While intra-colonial and inter-imperial slave-trading became a source of great power and wealth for families such as the Beckfords in Jamaica, who built such an influence that William Beckford went on to serve as Lord Mayor of London in the late eighteenth century, it was at the expense of the enslaved persons whom they exploited.[15] In total, the Slave Voyages Database records nearly half a million enslaved persons routed through intra-American markets between 1514 and 1866, in addition to nearly 10 million enslaved Africans subjected to the transatlantic passage.[16] It is crucial to recognise the role played by intra-American slave-trading hubs including Barbados, Jamaica and Curaçao to understand how this trade perpetuated the commodification of enslaved individuals.

Author’s Bio:

Jennifer is a recent History graduate from the University of Strathclyde. Her dissertation was a comparative analysis of Barbados and Jamaica as hubs of the intra-American slave trade, and she recently completed a research internship investigating Scottish participation in the Danish West Indies. Her interests include early modern Atlantic history and Scots in the West Indies. She is pursuing MSc Historical Studies at the University of Strathclyde in the 2021/22 academic year.

Twitter handle: jennifergrayf

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Colonial State Papers. Minutes of Council of Barbados, June 2, 1685.

CSP. Minutes of Council of Barbados, August 3, 1686.

CSP. Minutes of Council of Barbados, July 12, 1687.

CSP. Journal of Assembly of Barbados, February 19, 1689.

CSP. Petition of the Merchants of London and other trading to and interested in the British Colonies in America, 1726.

Intra-American Slave Trade Database. 2019. Voyages: The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database (consulted 19 August 2021).

Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database. 2019. Voyages: The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database (consulted 19 August 2021).

Secondary Sources

Blackmore, S., ‘The Wealth of the Beckfords’ in C. Dakers, Fonthill Recovered: A Cultural History (London, UCL Press, 2018)

Koot, C.J., Empire at the Periphery: British Colonists, Anglo-Dutch Trade, and the Development of the British Atlantic, 1621-1713 (New York, New York University Press, 2011)

O’Malley, G.E., Final Passages: The Intercolonial Slave Trade of British America, 1619-1807 (Virginia, University of North Carolina Press, 2014)

O’Malley, G.E. & Borucki, A., ‘Patterns in the Intercolonial Slave Trade Across the America’s before the Nineteenth Century’, Tempo, 23:2 (2017), pp.314-339

Palmer, C., ‘The Company Trade and the Numerical Distribution of Slaves to Spanish America, 1703-1739’ in Lovejoy, P.E., (eds) Africans in Bondage: Studies in Slavery and the Slave Trade (Madison, University of Wisconsin, 1986)

Sheridan, R., Sugar and Slavery: An Economic History of the British West Indies, 1623-1775 (Barbados, Caribbean Universities Press, 1974)

Weindl, A., ‘The Asiento de Negros and International Law’, Journal of the History of International Law, 10:2 (2008), pp.229-257

Zahedieh, N., ‘Trade, Plunder and Economic Development in Early English Jamaica, 1655-89’, Economic History Review, 39:2 (1986), pp.205-222

Endnotes

[1] Intra-American Slave Trade Database. 2019. Voyages: The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database (consulted 16 August 2021).

[2] G.E. O’Malley, Final Passages: The Intercolonial Slave Trade of British America, 1619-1807 (Virginia, University of North Carolina Press, 2014), p.7

[3] Intra-American Slave Trade Database. 2019. Voyages: The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database (consulted 16 August 2021). North Carolina and South Carolina from 1712.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid

[6] Ibid

[7] A. Weindl, ‘The Asiento de Negros and International Law’, Journal of the History of International Law, 10:2 (2008), p.229.

[8] C. Palmer, ‘The Company Trade and the Numerical Distribution of Slaves to Spanish America, 1703-1739’ in P.E. Lovejoy (eds) Africans in Bondage: Studies in Slavery and the Slave Trade (Madison, University of Wisconsin, 1986), p. 28

[9] Intra-American Slave Trade Database. 2019. Voyages: The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database (consulted 19 August 2021).

[10] Ibid

[11] N. Zahedieh, ‘Trade, Plunder and Economic Development in Early English Jamaica, 1655-89’, Economic History Review, 39:2 (1986), p.216

[12] Intra-American Slave Trade Database. 2019. Voyages: The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database (consulted 19 August 2021).

[13] Ibid.

[14] Colonial State Papers. Petition of the Merchants of London and other trading to and interested in the British Colonies in America, 1726.

[15] S. Blackmore, ‘The Wealth of the Beckfords’ in C. Dakers, Fonthill Recovered: A Cultural History (London, UCL Press, 2018), p.243. CSP. Minutes of Council of Barbados, June 2, 1685. CSP. Minutes of Council of Barbados, August 3, 1686. CSP. Minutes of Council of Barbados, July 12, 1687. CSP. Journal of Assembly of Barbados, February 19, 1689.

[16] Intra-American Slave Trade Database. 2019. Voyages: The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database (consulted 19 August 2021). Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database. 2019. Voyages: The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database (consulted 19 August 2021).

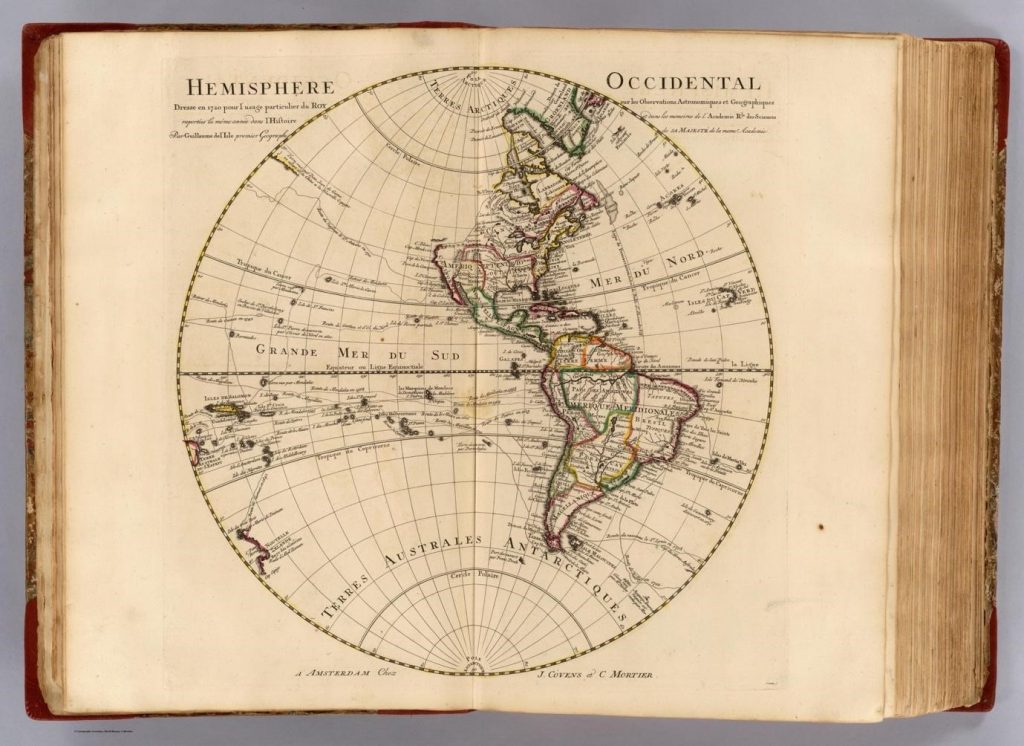

Feature Image: ‘Hemisphere Occidental’ by Guillaume de L’Isle, 1720. Image credit: David Rumsey Map Collection, David Rumsey Map Center, Stanford Libraries.